So You Think You Can Dance? Lessons from the US

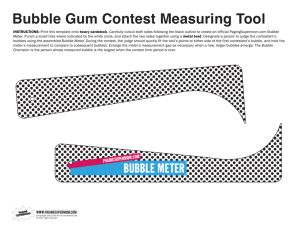

advertisement