WORKING PAPER NO. 17 Intergenerational Poverty and Disability:

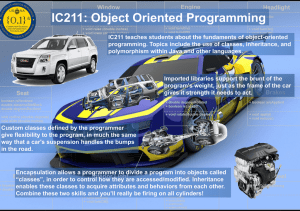

advertisement

WORKING PAPER NO. 17 Intergenerational Poverty and Disability: The implications of inheritance policy and practice on persons with disabilities in the developing world By Dr Nora Ellen Groce, Jillian London and Dr Michael Ashley Stein Intergenerational Poverty and Disability: The implications of inheritance policy and practice on persons with disabilities in the developing world. Working Paper Series: No. 17 Nora Ellen Groce, PhD Leonard Cheshire Disablity and Inclusive Development Centre, Univeristy College London nora.groce@ucl.ac.uk Jillian London, MSc Havard Law School Michael Ashley Stein, J.D, PhD Harvard Law Project on Disability, Harvard Law School Full Working Paper Series http://www.ucl.ac.uk/lc-ccr/centrepublications/workingpapers Cover photo © Leonard Cheshire Disability/Fran Black ABSTRACT The estimated one billion people who live with disabilities (15% of the world’s population) are among the poorest and most marginalized of all the world’s peoples. Over the past decade, a growing body of research has begun to examine the feedback loop between poverty and disability to better understand where interventions can most effectively be made to break the links between poverty and disability. In this paper, we examine the existing data and discuss the implications of current inheritance policies and practises that affect the lives of persons with disabilities and their families, arguing that when persons with disabilities are routinely denied equal rights to inherit wealth or property, this denial has a profound impact on their ability to provide for themselves and their families. The stigma, prejudice and social isolation faced by persons with disabilities and the widespread lack of education, social support networks, and the right to appeal injustices at the family, community or national level, further limits the ability of persons with disability to contest inequities encountered in inheritance policies and practices. This denial of equality in inheritance has profound implications for intergenerational poverty among persons with disabilities. Inheritance has increasingly attracted the attention of researchers and policy makers working on intergenerational and multidimensional aspects of global poverty. However, until now persons with disabilities have been overlooked in discussions of poverty and inheritance. This phenomenon can no longer be overlooked if significant progress is to be made in bringing persons with disabilities into the development mainstream. 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We gratefully acknowledge funding from the UK Department for International Development (DFID) through the Cross-Cutting Disability Research Programme to the Leonard Cheshire Disability and Inclusive Development Centre, University College London. We also thank Dr (Michael) Miles for his assistance in identifying additional historic references on inheritance and disability. 2 CONTENTS Abstract ........................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements ......................................................................................... 2 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 4 Methodology .................................................................................................... 8 Results ............................................................................................................ 9 Discussion ..................................................................................................... 33 Conclusions and Recommendations ............................................................. 36 References .................................................................................................... 41 3 INTRODUCTION Over the past decade, a small but growing body of literature has begun to examine the links between poverty and disability in order to better understand how such ties can be broken and where interventions can be most effectively implemented to improve the lives of disabled persons and their families (Yeo 2001, Parnes 2009, Trani et al 2010)1. Disabled men and women in many countries face stigma, prejudice and social isolation, while lacking the education, social support networks, and legal right to appeal injustices at the family, community or national level (DFID 2000; Lang et al 2011). Issues such as social inclusion and equity, access to education, job training and employment, micro-credit and social support systems have all been examined as important components in breaking cycles of poverty among persons with disabilities (Elwan 1999, Yeo 2001, Braithwaite and Mont 2010). These research efforts are beginning to show that the issue of poverty among persons with disabilities and households with disabled members may be more complex and nuanced than originally thought, and that interventions to alleviate poverty among persons with disabilities must consider barriers to full inclusion at 1 We define disability in line with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which states, “Persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.” We recognize that not all articles cited in this review use the same definition; we believe that this definition is broad enough to encompass most people with disabilities about whom this discussion of inheritance is intended to relate. 4 structural levels far beyond that of the individual and the community (Barron and Ncube 2011; Groce et al 2011). Yet one significant emergent area of concern in global poverty and economic development that is as yet wholly unexplored as it relates to persons with disabilities is the link between inheritance and poverty. Recent advances in legislation, including the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), guarantee equal rights to social and legal protection for persons with disabilities worldwide (UN, 2006). This includes the equal right to own or inherit property cited specifically in Article 12 of the Convention. Despite such advances, in this working paper, we will argue that millions of persons with disabilities in countries around the world continue to face discrimination in inheritance practices, and that this has profound implications for intergenerational poverty, particularly for persons with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries. Such discriminatory inheritance practices continue to occur because many local practitioners within formal legal systems — lawyers and judges — are unaware of or uninterested in the legal changes underway regarding disability, and because customary/traditional legal systems and practices limit the right of persons with disabilities to inherit property, the ability to hold on to property that they do inherit, or the right to appeal decisions made by other members of their families and communities regarding division of property over time. 5 Although a developed body of research on inheritance and disability has yet to be established, anecdotes regarding the denial within families or through the courts of the right of persons with disabilities to inherit land, property or money, or to decide for themselves how to dispose of such wealth as they do inherit, are common. For those persons with disabilities who already live in poverty, who are less likely to marry or receive an education, who face discrimination in job training and employment, and who are socially isolated, the inability to inherit property is often a final blow, moving many from poverty to destitution. These anecdotes reflect a number of issues.2 The account of one 38 year old disabled Nigerian woman reflects the fate of many. Disabled by polio as a child, this woman worked side by side with her non-disabled husband for 18 years to build up a small business, where they sold tobacco, bananas and lottery tickets. Within a week of her husband’s death, his brother, with the backing of the man’s own parents, had taken the shop over and thrown her and her three children out on the streets, commenting that his brother should not have ‘married a cripple’ in the first place. In Tanzania, it was a deaf son who found that while he and each of his six brothers and sisters had been left 1/16th of an acre by his father, his siblings had decided that he ‘did not need’ the land because he ‘could beg to earn the same amount of money.’ A 2 The following anecdotes are taken from field observations and/or results from qualitative research projects undertaken by the authors (NG & MS). 