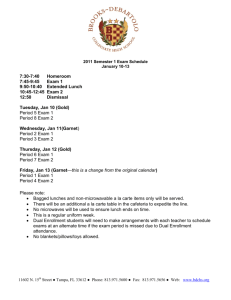

This article was downloaded by:[University of Puget Sound]

advertisement

![This article was downloaded by:[University of Puget Sound]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/012187422_1-66bc95176e50d28542b02417cc2568e3-768x994.png)