S E M PECIAL

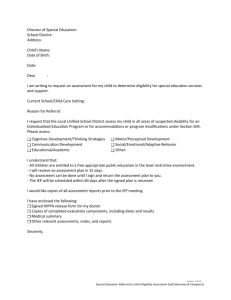

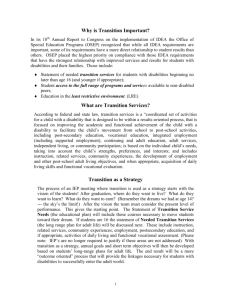

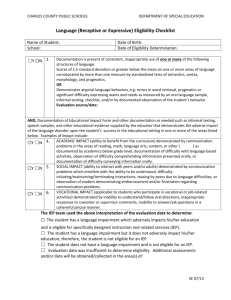

advertisement