6 farmer all his life, he now lives on the streets of Dar es Salaam, far from the rural community he grew up with, washing cars and asking for handouts. Of note, almost no research has been pursued regarding inheritance rights as these relate to persons with disabilities, particularly in low and middle income countries. It is an issue almost wholly unaddressed in the disability studies literature, it has been largely overlooked in the development literature that is now tackling issues of women and inheritance, and a search of the social justice literature reveals a comparable lack of attention. To address this gap in research this article provides an initial review of what know is currently known about inheritance and disability. Based on a critical review of the legal, social science and development literatures relating to inheritance, poverty, and disability in the developing world, we here examine inheritance and poverty in the context of disability and discuss why further study into this realm is an important—and currently missing component—in efforts to address the devastating effects of poverty on persons with disabilities worldwide.3 3 Because of time constraints we have limited this inquiry to low- and middle income countries, but we note that many of the issues raised here are also relevant to issues of equity and poverty among persons with disabilities in developed countries as well. 7 METHODOLOGY This study began with a desk review of existing evidence relating to inheritance and disability and a review of the existing literature that addresses links between poverty and inheritance. The following social science, international development and legal databases were searched: Abstracts in Anthropology Google Scholar EconLit Family & Society Studies IBBS Index of Foreign Legal Periodicals JSTOR JSTOR Anthropology Legal Journals Index PubMed PsychInfo SSCI Web of Science Women’s Studies International Combinations of the terms ‘disabled persons’, ‘disability’, ‘handicap’, ‘inheritance’, ‘comparative inheritance’, ‘succession’, ‘poverty’, ‘customary law’, and ‘discrimination’ were used. Since we are interested in multiple ways in which property and assets are transferred between individuals, our search also included the terms ‘dowry’ and ‘bridewealth’. Noting that disability and development efforts have recently begun to discuss some of the same issues as these relate to women and development, the terms ‘gender’ and ‘women’ was also used in our searches. Additionally, all major disability journals were searched for the term ‘inheritance’; a general Google search of disability and inheritance was conducted, and Nexis UK was reviewed for any newspaper articles relating to the topic and websites, 8 magazines, newsletters and case law, was also reviewed for any mention of inheritance as it related to adults or children with disabilities. Because we are looking at disability and poverty issues in low- and middle-income countries, we did not review the literature on disability and inheritance in the developed world, although we acknowledge that this is an arena of significance that warrants further study and we hope to return to this issue in future work, however we should note here that there was also little in the literature that pertained to this subject in developed countries. RESULTS Development as it relates to Disability and Poverty The close links and feedback loops as these relate to disability and poverty have been discussed by numerous authors (Elwan,1999; Zimmer 2008; Parnes et al., 2009, Mitra et al., 2011). Many components of this links are now well known. Lack of access to clean water, basic sanitation, nutritious food, health care and education all disproportionately impact the poor and can result in disability (DFID 2000, Parnes 2009). An individual who is born with or who becomes disabled is more likely to be poor, not because of their disability but rather because that individual faces social marginalization and has significantly less chance of accessing health care, education or employment, which leads to poverty and makes it difficult for that individual to work his or her way out of poverty (Mitra et al., 2009, Parnes 9 2009, Trani & Loeb 2012, World Bank 2007). Additionally, households with disabled individuals are more likely than households without disabled members to have lower incomes, fewer possessions, less access to information, lower housing standards, and greater expenses (Eide et al., 2003a, Eide et al., 2003b, Eide & Loeb 2006, Eide & Kamaleri 2006, Loeb & Eide 2004). All of this can lead to poverty, which in turn results in restricted access to safe housing, food, health care and other key development components that leads to further ill-health and poverty (Trani et al., 2010; Groce et al., 2011). This poverty and entrenched social exclusion affects not only the individual, but also the household and often extended family as a whole. The strong links between disability and poverty are of particular note because of the estimated size of the global disability population—according to the recently released World Disability Report, over one billion people worldwide (15% of the global population) live with disability (World Health Organization, 2011). Even in communities where overall poverty unemployment rates are low and poverty rates for persons with disabilities are consistently higher than for all other vulnerable populations in the surrounding community (Elwan 1999, DFID 2000, Barron and Ncube 2010, UN Enable 2011). One in every four households has a member with a disability, 90% of all disabled children still do not attend school and unemployment rates for adults with disabilities are often above 80%. The links between poverty and disability are addressed throughout the new UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN, 2006). In the Preamble, as well as in Articles 28 and 38 the equal inclusion of persons with 10 disabilities in all development and global health efforts is established as a ‘right’. The Convention in turn, has led to a series of new initiatives within the UN system to incorporate people with disabilities into all current and future Millennium Development Goal (MDGs) efforts (United Nations 2011). This focus on poverty reduction is a foundational goal of the new WHO Guidelines on Community-Based Rehabilitation (WHO, 2010) and has served to move efforts forward on the broader inclusion of persons with disabilities in development activities in major UN agencies such as the World Bank, UNICEF and UNDP. Bilateral and multilateral donor agencies are also beginning to recognise the necessity of addressing disability issues in efforts aimed at significantly reducing poverty levels and improving health (DFID, 2000, 2007; Thomas, 2005), both in inclusive general outreach efforts, or in disability-specific initiatives, many of which are linked either implicitly or explicitly to poverty alleviation efforts or public health initiatives (for example, in the US Agency for International Development (US AID), Australia (AusAid), DFID, Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA, 2006), Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA), and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GTZ, 2006). Despite this growing body of research and practice on disability and poverty, strikingly little attention has been directed to the nature of transgenerational poverty and disability, nor to the manner in which distribution of and access to family and household assets affects individuals with disabilities over the course of the lifecycle. This lack of attention is perhaps 11 understandable: it is only in recent years that focus on how inheritance practices among the poor affects individuals has begun to be part of the global discourse on poverty and development, and there is still much that is largely unknown or poorly understood within this area.(Cooper 2010a). Inheritance Before discussing the link between inheritance, poverty, and disability, it is important to have a general understanding of the major features of inheritance practices worldwide and to discuss how these relate to poverty at the individual and household level. Inheritance is a critical means of transferring wealth from one generation to the next. It has been broadly characterized to include the transfer of property and/or other assets from one’s ancestors at various moments in the lifecycle, including birth, death, marriage (often involving dowry or bridewealth), and retirement from work (Cooper, 2010a). A society’s kinship organization, its social structure, and its ideas about freedom, wealth, and equality are all reflected in its inheritance patterns (La Ferrara, 2007; Cooper, 2010a; Doss et al., 2011; Hacker, 2010). Thus, inheritance is not only an economic issue but also a social justice issue. Inequity in the distribution of inheritance often reflects existing inequities within the society, leaving those denied an equal inheritance not only poorer than other family members or destitute, but also with fewer rights to decision making within the family and the community (Cooper, 2010a). Because of this, inheritance has recently begun to receive significant attention in women and development and gender studies literatures, as women in developing countries often face discriminatory inheritance practices, both under 12 national laws and customary laws (Agarwal, 1994; Cooper, 2010a; Cooper, 2010b; Deere and Doss, 2006; Doss et al., 2011; Hacker, 2010). While much of the literature discussing inheritance and poverty in the developing world is related to women’s rights, the framework provided by the gender and inheritance literature is extremely useful for considering how inheritance affects persons with disabilities. Inheritance regimes vary widely across countries and ethnic groups, and in the developing world often involve the interplay between national law and customary law. Inheritance can be either testate (when there is a will) or intestate (there is no will and property devolves according to a society’s governing inheritance laws). A state can affect inheritance practices by limiting testamentary freedom (the amount of a person’s property that an individual is allowed to devise by will) and through their intestate inheritance laws, which establish who will inherit property in the absence of a will (Deere and Doss, 2006). A state can also affect inheritance practices