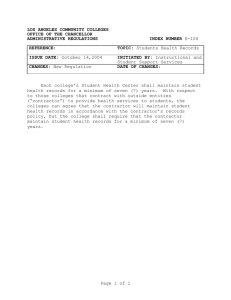

R Implementing Performance- Based Services Acquisition (PBSA)

advertisement