Plant Succession Due to Overgrazing in the Agropyron Bunchgrass Prairie... Washington Author(s): Rexford F. Daubenmire

advertisement

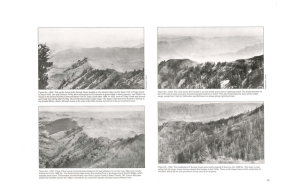

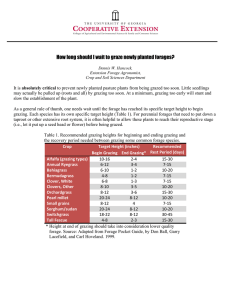

Plant Succession Due to Overgrazing in the Agropyron Bunchgrass Prairie of Southeastern Washington Author(s): Rexford F. Daubenmire Reviewed work(s): Source: Ecology, Vol. 21, No. 1 (Jan., 1940), pp. 55-64 Published by: Ecological Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1930618 . Accessed: 13/07/2012 12:13 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. . Ecological Society of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Ecology. http://www.jstor.org PLANT SUCCESSION DUE TO OVERGRAZING IN THE AGROPYRON BUNCHGRASS PRAIRIE OF SOUTHEASTERN WASHINGTON REXFORD F. DAUBENMIRE University of Idaho matic climax in essentiallyvirgincondiseveral stages of retrogression, tion, and During the period when southeastern in end some cases the point in this biotic Washingtonwas settledby whiteman the bunchgrassprairies,which covered large successionappears to have been attained. areas in thisregion,were used chieflyfor CLIMATE grazingcattle. This industryhad scarcely become establishedwhen it was demonPrecipitationrecordswithinthearea of stratedthat the deep loessal soils charac- studyconsistof observationsfrom 1899 teristicof the region were excellentfor to 1903 at Hooper, Washington (U. S. growingwheat. Startingabout 1880 this D. A. Wea. Bur., '36). During this new typeof land use began to replacethe periodthe mean annual precipitation was earlier,and by about 1910 all areas ex- 31.2 cm.,whichincludesa snowfallaverceptthoseon whichcultivationwas either aging 26.7 cm. each year. Calculations impractical or impossible had been based on considerablylonger records at broughtinto cropland. The remaining Lacrosse and Lind, whichare just outside areas, the so-called "scablands," where the area studied,indicatethatthe average the soil is shallow,or stony,or the sur- precipitationat Hooper is approximately face is too frequently interrupted by such 29 cm. outcrops,have remainedas grazinglands Considerablyover half the annual preand probablywill be used in this manner cipitationoccurs duringthe winter. Alin the future. Within the last few mostexactlyhalf of the annual sum falls decades the livestockindustryin this re- during the four months of November, gion has undergonea secondgreatchange December,January,and February. due to the replacementof the cattle by At Lacrosse theaveragemaximumtemperatureof the hottestmonth (July) is sheep over mostof the rangelands. Whereverthe soil of the non-agricul- 31.50 C. withtheaverageminimumof the tural land was deeperthan about 1.5 dm. coldestmonth(February) - 60 C. The and was not sandy, the original bunch- average annual extremesof temperature grass cover was apparentlyidenticalwith are 430 C. and - 330 C. Some evaporationfiguresfor the sumthat of the deeper soils. As a resultof long continuedheavy grazing of these mer monthsare available (U. S. D. A. grasslands,the appearanceand the forage Wea. Bur., '36) for Lind, Washington, value of the primevalprairie have been which is situated about 43 kilometers considerablychanged. The bunchgrass,a northwestof the center of the area of climaticclimax, has undergonea retro- study. These data make possiblethe calgressionwhichin many cases has culmi- culation of the precipitation/evaporation nated in a biotic climax. The latter is ratiosforthe summermonthsat thatstaas permanentas the presentsystem of tion (table I), and such ratios are probspring-fallsheep grazing. ably very similarto those in the region An excellentopportunityof studying wherethe successionalstudieswere made. The growingseason ends in earlysumthis vegetationalretrogressionexists today in northeastern FranklinCountyand mer at which time the soil moisturebeadjacentWhitmanCounty. Here, in dif- comes practicallyexhausted. During the and early fall the sheep ferentareas, exist fragmentsof the cli- drymid-summer INTRODUCTION 55 56 REXFORD Ecology,Vol. 21,No. 1 F. DAUBENMIRE insure a relativelyuniformclimateat all stations. In every case