Document 12207226

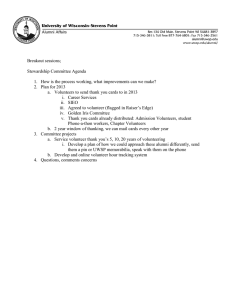

advertisement