Claiming Mount Tahoma Steffen Minner HIST400: U.S. History Thesis Seminar

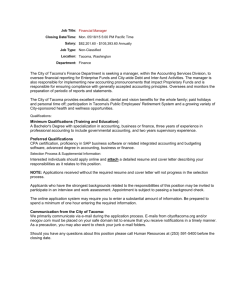

advertisement