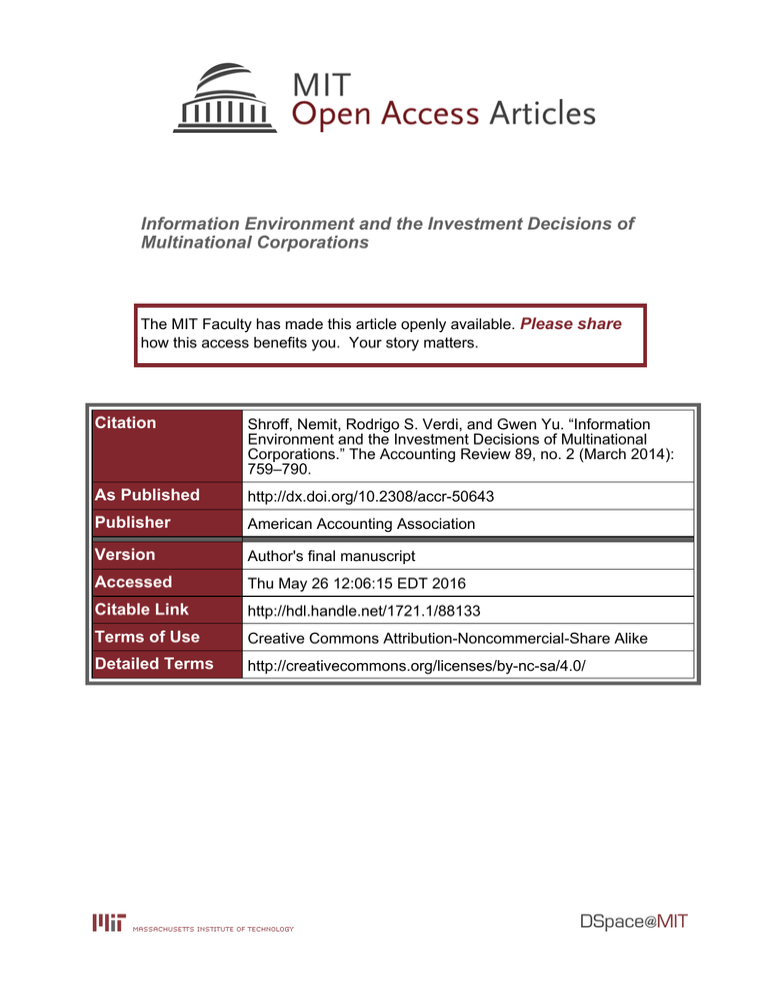

Information Environment and the Investment Decisions of Multinational Corporations Please share

advertisement