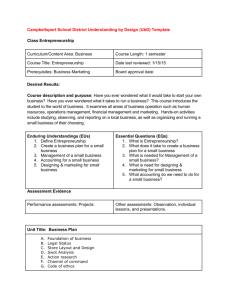

GLOBAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP MONITOR REPORT

advertisement