by determining whether or not to respect the customary laws of an ethnic or tribal community living within its borders. Inheritance regimes are either bilineal, in which property runs along both the male and the female ancestral lines, or unilineal, in which property devolves along either only the male or only the female ancestral line (Nauck, 2010; La Ferrara, 2011; Hacker, 2010; Cooper, 2010a). While much of the developed world has adopted a bilineal inheritance system (including the US 13 and the UK), most of the developing world still maintains a unilineal system of inheritance. There are two unilineal forms: matrilineal and patrilineal. In a matrilineal matrilineal system, property devolves along the mother’s ancestral line so that a a man’s heirs are his sister’s children. In a patrilineal system, property devolves along the male ancestral line, usually to a man’s siblings and/or to his children (ibid.). Whether a community has a patrilineal or matrilineal inheritance system is generally linked to whether their wider kinship system is matrilineal or patrilineal. However, as Cooper notes, inheritance practices do not always perfectly follow a matrilineal or patrilineal pattern, as inheritance decisions are often made as a result of “unique personal relationships” whereby an individual can often give land and other assets to someone close to them who is not within the society’s traditional line of descent (Cooper 2010a). This can be achieved through inter vivos transfers (where an individual transfers property to an heir during his lifetime) or through the creation of a will (although the will is not always followed by surrounding family and community members) (Cooper, 2010a; Nauck, 2010; La Ferrara, 2011; Hacker 2010). Inheritance practices also are often determined in light of religious practices and beliefs. For example, in Hindu inheritance law, which governs most of the population of India and is also present in much of Sub-Saharan Africa, two schools of law exist. Under the Dayabhaga School, a man is free to will all of his property as he pleases. Under the Mitakshara School, however, a man’s property is divided into personal property and joint ancestral property (often referred to as “coparceny”). While a man may will his personal property as he sees fit, he is not allowed to will joint ancestral property, which belongs equally to himself and his sons at birth. 14 Furthermore, daughters are not allowed to inherit ancestral property (Sivaramayya, 1997). While the Hindu Succession Act of 1956 gives daughters and sons in India equal inheritance rights to personal property, it did not affect the distribution of ancestral property. Consequently, there is still an unequal inheritance between sons and daughters in Mitakshara Hindu Law (Carroll, 1991). Under Islamic inheritance law, which governs inheritance practices in modern Muslim states as well as in much of India and among many tribes in Sub-Saharan Africa, only one-third of an estate can generally be willed freely, with the remainder being divided between the deceased’s children and other required heirs (Deere and Doss, 2006). Furthermore, daughters are entitled to only one-half the share of sons and widows are entitled to only half of what widowers receive (Hacker, 2010). Worldwide, there exists a wide variety of inheritance regimes and practices that affect what property can be distributed and to whom that property can be distributed. These practices often involve the interplay of various religious, state, community and family laws and traditions, as well as personal preferences and decisions. Any study of inheritance in the developing world must therefore keep in mind the complexity of inheritance systems as well as the multitude of actors involved in the distribution of an individual’s wealth to the next generation. Inheritance and Poverty In her recent important review of the relationship between inheritance and the inter-generational transmission of poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa, 15 Cooper notes that “inheritance is a major means for the transfer, or exclusion from the transfer, of adults’ accumulated physical capital. As such, it can have positive or negative effects on different people’s poverty statuses over the life course. Inheritance events can either be boons of property accumulation or they can strip people of their previous security of access to assets.” (Cooper, 2010a). The link between inheritance and poverty has received growing attention within the development literature, particularly in relation to how a lack of inheritance rights affects women (Bird, 2007; Cooper, 2010a; Cooper, 2010b; Deere and Doss, 2006; Doss et al, 2011; Agarwal, 1994). The new attention to inheritance reflects the realisation that inheritance can provide the younger generation with the economic means for an independent livelihood. Control over assets can increase an individual’s productive capacity and help individuals move out of poverty (Doss et al., 2011). Conversely, recent studies in Sub-Saharan Africa have shown that a lack of inheritance “exacerbates vulnerability” to chronic poverty and to inter-generational poverty transmission (Cooper, 2010a). Those who are denied inheritance, even where only small amounts of property or cash are involved, may face destitution. There are several key reasons why this is so. For one thing, in the developing world inheritance is often one of the only means that one has of obtaining property and other economic assets. Furthermore, the right to dispose of property or land gives an individual a continuing voice in family and community matters even when ill or elderly. ‘Property’ in this sense can be quite limited, for instance, the bicycle, sewing machine or cook stove needed to continue to be self-employed. 16 In addition, even if one is able to obtain money and other non-land assets through alternative means, inheritance is often the major (or only) method of obtaining rights to land (Agarwal, 1994; Cooper, 2010a). Land has long been viewed as having singular importance in developing economies. In addition to providing a means for “food, shelter and economic activities” and to being a “primary source of wealth, social status, and power”, land gives one access to other important resources critical to survival, such as water rights, sanitation and electricity (Cooper, 2010a). Agarwal notes that “[i]n the agrarian economies of South Asia…arable land is the most valued form of property, for its economic, political and symbolic significance” (Agarwal, 1994). Control over land allows one to be self-sustaining, to obtain further wealth through crop production, and to sell or lease all or part of the land in times of economic need. It can also provide an individual with a sense of identity, belonging, status, and the right to have a political voice within their community. Furthermore, land is viewed by many in South Asia as having a “durability and permanence which no other asset possesses” (Agarwal, 1994). In the gender literature, there is evidence that increased access to land has improved women’s welfare, productivity, equality and empowerment (Agarwal, 1994). There is reason to believe that access to land would have a similar effect on persons with disabilities. If inheritance is one of the only means of obtaining land, it is thus crucial to ensure that persons with disabilities are guaranteed inheritance rights so that they too can gain access to and rights 17 over land, in addition to being able to inherit money and other physical assets that will contribute to their overall level of wealth and well-being. It should also be noted that while recent research has considered how the reform of inheritance laws and practices could improve people’s abilities to escape poverty, there is a “significant gap in empirical data concerning how inheritance systems work to prevent, escape or exacerbate individuals’ and households’ poverty” (Cooper, 2010a). Thus, more research is clearly needed in this area. Inheritance as it Related to People with Disabilities Given the preceding discussion of the link between inheritance and poverty, it is next important to delineate the connection between persons with disabilities and inheritance rights. Here, the lack of attention to the subject, either in theory or practice, is striking. In our desk study, more than 90 publications in 60 journals, books, websites, and newspapers were identified for initial review based on some attention to various aspects of inheritance, poverty and/or disability. Of these publications, approximately 40 were selected for more in-depth review based on a reading of their abstracts and introductions. Notably, we were unable to identify a single study in any of the literatures that focuses exclusively or specifically on inheritance rights and persons with disabilities in the developing world. However, we were able to identify enough references in the literature to conclude that persons with disabilities are often denied the same inheritance rights enjoyed by non-disabled individuals. It should also be noted that where mention is made in the literature on disability and inheritance practices, almost all examples are given as passing mention, with the 18 authors simply stating that persons with disabilities are denied inheritance rights, without providing full explanation or evidence for this assertion. Notably, the exclusion of persons with disabilities from inheritance appears to have taken place throughout recorded