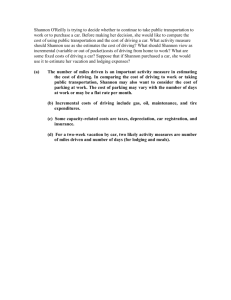

Teachers Management’s grooming me to be assistant manager of the deli,... training the new guy Guillermo. I walk him through...

advertisement

Teachers Management’s grooming me to be assistant manager of the deli, so I’m training the new guy Guillermo. I walk him through all the kinds of turkey, then all the ham, then the other shit like cheese and salami. I ask him about girls and I show him the picture on my phone of my family. Was my wife Shannon’s idea, a mall portrait of us with our son Grayson and his sister Gabby on her 2nd birthday. Shannon framed the good one, but I always show people the shot with our tongues out and Gabby looking terrified. Guillermo shrugs. “These slicers are for meat, that one’s for cheese,” I point. Guillermo keeps itching at the hair net on his head, which is shaved, but rules are rules. We talk about TV shows while I teach him how to operate the slicers, how to dismantle and clean them. The blade whispers through a turkey breast and I hand him a slice to try. “You’ll want a knowledge of all of our product.” He blinks at all of the information. “I‘ll definitely remember some of this,” he says. I tell him nobody gets it all the first time. Working the deli counter is my day job and four nights a week I stock shelves, both jobs at Safeway. I don’t get overtime because its technically two jobs but its money, and when I get my promotion I can quit overnighting. Sometimes I sleep days, sometimes nights, and a few days of every week I just don’t sleep. I wouldn’t do it if I wasn’t a dad, but I wouldn’t be up to anything better without kids. I pound coffee like my dad did beer, but I don’t want to miss a minute of home. My childhood was a lesson in how not to run a house, but learning to do it right has been the rewrite I always begged for. Shannon catches me up on everything while Grayson talks about second grade and swirls dinner with his fork. He loves his little sister, he’s rowdy in the best way, and scrappy as a chicken bone. “Did you learn anything at school today?” Shannon asks. “I learned a joke.” Grayson drinks from his milk while we wait. “Why did the boy throw his clock out the window?” He’s got a milk mustache. “Why?” we ask. Gabby is laughing before the punch line even starts. She’s almost three and she worships her brother. “He wanted to see time fly!” The whole table is in tears. I drop my fork laughing. Everything my children say is a wonder, and in my exhaustion the joke hits me like I’m drunk. The coffee pot stutters and the dishes clink in suds after the kids go to bed. Shannon and I have one quiet hour together before I go in to stock overnight. We spend it on the couch with her head on my shoulder and she listens to my heartbeat, which quickens and throbs as I drain the pot. We kiss at the door and I’m back to Safeway for seven hours. Nobody’s walking their dogs through the neighborhood when I drive home from work, and only a few lights are on in the houses. Stocking works my body, hours of lifting and moving weight. As a father I value strength, and through the hundreds of boxes, I remember the heroism I represent to my kids. I remembered my father at work tonight. Using my own arms, I recalled the strength of his. Stocking is late, slow, solitary, repetitive. I spent hours in the shadow of memories, but in the jostling drive home, just before sunrise, family is the obligation that saves me. I unlock the door and crawl fully dressed into bed. Shannon rolls to face me as I close my eyes at 5:51. It feels like a blink when I open my eyes at 6:15 to the alarm. Shannon goes to Gabby’s room while I nudge Grayson out of bed. He resists dressing and I have to put his socks on for him while Shannon and Gabby, morning souls, sing in the other room. I can still taste old coffee and feel the hair matted to my legs from the pants I haven’t taken off in 24 hours. Shannon’s out the door with a bagel and our children. I’m too tired to take them to school today, but I’m off from the deli so I can sleep for the first time in a while. The mirror shocks me, and I linger on it after brushing my teeth, touching my cheeks and eyes, the tired looking parts. The overnight gig is only a few months in, or maybe a few months is a long time. The bed is so soft I roll in it like a dog in dirt, and I inhale the pillow like a drug. That's when the noise starts. It can’t be anything but construction, but I yank the blinds to confirm. In the light of the morning, hardhatted men in yellow vehicles pound the neighbor’s garage to rubble. The motors, the beeping, the shouting, the blown out radio playing classic rock, the booming crashes and splinters of a building destroyed. The chorus of clatter shakes the walls and rattles my eyes as much as it grinds my eardrums. Chirps and cries fade as all the birds fly to far trees in quieter yards. It looks like a big project, and a three-word question comes to me: weeks or months? I’m cutting boxes open and shelving chips and shampoos, trying so hard not to be upset. It’s 2:00 AM and I got an hour of sleep today because the construction workers went on lunch break at noon. I spent the day sprawled angry in the bed for hours, then took a shower until the hot water ran out, had soup and coffee, and then picked the kids up. Grayson threw a girl’s drawing in the trash so I had to chat with his teacher. He cried with guilt on the ride home and Gabby cried because her brother did. Even my joints are tired. I have a deli shift in eight hours so my boss cuts me early and I almost nod off on the road. It’s only until I’m promoted. That makes this livable. I sleep through the alarm, but the next day of construction starts before I’m even dreaming. “What is that racket?” Shannon says, blinking in the morning. I’m