the topographyis quite level. Evapora- PrecipitaMonth tion tion Prec./Evap. ratio To demonstrate thatthesoils at each of in cm. in cm. the four studyareas are well withinthe April 13.60 0.81 .059 range of texture (which is one of the May 19.14 1.27 .066 mostimportant aspectsof soils in thisreJune 21.74 2.03 .093 July 27.75 1.02 .037 gion) and depthwhichallow a good deAugust 22.97 1.17 .051 velopmentof the bunchgrassassociation, September 13.85 2.46 .178 a comparableseries of wiltingcoefficient determinations was made at each station. are taken to the mountainsfor grazing. The water-holdingpower of the soil as In late fall whenthe rainyseason returns, indicated by the wilting coefficients in the perennialgrasses and forbsand a few table II, is in all cases well withinthe annualssuch as Bronsustectorumput out new leaves and again affordgreen forage TABLE II. Wiltingcoefficients of soils as deindirectly fromthehygroscopic coefficients untilthe colderpart of winter. In mid- termined winter,whenno otherforageis available, (W.C. = H.C.10.68) thedead shootsof Agropyronare grazed, Decimeter Station Station Station Station at which time theymay be eaten to the horizons 1 2 3 4 groundline. TABLE I. Some average precipitation and evaporation data at Lind, Washington: 1926 through1930 (U.S.D.A. Wea. Bur., '36) METHODS 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7.9% 9.5 8.1 8.0 7.0 6.6 8.4 8.9 10.3 9.2 9.7 7.9 8.9 9.2 9.0 8.3 8.9 8.2 9.0 8.5 7.6 8.5 8.7 Most studies of plant succession,including the present one, are made by analysinga group of associationswhich are thenarrangedin a sequenceillustratingtheinvestigator's conceptof thestages range which is favorable to this comthroughwhich the final stage has gone. munityin our region. Otherobservations Such a procedureis necessarychieflybe- by the writerhave shownthat this assocause of the greatexpanse of timewhich ciation is apparentlynormallydeveloped would be requiredto observethe succes- in this region on soils as shallow as 1.5 sion frombeginningto end on the same dm., a soil depthwhichis well exceeded plot. This methodopens a way for fal- on all the areas studied. lacious conclusions,since one of the most A checkon theuniformity of the origifundamentalprinciplesof the scientific nal cover is the presenceof all of the methodcan be so easily violated. Obvi- dominantor characteristicplants in the ously,a studyof the effectsof variation immediatevicinityof all stations. Careof a singlefactorbecomesignificant only ful attentionto this point indicatedthat when all other factorsremain constant. the originalvegetationwas at least florisIn any studyof the grazing factor,one ticallycomparablein all cases. musthave evidencethattheoriginalvegeThe area of bunchgrasswhichapproxitationwas essentiallyidenticalat all the matesthe virginungrazedconditionis on stationswhichare analysed,and that the a spur projectinginto the Palouse River environment, except for the herbivores, Canyon. When the railroad was built was uniform. parallel to the canyon,the end of this All stations occurred within an area spur was severedfromthe remainderof having a diameterof 32 kilometersand the prairieby a steep-walledcut about 10 the elevation varied from 292 to 445 m. deep,and thushas remainedabsolutely metersabove sea level. These features freefromgrazingfortwenty-seven years. January,1940 AGROPYRON BUNCHGRASS conOtherareas apparentlyin near-virgin dition are very similar to this stand, hence the assumptionof its undisturbed natureseemsto be well supported. The abundance and stature of the Agropyronplants was taken to be an indicatorof the relativeseverityof grazing. Actual records of the kinds and numbersof animals and the periods of if not imposrangeuse would be difficult sible to ascertainand to evaluate in the PRAIRIE 57 areas studied. The decrease of palatable plantsand increaseof non-palatableones bothpointto the validityof my assumptions of the proper sequential arrangementof the stations. A statisticalcomparisonof thesegrazed and ungrazed areas of grassland was made by the frequencymethod. In each of fourareas considered(figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4), a