history. Miles (2002) finds that disability, property and inheritance mentioned in relation to one another in a number of Asian texts. For example, in Al-Marghinani’s 12th century scholarly commentary on Islam called the Hedaya, still used among South Asian Muslims, it is noted that in the Qur’an, (Surah 4, verses 5-6), intellectually disabled persons are prescribed guardianship and are not allowed to maintain control over their own property because this would go against their best interests (Al-Marghinani, 1975). Not all ancient Islamic scholars agreed with these prohibitions, however. For example, the legal scholar Abu Hanifa advocated for the withholding of the property of the person with intellectual disabilities only until the age of 25, after which age, a person should be given his property regardless of his capacity as denying property after this point would be inhumane and would outweigh the risk of allowing the intellectually disabled person to control his property. Ancient Hindu Law texts also mention property and inheritance rights of disabled persons. Disabled persons were discussed as being excluded from inheritance in the Mitakshara from the 11th century CE (Miles, 1999). In addition, Miles lists several Hindu law books where disability and inheritance were mentioned in various web bibliographies (Miles, 2008). For example, in 19 the Minor Law Books, Narada from around the 4th/5th century CE notes the exclusion of disabled persons from inheritance but also asserts that they must be maintained and that their sons must be allowed to remain inheritors (Jolly, 1989). Similar provisions calling for the exclusion of disabled persons from inheritance but the requirement that they be maintained by others and/or that their sons be allowed to inherit are found in other texts (see for example: Institutes of Vishnu, XV: 28-34 (Jolly, 1880); MANU, IX: 201-202 (Hopkins, 1995); Guatama, XXVIII: 43-44 from the Sacred Laws of the Aryas (Bühler, 1897); and Baudhayana, I.2.3 and I.2.4 from Sacred Laws of the Aryas, Part II (Bühler, 1882)). Interestingly, Miles (2008) also notes in his bibliographies that Part II of the Pahlavi Texts from ancient Persia, (Ch. LXII: 4) asserts that a son or his wife “who is blind in both eyes, or crippled in both feet, or maimed in both his hands” is entitled to twice the share of a non-disabled son (Müller, 1882). Two articles on historic practices are of particular interest. Metzler, exploring the history of disability in the Middle Ages, notes that the exclusion of “impaired people” from rights of inheritance originates from Roman law and that this practice was adopted in the Middle Ages. For example, in the law book containing the legal code from Germany in the Middle Ages, called the Sachsenspiegel, “people born ‘dumb, blind, or lacking hand or foot’ were not allowed to inherit property according to feudal law (Lehnsrecht) but could do so under territorial law (Landrecht)” (Metzler, 2011). Groce (1985) cites additional examples of denial of the rights of inheritance or primogenitor for deaf persons in Medieval Europe. Buckingham, in her study on the history of disability in India, notes that in pre-modern India persons with disabilities 20 were denied inheritance in the higher levels of Hindu caste society. Buckingham discusses a dharmasastric text from the 4th century AD that listed ‘a madman, an idiot, one born blind, and he, who is afflicted by an incurable disease’ as people who were rendered unable to inherit” due to the fact that they were thought to lack the capacity to perform required family rituals (Buckingham, 2011). A further handful of recent articles in the development literature and in the disability literature mention the current exclusion of persons with disabilities from inheritance in the developing world when listing reasons for the links between disability and poverty. For example, Zelina Sultana notes in her study of disability and the Bangladesh legal system that Bangladeshi inheritance law discriminates against persons with disabilities (Sultana, 2010). In particular, the Lunacy Act 1912, which is still enforced, allows persons with intellectual or mental disabilities to be declared incapable of managing their property interest; thus, Muslim families governed by this law often keep individuals with these disabilities from claiming their genuine share of the family property. Furthermore, while the Hindu Inheritance (Removal of Disabilities) Act 1928, which is also in force in Bangladesh, states that while no person governed by Hindu Law who suffers from any disease, deformity, or physical or mental defect may be excluded from inheritance or any other share in joint family property, this requirement does not cover a person born “a lunatic or idiot” (Sultana, 2010). Another example comes from the work of Rebecca Yeo who, in her study on the relationship between chronic poverty 21 and disability in the developing world, asserts that in many low-income countries persons with disabilities are low priority for, or are entirely excluded from inheritance by, their families (Yeo, 2001). More specifically, Charles Lwanga-Ntale and Kate Bird et al. (citing Lwanga-Ntale) note that in Uganda, customary law prohibits persons with disabilities from inheriting land (Lwanga-Ntale, 2003; Bird et al. 2004). Lwanga-Ntale quotes a group of disabled women in Uganda who told her “that a disabled person cannot inherit land. A brother’s child may even be preferred in inheritance if he is not disabled.” The degree of exclusion from inheritance may depend not simply on the presence or absence of disability but on the specific type of disability an individual has, and on the social and cultural perceptions held about that specific type of disability. Persons with intellectual or mental health disabilities may face greater exclusion because they may be considered incapable of looking after property themselves. This may be particularly relevant in the case of, for example, Hindu Law, which places significant importance on joint ancestral property that belongs to multiple family members, and also in many Sub-Saharan African societies where property is considered communal. Since the family or community is likely to be concerned with losing their joint estate, they may not trust a person with an intellectual or mental health disability to look after the property interests of the family or community. As Yeo notes, “Where there are limited resources it may be seen as economically irresponsible to give an equal share of resources to a disabled child who is perceived as unlikely to be able to provide for the family in the future” (Yeo, 2001). 22 Communal inheritance may not be the only issue. For example, a deaf individual may be unable to communicate his ability to look after the property and is likely to be unable to access the court system to challenge those who deny him his inheritance rights, as few courts in developing countries provide a sign language interpreter and poor deaf individuals are often unable to afford to hire interpreters themselves (Groce and Keatley 2012). Although no literature discussing the variation in inheritance rights for persons with different types of disabilities was identified in this desk study, this is an area for future research. The double discrimination faced by women with disabilities is another area for further exploration. Women with disabilities face stigma and discrimination on account of both their gender and their disability and “unlike other women, [women with disabilities] have little chance to enter a marriage or inherit property that can offer a form of economic security” (Parnes et al., 2009). In Nepal, society in which marriage is the norm, 80% of disabled women do not marry (Dhungana, 2006) and while disabled men have property rights, disabled women do not. Furthermore, given that women in Nepal (disabled or not) are completely denied the right to inherit property on an equal footing with men, the fact that women with disabilities are often denied the opportunity to marry leaves them without any access to property rights even through their husband (Dhungana, 2006). (This speaks to a wider literature on women and disability with respect to marriage which we will return to below). 23 Finally, it is important to note that traditional inheritance practices vary widely. The evidence does not support the conclusion that all communities in all developing countries follow discriminatory inheritance practices towards persons with disabilities. Aud Talle in her study on disability among the Kenya Massai, for example, notes that the Massai moral code requires that disabled children be given equal treatment to non-disabled children, including in marriage and in the inheritance of their parents’ livestock (Talle, 1995). Given the lack of research into inheritance and disability among ethnic and tribal communities, it may be the case that other groups share similar ideas about the equal rights of persons with disabilities although this has yet to be noted in the literature. Disability and the Practices of Dowry and Bridewealth Another form of “inheritance” that is important to consider in relation to persons with disabilities is the inheritance that occurs during the marriage process. In many societies, marriage presents one of the major moments in life in which the transfer of wealth from one generation to the next occurs. There are two major forms of marriage related wealth transfer: dowry and bridewealth. Dowry is more prevalent in Asian societies while bridewealth is common in much of Sub-Saharan Africa. In the case of a dowry, property, money and/or other assets are given by the bride’s family to the groom or his family. In the case of bridewealth, property, money and/or other assets are given by the groom or his family to the bride’s family (Cooper, 2010a). 