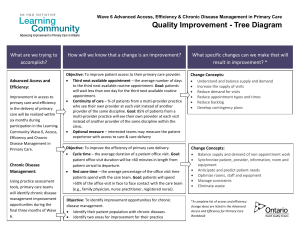

Improving Care for Chronic Conditions Programs Research Report

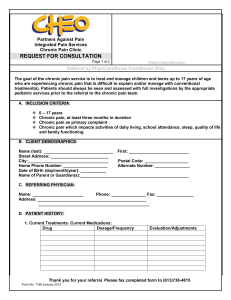

advertisement