stationconsistingof 100 frequency plots was studied. The plots were 2 X 5 FIG. 1. Station 1. An area whichwas lightlygrazed priorto 1911,and typicalof the associationin virgincondition.The domiwhichis apparently 85 per cent of the annual forageoutput nantAgropyronbunchescontribute withthesmallerinterstitial plantsof Bromusand Poa each in thiscommunity, 5 per cent. The stake is markedoffinto decimeterunits. All contributing fourpicturesweretakenon May 21, 1938. the smallestAgropyron FIG. 2. Station2. Heavy grazinghas eliminated bunchesand reducedthe size of thoseremaining.The groundis developinga coverof smallplants,partof whichare annualsand partperennials. 58 REXFORD Ecology,Vol. 21,No. 1 F. DAUBENMIRE FIG 3 Station3 Agropyron bunchesare eaten back to the groundline so thatthe shortweak shootswhichare put fortheach year can be distinguishedonlywithclose study. . . . .... :.;..... ............. :....... ..... . ..| .. . ; ......... ................................................ ........ ....::: .~~~~~W ...; ..... ..... ..~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ eliminated is completely FIG. 4. Station4. Agropyron here,but the soil is of small unpalatableplantswhichis fairlywell coveredwith a community dominatedby the perennialPoa secundaand a groupof annual dicots-apparentlya bioticclimax. groups. Group one includes those species which decrease in abundanceas the intensityof grazing increases. This decrease in some if not most cases seems directlydue to stock eating the aerial shoots. In perennials,suchas Agropyron, organsbecomeweakened theunderground caused by the due to undernourishment tissue, repeatedremovalof photosynthetic RESULTS and the declinein vigorof such plantsis In table III the species encounteredin gradual until the plant succumbs. With all 400 plots are classified into four an annual which is grazed, such as dm. in dimensions,and were arrangedin fiveparallelrows one meterapart. Each plot of the400 was studiedat threecritical dates (April 7 or 8, April 30 or May 1, and May 21 or 22) which were so timedon a basis of previousobservations that the entire vascular flora (part of whichis veryephemeral)couldbe studied. January, 1940 AGROPYRON BUNCHGRASS Brotus tectoruns, thefirstfewyearsduring whichthe stockfeed on the plantsso heavilythatno seeds are maturedspell a rathersudden extinctionof these plants from the range. Scatteredgroups and individuals of Broinus seem to escape grazingand smutepidemiceach year and TABLE III. Behavior under influenceof heavy grazing 59 PRAIRIE thesematurea few seeds whichare scattered somewhatby the sheep, perpetuating the species in a verythinpopulation. In this same group theremay be other causes forthedisappearanceof theplants. Some of those species which are not grazed, such as Lithospermumi, may owe Frequency of plants as affectedby grazing. Presence in the community,althoughnot frequentenoughto have beenincludedin one of theplots,is indicatedby + Annual (aa) or Bi- perenCli- Early Late otic nial rematic reclimax trogr. trogr.climax (P) Per cent frequency of occurrence Species * Agropyronspicatum (Pursh) Scribn. & Smith Bromus tectorum L... & GayophytumramosissimumT. 6.t................. Agoseris heterophylla(Nutt.) Greene............. Achillea lanulosa Nutt............. CalochortusmacrocarpusDougl .................. Decreasing Lomatium macrocarpum(Nutt.) C. & R .......... in Astragalus spaldingii Gray..................... Frequency Erodium cicutarium(L.) L'Her .................. Gilia gracilis Hook ............................. Lagophylla ramosissimaNut.................... Festuca idahoensis Elmer....................... Lomatium triternatum (Pursh) C. & R ............ ....... SisymbriumlongipedicellatumFourn....... LithospermumruderaleDougl ................... 70 100 58 16 6 4 3 2 1 1 1 + + 1 + Plantago purshii Nutt.......................... Plagiobothrystenellus(Nutt.) Gray.............. .53 . Cryptantheflaccida(Dougl.) Greene Pectocaryapenicillata (H. & A.) A. DC var. elongatum(Rydb;) Thell. Increasing in Lepidium densiflorum Frequency Lappula redowskii(Hornem.) Greene............ Erigeronconcinnus (H. & A.) T. & G Antennaria dimorpha(Nutt.) T. & G. Agoseris glauca (Pursh) Steud................... Stephanomeriapaniculata Nutt 84 12 Apparently Characteristic of Intermediate Stages 53 3 17 9 3 22 31 4 9 + 6 + + + + 100 28 56 3 2 2 25 LithophragmabulbiferaRydb.................... 63 Festuca pacifica Piper.......................... .79 . Alchemilla occidentalisNutt L... . Sisymbrium'altissimum .27 Lomatiumfarinosum (Hook.) C. & R. Madia exigua (Sm.) Gray...................... + . . Delphinium nelsoni Greene . ....... Ranunculus glaberrimusHook 98 100 100 70 69 61 2 99 100 21 100 100 Poa secunddcPresl............................. Frequency Draba vernaL .................................. Scarcely Brodiaea douglasii Wats........................ Affected mosses (all Bryales).99 1 1 + 100 100 100 79 67 32 30 8 6 2 aa aa aa aa aa aa p p p aa 36 8 p aa aa aa p aa p p 2 10 + 1 100 2 + + p aa aa p p p p p aa aa aa p p aa P + 2 32 2 1 100 + 2 2 100 100 66 100 100 100 23 100 p aa p p * Includes A. inerme (Scribn. & Smith) Ryd. which is considered by the writeras one formof A. spicatum (Daubenmire, '39). All have identical ecology in our region. t This species and Epilobium paniculatumNutt. cannot be distinguishedby vegetative structures, and since veryfewofthe plants flower,both species have been lumped underthe name ofthe one which seems to be the most abundant. 60 REXFORD F. DAUBENMIRE theirextinctionto trampling. Still others may have a more remotecause for decadence, namely,the removalof protection affordedby the largerand morepalatable plants. That this can be a potent factoris well shown by the great reductionin statureof Poa in the bioticclimax (or even in the spaces betweenthe Agropyronbunchesin the climaticclimax) as compared to specimens close up under Agropyronbunches. Those in the latter situationare from 50 to 100 per cent taller, apparentlydue to the protection from insolation and desiccating winds which the tall plants afford. fromthe standpointof It is significant range managementthat 90 per cent by dryweight,of the total annual outputof shoots in the Agropyronbunchgrassassociationis producedby two membersof this group of species (Agropyron85 per cent and Bromus 5 per cent). The amount of this forage available in the bioticclimax is negligible. A second group containsthose species which seem to be favored by grazing. These plants for the most part are not palatable (except for the basal leaves of LepidiumandAgoserisand smallamounts of the young shoots of Cryptanthe),are not seriouslyinjured by trampling,and theirshootscan withstandexposureto the full force of dryingwinds and intense insolation. Apparentlythese species are kept out of the climaticclimax by the affordedby the dominantsof competition that community.This competitiveinfluence of other plants seems more detrimentalto thesespecies than the influence of the animals. Most of the plants in this group are small annuals, and members of the Boraginaceae are conspicuous among them. Some may be avoided because they are woolly (Plantago), others because theyare hispid (Lappula) or otherwise distastefulto stock. Certainof them may escape only because theirfoliageappears at the same timeas thatof a more desirablespecies. In the case of Festuca pacifica the foliage is extremelyscanty Ecology,Vol. 21,No. 1 and the stems wiry. Obviously these plantsmake up mostof the bioticclimax. A thirdgroup of speciesis made up of plants which appear to be immediately benefitedby the removalof the competitiveinfluenceof theclimaticclimaxdominants, but which are not very well adapted to the biotic and aerial factors whichaccompanythefinalstagesof range deterioration.The conditionswhich favored group two also favor this group during the early stages of overgrazing, but some or all of the factorswhichoperate againstgroup one finallycome into play so that these plants are ultimately eliminated. Most of thesespeciesare primarilyseral,beingpracticallywithoutrepresentationin eitherclimax. The fourthand last categoryis an assemblage of hardy unpalatable plants whoseabundanceseemsscarcelyincreased or reduced by the radical changes in bioticand aerial factorswhichare brought