24 In many cases, dowry is the only inheritance a woman will receive, as she is denied the opportunity to inherit land and other assets from her family through customary or formal law (Schlegel and Eloul, 1988; Carroll, 1991). In other cases, dowry might form part of a woman’s inheritance, as she will still receive her entitled share in the family’s wealth at the death of her father and/or mother (Schlegel and Eloul, 1988). Some of the literature considers dowry in particular to be a form of pre-mortem inheritance (Goody, 1976; Nauck, 2010). Significantly however, although many disabled adults do have relationships, stigma, prejudice and customary laws in many countries mean that they are less likely to formalize these relationships through marriage. The result is that both men and women with disabilities, (but particularly women with disabilities), will often live in relationships for years without the benefit of marriage (WHO/UNFPA, 2009). This lack of formal marriage, already identified as an issue in the links between poverty and disability (Elwan, 1999; Yeo, 2001; Groce et al., 2011), also has profound implications for inheritance, including the right to inheritance of property or resources generated over the course of the relationship. Even marriage does not ensure equitable treatment for persons with disabilities. In societies where dowry or bridewealth is practiced, disabled individuals or their families will often be required to pay a higher dowry or bridewealth in order to obtain a marriage partner. In her discussion of 25 disabled women and the women’s and disability movements in India, Anita Ghai explains that, because marriage involves the gifting of the virgin by her father to the groom and his family, and because it is anticipated that that gift will be “perfect”, the family of a disabled girl in India must often pay a higher dowry in order to compensate for the daughter’s so-called imperfections (Ghai, 2002). Both Nilika Mehrotra in her study of disabled women in rural Haryana and Monawar Hosain et al. in their study of disability in Bangladesh report similar findings, noting reports of disabled girls’ families having to pay heavy dowries in order to secure a marriage for their disabled daughters (Mehrotra, 2004; Monowar Hosain et al., 2002). One study of people with physical impairments in Dakar provided evidence of a similar situation in relation to bridewealth, where obtaining a wife for a disabled son required payment of a higher than normal bridewealth (Whyte and Ingstad, 1995), which can take many years to collect. In addition to the barrier presented by the need for higher dowry or bridewealth, another issue raised in the literature reviewed is whether families were generally willing to pay the higher dowry or bridewealth required in order to marry off their disabled children. Over and above the potential inability or unwillingness to pay this higher dowry or bridewealth, it is also important to keep in mind that even if a higher dowry or bridewealth is forthcoming, finding a spouse for a disabled man or woman can be particularly difficult given the stigma and discrimination persons with disabilities face in many countries. 26 Disabled women appear to have a more difficult time than disabled men in obtaining marriage partners, both because of the double stigma of gender and disability, and the concern in many societies that a disabled woman will be unable or less able to fill traditional roles required of wives and daughter-in-laws, including the ability to have and raise healthy children (Habib, 1995; Rahman and Ahmed, 1993). For many disabled women marriages are not an option, but there are other possibilities that await some. For example, in those societies which have polygamous marriage patterns, women with disabilities are more likely to be junior wives with less right to inherit whatever property exists. It is even the case that in some locations disabled women unable to obtain marriage partners for themselves may become “part” of their female family member’s dowry instead. In the course of fieldwork, one author of this paper (NG) was told by a disabled informant that she herself had been ‘given’ as part of her non-disabled sister’s dowry to her sister’s husband’s family, who had in turn, married her to an elderly uncle more than fifty years her senior, so that she could serve as his nurse. In societies where marriage might be the only means for women to obtain access to land and other assets, given their exclusion in post-mortem inheritance, an inability to marry or to be the “first” wife may keep disabled women from obtaining any form of wealth at all. It is also important to keep in mind that often a significant portion or in some societies, all of the dowry will not be received by the bride herself but will instead go to the groom and his family (Tambiah et al., 1989). In such arrangements it is debatable whether 27 dowry should be considered to be a form of inheritance that could assist disabled women in obtaining any independent wealth. Legal Pluralism Another issue that emerged during our review that is likely to have a significant impact on the inheritance rights of persons with disabilities is legal pluralism. Legal pluralism can be defined as “the coexistence and interaction between multiple legal orders such as state, customary, religion, project and local laws, all of which provide bases for claiming property rights” (Meinzen-Dick and Pradhan, 2002). In much of the developing world, there exist overlapping systems of law that govern people’s lives. These systems often contradict and compete with one another. It can be difficult to know which system is in control at the individual and community level, and furthermore, what the law on the books says may not reflect what occurs in practice. This can create significant difficulties when it comes to the laws of inheritance. It is not unusual, for instance, for different parties to appeal to different legal systems in order to assert their claim to inherit the same piece of property (Irianto, 2004). Statutory law recognizes the primacy of customary law when it comes to inheritance in many countries. This can be disadvantageous for women and minority groups whose statutory rights to equality before the law will be undermined by the customary practices of their local communities. Cooper observes that Botswana, Lesotho, Ghana, Kenya, Zambia and Zimbabwe exempt inheritance matters from the 28 gender-based non-discrimination provisions in their national laws (Cooper, 2010a). Irianto, in her study of the interaction between state and customary law in Indonesian inheritance court cases, notes that formal Indonesian regulation makes no mention of women having any title to inheritance (Irianto, 2004). Reliance on customary law throughout Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia often keeps women from inheriting or at least inheriting equally with male family members. Such laws pertain to both intergenerational inheritance (from parents for example) and from spouses. Furthermore, much of customary law is uncodified, flexible, and often changing (Kameri-Mbote, 1995; Bushbeck, 2006). As formal wills are often unknown or ignored in African customary law, inheritance matters will almost always be intestate (Mwenda et al., 2005). These two factors make it relatively easy for family members and chief elders to manipulate customary laws in order to keep or take property from women and other vulnerable individuals. Reviewing African customary laws Cooper (2010a) and Mwenda et al (2005) both note that while national laws in many countries now guarantee equal inheritance rights to all by statute, this does not mean that discriminatory customary law does not still dominate. For example, while Kenya’s new constitution, enacted in 2010, made it illegal to discriminate against women in inheritance matters, many ethnic tribes have ignored the 29 new constitutional provisions and have instead maintained their discriminatory customary practices denying women inheritance rights (Mbatiah, 2010). Additionally, Additionally, property-grabbing by family members is common in much of SubSub-Saharan Africa, and even if property-grabbing is outlawed by the state, family members ignore these laws while those individuals meant to enforce the law may fail to do so as they often directly or indirectly benefit from the property-grabbing themselves (Mwenda et al., 2005). While we already know that property-grabbing is common among widows and orphaned children, numerous anecdotes throughout the disability community and collected during fieldwork (NG nd) makes it evident that disabled persons are routinely victims of property-grabbing and that they also lack the ability to challenge these practices in state courts. Vulnerable individuals may find it extremely difficult to bypass their family, and traditional community leaders in order to assert their rights within the national legal system, both because they are unaware of their legal rights and/or because they fear retaliation or alienation by their family and community if they resort to non-community based legal systems. Even if individuals are aware of statutory