RP-2002-0130 YEAR 2003 RATES UNION GAS LIMITED DECISION WITH REASONS

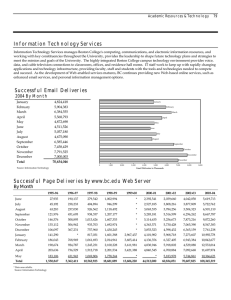

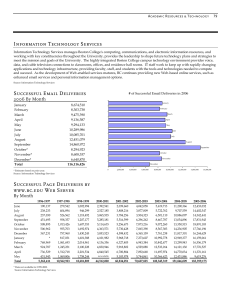

advertisement