W O R K I N G Invisible Wounds

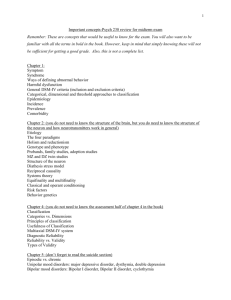

advertisement