STRATEGIC SOURCING IN THE AIR FORCE

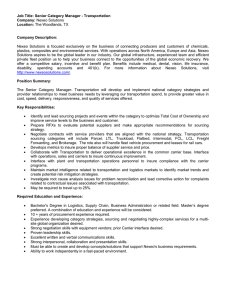

advertisement