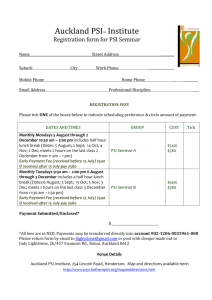

W P

advertisement