6 om as a public service of the RAND Corporation.

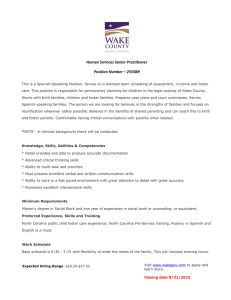

advertisement