The international dimension of research and innovation cooperation

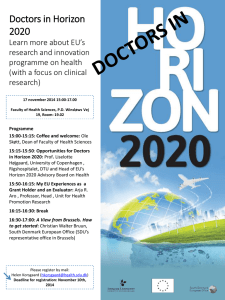

advertisement