screaming inside. “Construction.” The workers are carting off rubble through the view of the kitchen window. It feels like I’m watching them dismantle my own brain in pieces, then the kids come in. I take a cup of black coffee and a granola bar and I take the kids to school. My hands are shaking but I put on a smile when I drop them off. I drive straight to the Safeway parking lot and nap upright in the driver’s seat until my shift starts. Guillermo knocks on my window and I jump. Work starts in three minutes. I can’t shake the feeling I’m forgetting stuff, so I show him how to do a few things two or three times. The other employees keep glancing at me, then each other. Time passes horribly but it passes. Regulars save me on days like this. I remember their names, what they buy, they ask me about my family and smile. There are the full-time moms and the lunch break suits that change their orders and talk on the phone, make prissy specifications about gluten allergies and never thank you. It would depress them to know I’m a father, to know this is what feeds a family. Sometimes it depresses me too. Five days a week in the deli and four nights stocking in a place where the lighting never changes. On most days, I remember the dad I had and the one my kids have, and that is plenty. I was one year younger than Grayson the first time he hit me. I take care of my family with paychecks, but also with kindness. Humanity defines fatherhood. That’s what I usually say. But I can’t stop yawning. I can’t string two thoughts together. The only movement in the bedroom is the occasional crawl of striped light sweeping across the walls as cars pass. I can tell by her breathing that Shannon’s not really asleep, but she’s facing the other way. I’ll fall asleep in a moment, just as soon as I stop feeling bad enough to be awake. I got home from the deli exhausted, feeling sick in my brain. That I had forgotten about the planned night out with Shannon felt inevitable. I had to get gas on the way. That, with the steakhouse dinner, two movie tickets, and sitter who cleared our fridge, went over $200. I did the math in hours at Safeway. I did not do much talking. The night to reconnect was such a letdown for Shannon when we both needed it not to be. She worried about me, petting my knuckles on the tablecloth. Exhaustion didn’t seem like the answer she wanted. “Are you angry about something?” I took almost a minute to reply. “I’m just running low.” I could barely think. I fell asleep in the movie theater. I ran a red on the way home. Shannon told me I kept slamming doors, but it wasn’t on purpose. Sex wasn’t in the cards, and I could only call that a relief. It’s dark. The construction starts again in about seven hours but I feel awake. “Am I a good dad?” I whisper. I wonder how often my father asked that question, and how my mother answered him. He’s been in my thoughts a lot at work. Shannon doesn’t answer. Maybe she really is asleep. Guillermo cut the tip of his finger off on the slicer today. Blood sprayed across the whirring edge, dotted the floor, got everywhere. It got on me and I yelled in his face. I still have my job, but managers don’t yell. Goodbye promotion. The bags under my eyes are dark and swollen like ripe fruit. My eyeballs feel pickled, wet and dry at the same time. I just want to close them so badly. The sun is low in the sky, but I can’t remember if it’s supposed to be rising or setting. I feel like a stray animal. It’s been two weeks since construction started smashing my off days. The men next door hammer and drill like ceaseless demons. Whatever they’re building isn’t even close to done. It smells like dust and engines when you open the windows and it looks like a crash site. It sounds like the crash is still happening. Shannon, Grayson, and Gabby are like ghosts to me. I never have a single thing to say. I sleep on my nights off but it isn’t enough, and it’s only getting worse. Guillermo’s blood is on my shirt. I stop at a green light, and I accidently blow the horn when I notice. My body feels sewed together. The kids should be home from school. When the tires chew gravel up our driveway, Shannon is waiting for me with her arms crossed, wind flinging her hair around. She meets me at the car door. “Handle Grayson.” She points to the open front door. Gabby’s watching TV when I come in, some loud cartoon. Grayson is running through the house in his underwear and there are frosted flakes scattered all over the carpet. He shrieks with laughter when he sees me. He is a volcano in 2nd grade, running towards me, and I am so worn down and going back to work in five hours. Handle Grayson. From behind me I hear a scream, “what are you doing!” It’s a scream I hear twice at once. The first is in Gary, Indiana 23 years ago from the mouth of my mother. I watched her say it through my left eye, the right already swollen closed as my dad slams me down on the coffee table so hard the wood cracks. I’m six years old and I’ve never broken a bone before, but my arm is the wrong color and I can’t move my fingers. I’m just as sure that I’ll never forget the speed and power of a grown man’s fists, as I am that I’ll never remember why they were pummeling me. The other scream is happening right now, in Shannon’s voice. She’s pulling at my shirt so hard it’s tearing but I can’t think anymore, I can’t feel her resisting. I feel Grayson’s arm in my hand. I feel a weight, maybe 50 pounds, whooshing through the air and into the wall. The world moves in a syrupy curtain of white. They call it seeing red, but my vision is full of white. The voices in the room sound so far away, just dim high-pitched embers. There’s still a tiny arm in my grip. I don’t know what happens next. I don’t even know what’s happening in this moment.