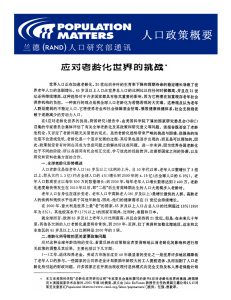

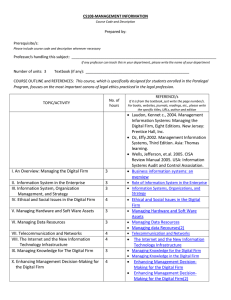

DECISIONMAKING IMPROVING IN A TURBULENT WORLD

advertisement