EXAMINATION OF SELECTED OCCUPATIONS

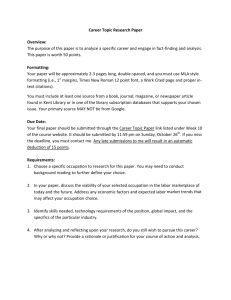

advertisement