about by intensegrazing. All were present in the climaticclimax,have persisted throughoutthe period of deterioration, and are importantmembersof the biotic climax. One plant in this last group, Poa secunda, deserves special mention. This bluegrassformsabout 5 per cent of the total shoots (by dry weight) produced annuallyby the vegetationunderclimatic climax conditions. The forage value of thisspeciesovermostof its rangeis rated as fair, and the average heightis about 3 dm. (U. S. D. A. For. Ser., '37). As the protectiveinfluence of the larger plantsin our regionis removed,the stature of Poa decreases until the plant is considerablybelow this average, and the leaves becomeso fineand wirythatthey are scarcelyever eaten by any class of livestock. Undoubtedly the nature of thisplant'sresponseto the removalof the larger and more palatable Agropyronis the key factorin its persistenceinto the bioticclimax. The climateof thisregion, withits extremelydrysummers,probably emphasizesthis phenomenon. From the foregoingit is evidentthat January,1940 AGROPYRON BUNCHGRASS plant successionleads from the climatic climax of Agropyron-Poa-Bromus to a bioticclimaxdominatedby Poa and small annual dicots among which membersof the Boraginaceaeare conspicuous. This process is not marked into recognizable stages. Animal influenceresultsin bare areas only where tramplingis excessive, such as around a corral or bedding ground. Since Agropyronand Bromus together form90 per cent of the climaticclimax vegetationand nearly100 per centof the valuable forage,any plan of range managementwhich maintainsthe vegetation in a conditionmost nearlyapproximating the virginstate would be most desirable. Althoughno extensivestudyhas yetbeen attempted to determine themostappropriate grazingsystemin thisregion,someobservationsby the writerare significant in this connection. Several clippingexperiments weremade in easternFranklinCounty. When Agropyron was clipped to the ground at the heightof its growingseasonin latespring, mostof theclippedplantssuccumbed,and the nextyear the few survivorsproduced only small tufts of foliage with no inflorescences.On the otherhand,grazing the Agropyronbunches to the ground PRAIRIE 61 during the summerand fall appears to have only slight detrimentalinfluence upon theplants. The writerhas observed a fence-corner relic of this associationin WhitmanCounty,whichhas remainedin fair conditiondespite the fact that livestockwhichare turnedintothe fieldafter the wheat is harvested often graze the Agropyronto the ground during this periodof vegetationalaestivation(figs. 5 and 6). These observationsindicatethat a desirablegrazingsystemwould emphasize fall or winter utilizationof cured shoots and minimizespring use of the range. In anotherexperiment,single bunches of Agropyronwere released from the competition afforded by surrounding plantsby keepingthe latterclippedto the ground. The experimental plantsshowed no great responsethe subsequentseason, but by the thirdyear the increasein size and vigor was very apparent,so that it may be concludedthatcompetition checks the stature of even the most dominant plantsin the association. Withintheareas whereAgropyronwas practicallyeliminatedby clipping,some of the annuals, chieflyBromus, Erodium, Lagophylla, Plagiobothrys and Sisymbriumlongipedicellatum showed increase April 7. Agropyronin the pastureto FIG. 5. WhitmanCounty,Washington, the left of the fencewas grazed to the groundduringthe precedingautumn. Near-virginprairieto the rightof fence. The soil here is abouta meterdeep; to theexcavationof a deep thestoneson thesurfacewerethrownthereincidental road cut to the rightof the photograph. 