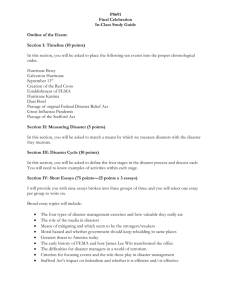

W O R K I N G Models of Relief

advertisement