Time for a New Convention: Parliamentary Scrutiny of Constitutional Bills 1997–2005

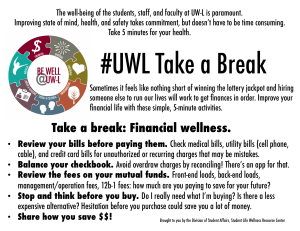

advertisement