laws that protect their inheritance rights, many may choose to go through local leaders and local processes because they are more familiar and less expensive (Cooper, 2010b). These local legal processes may be staffed by a justice who “lack[s] strong legal training and who relies more on conventional wisdom than on rules of evidence and substantive law” (Mwenda et al., 2005). And even if individuals are able to take their cases before a state court, the court may still apply customary law and “take 30 personal relations, specific circumstances and backgrounds…into account, not only strict legal rules” (Bushbeck, 2006). An additional difficulty of statutory law is that it generally does not recognize polygamous marriages, leaving women who are second or third wives without any recourse to inheritance rights through state law at all. As noted above, disabled women are often given as a second or third wife or mistress, meaning that they are at increased risk of being left without recourse to statutory inheritance rights because their position in and contribution to the household is not legally recognized. While most of the discussion in the literature centres around the negative impact of customary law on the inheritance rights of women, similar conclusions can likely be drawn for the impact of customary law on disabled individuals who may be guaranteed the right to an equal inheritance by statutory law but who are denied that inheritance because of the customary laws in place. For example, in those communities where there is strong stigma and prejudice against persons with disabilities or where persons with disabilities are considered objects of charity and protection but not independent adults, decisions made by local leaders or justices who believe they are acting in these individuals’ best interests may have dire implications for these individuals’ economic well being. There may be other barriers as well. There are many reports of women who have attempted to circumvent traditional inheritance systems by 31 appealing to state courts being threatened and beaten for having done so, and many also face alienation from family and community after having questioned inequitable inheritance practices (Agarwal, 1994; Mwenda et al., 2005). Threat of violence and the prospect of alienation might be of increased concern for persons with disabilities who already often face increased risk of violence both within and beyond their families, as well as social isolation and marginalization. Alienation from family and community for those persons with disabilities who are physically or psychologically dependent on family for a number of activities of daily living, may present an additional barrier to their willingness to appeal unfavourable inheritance decisions and practices. One more variation on the links between persons with disability and inheritance is also worth noting. There is almost no mention in the developing world literature – and little in literature from developed countries as well – of cases where issues of inheritance affect decisions to institutionalize disabled relatives or threats of institutionalization are used as leverage to gain compliance when inheritance matters are discussed. Yet anecdotal evidence again indicates that where institutionalization of persons with disabilities continues to be practiced, the links between inheritance and decisions to institutionalize family members deserves further exploration. A further exploration of customary and state law as it relates to inheritance among persons with disabilities is crucial if we are to understand the underlying processes that affect disabled persons’ economic status and the relationships between disability and poverty. 32 DISCUSSION The intergenerational links between disability, inheritance and cycles of poverty deserves greater attention. In the preceding review of available data, we have raised a number of key issues that warrant further investigation. As we have noted, the link between inheritance and poverty has begun to receive attention within the gender and development literature, and many of the issues being raised have specific relevance to known issues within the realm of disability and development. Although the literature establishing a direct link between inheritance, poverty, and disability is currently strikingly thin we can extrapolate from the gender and inheritance literature to anticipate key difficulties disabled persons appear to also confront. On the individual level, disabled persons are significantly less likely to obtain an education and to have broad social networks that allow them the levels of literacy, knowledge and awareness to learn about their inheritance rights. As is the case with many impoverished women, persons with disabilities may feel disempowered to assert their rights because they have grown up facing stigma and discrimination and because they live in poverty and lack the monetary resources to approach a lawyer or appeal to a judge or court. Thus, there is a vicious circle in which disabled persons lack the empowerment, education, resources and access to assert their inheritance rights, while that very inheritance would potentially provide them with the increased empowerment and access that would enable them to become full participants in their families and communities. 33 Additionally, disabled persons face barriers on the community and family level. It is well-established that an individual’s family and community have a significant impact in shaping that individual’s opinions about themselves and their capabilities. Even though the family/community may have the disabled person’s best interests in mind, family and community members may convince persons with disabilities that they lack the ability to adequately maintain property because they truly fear the difficulties their disabled relative might face or they believe that if they control this inheritance they will be better able to provide for their disabled relative as a dependent. Much like the phenomenon of women relinquishing their inheritance rights after being told by their family and community that doing so would be best for all parties involved (Hacker, 2010), it is not unlikely that disabled individuals may similarly relinquish their inheritance rights after facing surrounding pressure, believing that they are best serving themselves and their families and communities by doing so. Situations may also exist in which persons with disabilities relinquish their rights to inheritance to repay relatives, believing they have been a burden and this is a way to ‘repay’ others for their care and concern. Customary legal systems provide additional barriers. As customary law is often flexible and open to manipulation, community members and community leaders may use these systems to enforce discriminatory inheritance practices against persons with disabilities, much as they do against women. Disabled persons’ 34 already weak position within their communities makes it particularly difficult for them to challenge the decisions of their chief, respected elders or local judges. Finally, legal pluralism means that it is often difficult for disabled persons to know which legal system governs their inheritance rights. In addition, legal pluralism makes it relatively easy for families and communities to “forum shop” for a legal system that will most easily allow them to deny disabled persons their inheritance rights. In many states, statutory law excludes customary inheritance practices from their non-discrimination clauses, legitimating discriminatory practices. Even in states that do not create exceptions in their national laws for customary inheritance practices, a lack of enforcement mechanisms means that communities and families often ignore state law. Lawyers and judges themselves may prove an additional structural barrier when it comes to persons with disabilities. Not only might lawyers and judges lack knowledge of the applicable laws that protect the inheritance rights of persons with disabilities at the national and international level, but the general stigma surrounding disabled persons may also be shared by members of the legal profession. Disability issues are rarely the focus of legal training, and there is no reason to anticipate that many lawyers and judges will have any more insight into the lives of persons with disabilities than members of the general public unless they are specifically reached and trained to think differently. Compounding this is the inaccessibility of the court 35 rooms and legal offices themselves. If court rooms or legal offices lack access to sign language interpreters, it may be impossible for deaf persons to utilise them; if they are not wheelchair accessible, it may impossible for wheelchair users to enter them. Finally, persons with disabilities who live in rural communities are at an even greater disadvantage than those who live in cities simply because of the distance to lawyers, judges, and the courts, that would allow them to access the national legal system, making them even more reliant on the local, customary legal mechanisms for inheritance. