The Local Work of Scottish MPs and MSPs:

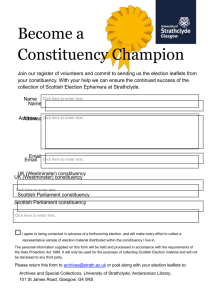

advertisement