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS While it can be argued that the new Convention the Rights of Persons with Disabilities will override more traditional legal systems, and that the laws of all countries that have ratified the Convention will be aligned with the Convention, this will not necessarily extend to changes at the individual level. The Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1979 (UN 1979), has been ratified by 187 countries and women still face discrimination in most countries around the world. While it is of note that inheritance rights of persons with disabilities have received some mention in the Convention it has received no other attention any other UN Convention or international treaty to date. As has become more than 36 apparent through this desk review, research into inheritance and disability is strikingly thin and almost entirely conjectural. Perhaps the most important finding from this research, then, is the need to further explore –through field studies, an examination of case law, and discussions with persons with disabilities themselves – the extent to which persons with disabilities are being denied their right to inherit through state, customary, and informal legal practices. The ramification that this denial of inheritance has on poverty for persons with disabilities at the individual and intergenerational level, needs to be more fully understood. More insight into these issues will allow us to better identify where significant changes can be made that will improve the social and economic standing of persons with disabilities. In light of the limited body of evidence currently available, any recommendations made in this paper must be preliminary. There are, however, several interventions that, even at this point, can be identified as likely to improve disabled persons’ access to inheritance, and we offer these here. First, there is a need to advocate for changing the law, both statutory and customary. Those countries that currently exempt inheritance from the non-discrimination clauses of their statutory laws will need to reform their laws to no longer include this exemption to conform to the requirements of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. As most people die 37 intestate (Hacker, 2010), reforming statutory law so that disabled persons are automatically included in the distribution of their family members’ wealth could have have a profound effect on their inheritance prospects. Further, while the reform of reform of customary law is likely to prove difficult given its localised nature and the fact that it is generally uncodified, engagement with local leaders may lead to improvement in customary inheritance practices. While changing the law is an important first step, there is no guarantee that doing so will affect disabled persons’ inheritance rights in practice. Further steps will need to be taken to ensure that inheritance rights codified in law are actually guaranteed and followed at the individual and community level. Education and awareness-raising will thus be an important next step. Disabled persons themselves will need to be educated so that they are aware of their rights, as well as being educated about how to access the legal system in order to effectively assert rights that are being denied to them. Lawyers and judges will also need to be educated about the new laws so that they can help to effectively implement them. Education within local communities will also be crucial, as family, community members and community leaders will need to be made aware of the laws and how they affect their testamentary freedom. Furthermore, monitoring by human rights organizations and disabled persons’ organizations will be necessary to ensure that inheritance rights are being implemented at the community and the national level. In addition, making the law offices and courts more accessible to disabled persons is crucial to ensuring that they can effectively assert their claims to 38 inheritance. Providing sign language interpreters and making courtrooms wheelchair accessible are two examples of how this can be achieved. Furthermore, ensuring that persons with disabilities living in rural communities have access to lawyers is key to improving the inheritance rights of those persons with disabilities who are most vulnerable to having their rights be denied by family or community members. While it is clearly important to ensure that disabled persons are not discriminated against in inheritance, we must recognize the legitimacy of concerns that some families may hold. For instance, a person with an intellectual disability might require support to best determine how to manage money and assets; similarly, a person with a serious mental health problem might need facilitation in order realistically decide how to spend their inheritance. If an individual needs that inheritance for medical or psychological care or support over the course of a lifetime and is unable to make appropriate decisions, allowing them to have atomistic control over their inheritance might lead to potentially devastating consequences. Ways in which disabled persons can still be given equal inheritance rights while taking into account the fact that some persons with disabilities might require help in order to manage their inheritance is an issue requiring careful consideration and discussion within and beyond the disability advocacy community. Additionally, an important consideration in relation to inheritance and disability is the unique situation that families face in determining whether and how to give an inheritance to their disabled children. 39 Finally, disability advocates and DPOs must become involved in and develop an expertise on inheritance and disability both at the policy and practice levels to provide advice, guidance, training and advocacy. The ability of persons with disabilities to inherit is an issue that should be brought to the forefront of the disability and development agenda if the issue of poverty is to be realistically addressed. 40 REFERENCES Agarwal, B. (1994). Gender and Command Over Property: A Critical Gap in Economic Analysis and Policy in South Asia. World Development. 22(10), 1455-1478. Al-Marghinani, (Hamilton, C., trans.) (1975). The Hedaya. 2 nd ed. Lahore: Premier Book. Barron, R; Ncube (2010). Poverty and Disability. T.Barron and JM Ncube (editors). London: Leonard Cheshire Disability and Leonard Cheshire Disability and Inclusive Development Centre, University College London. Bird, K., Pratt, N., O’Neill, T., & Bolt. V. J. (2004). Fracture Points in Social Policies for Chronic Poverty Reduction. Working Paper 47, Chronic Poverty Research Centre. Working Paper 242, Overseas Development Institute. Bird, K. (2007). The Intergenerational Transmission of Poverty: An Overview. Working Paper 99. Overseas Development Institute and Chronic Poverty Research Centre. Braithwaite; J Mont D. (2010) Disability and Poverty: A Survey of World Bank Poverty Assessments and Implications, World Bank SP Discussion Paper No. 0805, Washington, DC: World Bank, p 18, at http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DISABILITY/Resources/2806581172608138489/WBPovertyAssessments.pdf., Accessed July 14 2011. Buckingham, J. (2011). Writing Histories of Disability in India: Strategies of Inclusion. Disability & Society, 26(4), 419-431. Bühler, G., trans. (1897). Sacred Laws of the Aryas, Part I. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Bühler, G., trans. (1882). Sacred Laws of the Aryas, Part II. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Bushbeck, K. (2006). Customary Inheritance Law – Methodological Aspects of Research and Main Features of Inheritance Traditions. In Hinz, M. O., & Patemann H. K., eds., The Shade of New Leaves: Governance in Traditional Authority; a Southern African Perspective. Berlin: Lit Verlag. Carroll, L. (1991). Daughters’ Right of Inheritance in India: A Perspective on the Problem of Dowry. Modern Asian Studies, 25(4), 791-809. 41 Cooper, E. (2010a). Inheritance and the Intergenerational Transmission of Poverty in SubSaharan Africa: Policy Considerations. Working Paper No. 59. Chronic Poverty Research Centre. Cooper, E. (2010b). Women and Inheritance in Five Sub-Saharan African Countries: Opportunities and Challenges for Policy and Practice Change. Paper presented at the conference ‘Ten Years of War Against Poverty’. Deere, C. D., & Doss, C. R. (2006). Gender and the Distribution of Wealth in Developing Countries. Research Paper No. 2006/115. United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research. DFID. (2000). Disability, Poverty, and Development. London: DFID. DFID. (2007). How to Note: Working on Disability in Country Programmes. London: DFID. Dhungana, B. M. (2006). The Lives of Disabled Women in Nepal: Vulnerability Without Support. Disability & Society, 21(2), 133-146. Doss, C., Truong, M., Nabanoga G., & Namaalwa, J. (2011). Women, Marriage, and Asset Inheritance in Uganda. Working Paper No. 184. Chronic Poverty Research Centre. Eide, A. H., Kamaleri, Y. (2009). Living Condition among People with Disabilities in Mozambique: A National Representative Study. SINTEF Health Research. Oslo, Norway.http://www.sintef.no/upload/Helse/Levek%C3%A5r%20og%20tjenester/LC%20Repor t%20 Mozambique%20-%202nd%20revision.pdf. Eide, A. H., Loeb, M. E. (2006). Living Conditions Among People with Activity Limitations in Zambia: A National Representative Study. SINTEF Health Research. Oslo, Norway. http://www.sintef.no/upload/Helse/Levek%C3%A5r%20og%20tjenester/ZambiaLCweb.pdf. Eide, A. H., Nhiwathiwa, J. M., Loeb, M. E. (2003a). Living Conditions Among People with Activity Limitations in Zimbabwe: A Representative Regional Survey. SINTEF Health Research. Oslo, Norway. http://www.safod.org/Images/LCZimbabwe.pdf. 42 Eide, A. H., van Rooy, G., Loeb, M. E. (2003b). Living Conditions Among People with Activity Limitations in Namibia: A Representative National Survey. SINTEF Health Research. Oslo, Norway. http://www.safod.org/Images/LCNamibia.pdf. Elwan, A. (1999). Poverty and disability: A survey of the literature. Social Protection Discussion Paper Series. Washington, DC: World Bank. Ghai, A. (2002). Disabled Women: An Excluded Agenda of Indian Feminism. Hypatia, 17(3), 49-66. Goody, J. (1976). Inheritance, Property and Women: Some Comparative Considerations. In Goody, J., Thirsk, J., & Thompson, E. P., Eds. Family and Inheritance: Rural Society in Western Europe, 1200-1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Groce, N. (1985). Everyone Here Spoke Sign Language: Hereditary Deafness on Martha’s Vineyard. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. Groce, N., Kett, M., Lang, R., Trani, J. F. (2011). Disability and Poverty: The Need for a More Nuanced Understanding of the Implications for Development Policy and Practice. Third World Quarterly. (in press) Groce N, Keatley R. 2012. Non-Signing Deaf in Low and Middle-Income Countries. Working Paper #24. London: Leonard Cheshire Disability and Inclusive Development Centre. GTZ. (2006). Policy Paper: http://www.gtz.de/de/dokumente/en-disability-and-development.pdf. Habib, L. A. (1995). ‘Women and Disability Don’t Mix!’: Double Discrimination and Disabled Women’s Rights. Gender and Development, 3(2), 49-53. Hacker, D (2010). The Gendered Dimensions of Inheritance: Empirical Food for Legal Thought. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 7(2), 322-354. Hopkins, E. W., ed. (1995). The Ordinances of Manu Translated from the Sanskrit. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. (Original printed in 1884). Irianto, S. (2004). Competition and Interaction Between State Law and Customary Law in the Court Room: A Study of Inheritance Cases in Indonesia. Journal of Legal Pluralism, 43 49, 91-113. JICA Sector Strategy Development Department. (2006). http://www.jica.go.jp/english/operations/thematic_issues/social/overview.html. Jolly, J., trans. (1880). The Institutes of Vishnu. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Jolly, J., trans. (1889). The Minor Law Books, Part 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Kameri-Mbote, P. (1995). The Law of Succession in Kenya: Gender Perspectives in Property Management and Control. Nairobi: Women & Law in East Africa, International Environmental Law Research Centre. La Ferrara, E. (2007). Descent Rules and Strategic Transfers: Evidence From Matrilineal Groups in Ghana. Journal of Development Economics, 83, 280-301. Lang, R, Kett, M., Groce, N., Trani, J. (2011). Implementing the United Nations Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities: principles, implications, practice and limitations. ALTER-European Journal of Disability Research. (in press) Loeb, M. E., Eide, A. H. (2004). Living Conditions Among People with Activity Limitations in Malawi: A National Representative Study. SINTEF Health Research. Oslo, Norway. http://www.safod.org/Images/LCMalawi.pdf. Lwanga-Ntale, C. (2003). Chronic Poverty and Disability in Uganda. Paper presented at the conference ‘Staying Poor: Chronic Poverty and Development Policy’, University of Manchester, 7-9 April. Mbatiah, S. (2010). Kenya: Custom Law Trumps New Laws Covering Women’s Land Rights. Inter Press Service, Nov. 23, 2010. Mehrotra, N. (2004). Women, Disability and Social Support in Rural Haryana. Economic and Political Weekly, 39(52), 5640-5644. Meinzen-Dick, R. S., & Pradhan, R. (2002). Legal Pluralism and Dynamic Property Rights. CAPRi Working Paper No. 22. Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy 44 Research Institute. Metzler, I. (2011). Disability in the Middle Ages: Impairment at the Intersection of Historical Inquiry and Disability Studies. History Compass, 9(1), 45-60. Miles, M (2008). Disability and Deafness in the Middle East. Annotated Bibliography. New York: Center for International Rehabilitation Research Information and Exchange. Available at http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/bibliography/mideast/. Miles, M. (1999). Some Historical Responses to Disability in South Asia and Reflections on Service Provision; With Focus on Mental Retardation in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh and Some Consideration of Blindness. Unpublished PhD thesis, UK: University of Birmingham. Miles, M. (2002). Some Historical Texts on Disability in the Classical Muslim World. Journal of Religion, Disability & Health, 6(2-3), 77-88. Mitra, S., Posarac, A., & Vick, B. (2011). Disability and Poverty in Developing Countries: A Snapshot from the World Health Survey (World Bank Social Protection Discussion Paper No. 1109). Monawar Hosain, G. M., Atkinson, D., & Underwood, P. (2002). Impact of Disability on Quality of Life of Rural Disabled People in Bangladesh. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 20(4), 297-305. Müller, M., ed. (1882). Pahlavi Texts, Part II. Sacred Books of the East, Volume 18. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Mwenda, K. K., Mumba, F. N. M., & Mvula-Mwenda, J. (2005). Property-Grabbing Under African Customary Law: Repugnant to Natural Justice, Equity, and Good Conscience, Yet a Troubling Reality. George Washington International Law Review, 37, 949-968. Nauck, B. (2010). Intergenerational Relationships and Female Inheritance Expectations: Comparative Results From Eight Societies in Asia, Europe, and North America. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 41(5-6), 690-705. Palmer, M.G., Thuy, N., Quyen, Q., Duy, D., Huynh, H., & Berry, H. (2012). Disability 45 Measures as an Indicator of Poverty: A Case Study from Viet Nam. Journal of International Development, 24(S53-S68), DOI: 10.1002/jid.1715. Parnes, P., Cameron, D., Christie, N., Cockburn, L., Hashemi, G., & Yoshida, K. (2009). Disability in Low-Income Countries: Issues and Implications. Disability & Rehabilitation, 31(14), 1170-1180. Rahman, A., & Ahmed, P. (1993). Women With Disabilities in Bangladesh. Canadian Woman Studies, 13(4), 47-48. Schlegel, A., & Eloul, R. (1988). Marriage Transactions: Labor, Property, Status. American Anthropologist, 90(2), 291-309. Sivaramayya, B. (1997). Of Daughters, Sons & Widows: Discrimination in Inheritance Law. Manushi, 100, 27-32. Sultana, Z. (2010). Agony of Persons with Disability: A Comparative Study of Bangladesh. Journal of Politics and Law. 3(2), 212-221. Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA). Rehab Lanka Project: http://www.sida.se/English/Partners/Civil-Society-/Results-of-Sidas-civil-society-cooperation/Makinga-difference-/Economic-development/. Talle, A. (1995). A Child is a Child: Disability and Equality Among the Kenya Maasai. In Ingstad, B., & Whyte, S. R., Eds. Disability and Culture. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. Tambiah, S. J., Goheen, M., Gottlieb, A., Guyer, J. I., Olson, E. A., Piot, C., Van Der Veen, K. W., Vuyk, T. (1989). Bridewealth and Dowry Revisited: The Position of Women in SubSaharan Africa and North India [Comments and Reply]. Current Anthropology, 30(4), 413435. Thomas, P. (2005). Disability, Poverty and the Millennium Development Goals: Relevance, Challenges and Opportunities for DFID. London: Department of International Development. 46 Trani J. F., Bakhshi P., Noor A. A., Lopez, D., & Mashkoor, A.(2010). Poverty, vulnerability, and provision of healthcare in Afghanistan. Social Science and Medicine, 70(11), 1745-55. Trani, J.F., Loeb, M. (2012). Poverty and Disability: A Vicious Circle? Evidence from Afghanistan and Zambia. Journal of International Development. 24(S19-S52), DOI: 10.1002/jid. 1709. United Nations. (1979). Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. G.A. Res. 34/180, U.N. GAOR, 34th Sess., Supp. No. 46, at 193, U.N. Doc. A/34/46 (1981) http://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IV8&chapter=4&lang=en.United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. G.A. Res. 61/106, U.N. GAOR, 61st Sess., U.N. Doc. A/RES/61/106 (2006) http://www.un.org/disabilities/convention/conventionfull.shtml. United Nations. (2011) Disability and the Millennium Development Goals: A Review of the MDG Process and Strategies for Inclusion of Disability Issues in Millennium Development Goal Efforts. http://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/mdgs_review_2010_technical_paper_advance_text.pdf US Agency for International Development (US AID). http://www.usaid.gov/about_usaid/disability/. World Bank (2007). People with Disabilities in India: From Commitments to Outcomes. Washington, D.C.: World Bank. World Health Organization. (2010). Community-Based Rehabilitation: CBR Guidelines. Geneva: WHO. World Health Organization and World Bank. (2011). World Disability Report. Gevena: WHO. http://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/en/index.html World Health Organization & United Nations Population Fund. (2009). Guidance Note: Promoting Sexual and Reproductive Health for Persons with Disabilities. Whyte, S. R., & Ingstad, B. (1995). Disability and Culture: An Overview. In Ingstad, B., & Whyte, S. R., Eds. Disability and Culture. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of 47 California Press. Yeo, R. (2001). Chronic Poverty and Disability. Background Paper No. 4. Chronic Poverty Research Centre. Zimmer Z. (2008). Poverty, wealth inequality and health among older adults in rural Cambodia. Social Science and Medicine, 66(1), 57-71. 48