62 REXFORD F. DAUBENMIRE Ecology,Vol. 21,No.1 FIG. 6. Photographof the same area shownin figure5S taken on May 21 afterthe Agropyronwithinthe pasturehad attainednearlythe size of the ungrazedplantsto therightof the fence. The bunchesoutsidethefenceare denser and lighterin color due to the presenceof old bleachedshoots. Sisymbrium is conspicuouswithinthe pasture altissimum in size the firstyear,and increasein numbers on subsequentyears. Lappula has a strongtendencyto invade these clipped areas. These clippingexperimentsshow that there is considerablecompetitionamong thedominantplants(Agropyronbunches) as well as betweenthemand the subordinate annuals. When Agropyronis weakened or destroyedby injury during its period of active growth,the lesseningof competition allows the annual florato expand so that the ground surfaceremains well covered. Althoughvaluelessas forage, theseplantsof the bioticclimaxhave distinctvalue as soil bindersin as much as they are fairly efficientin retarding erosionof the topsoil. DIsCUSSION The above studies,togetherwith other observationsby the writer,bringout the factthatthe ecologicresponsesof several plants in Washingtonare different from theirresponsesto grazingin otherparts of the western United States, as indicated by the literature. Four plants deserve special mentionin this connection: Salsola kali L., Bromus tectorum,Agropyronspicatum,and Artemisiatridentata Nutt. In the recentsummaryof range conditionsin the westernUnited States (U. S. D. A. For. Serv., '36), some generalreferencesare made to the behaviorof these plants in regions where Agropyronspicaturn is dominant. These references seem to be based on researchesin the regions to the south and east of Washington since no previous study of grazing successionin this state has appeared. It will be evidentfromthe followingdiscussion that in Washington,which includes only a small part of the total Agropyron rangeland, conditions apparently exist whichare not typicalfor the range as a whole. Salsola, this source states, is widely distributedin some parts of the bunchgrass range. In our particularregionit is closelyconfinedto road right-of-ways, and seems whollyincapable of invading virginor grazed pasturesin this prairie type. Bromus tectorumw, this accountalso remarks, "is now dominatinglarge areas formerlyoccupiedby bunchgrass." This is true in Washington,but the statement needs qualificationhere. Bromus does not dominate ranges which are being heavilygrazed duringthe springseason. When, after heavy grazing, herbivore January, 1940 AGROPYRON BUNCHGRASS pressure is reduced, Bromus quickly dominatesthe area, the other species of the climax enteringmuch later. Patches where the densityof this plant is very high occur throughout all grazed areas in this region. These may possiblybe explainedby a lack of uniformity in spring grazing,coupled with the readinesswith whichthe species will entergrazed lands. If on two or more successive years, a given area escaped grazing during the short vernal season when Bromus is highly palatable, this grass would undoubtedly dominate the area. These island-likepatchesof Bromnus increasein abundance with distance from watering places, a fact which is in harmonywith this explanationof theirexistence. That the Bromus colonies are not the simple and directresultof overgrazingis indicated by the extensivegaps betweenthe colonies,whichgaps are heavilyused by the sheep. Smut infectionsare not responsiblefor the interstitital areas because the Brornus islands show strong conformitywith fences whereverthese result in unequal grazingintensityin adjacent pastures. There also seem to be other factors (perhaps cultivation,fire, etc.) which promotedense standsof thisgrass,but it is not to be consideredhere as a species directlyfavoredby overgrazing,for it is highlypalatable and is practicallyeliminatedby uniformly heavyspringgrazing. Again, it is statedthatin some regions the Artemnisia tridentateassociationmay enterand dominatean area whichbefore grazing contained little if any of this shrub. This cannotbe said forWashington, however,for the writerhas seen no evidenceof this phenomenonalthoughhe has lookedforit forthreeseasons. Communitiesof Artemisiatridentataare commonin the regionwherethepresentstudy was made,but theseare to be foundonly on sandy soils of stream terraces and never show the slightesttendencyto invade the surroundingfiner-textured uplands from which most or all of the bunchgrasshas been grazed. PRAIRIE 63 Agropyronand Artemisiaseem to be ratherthan competitive complementary in centralWashington,whereasin southern Idaho the competitionbetweenthe same speciesis keen. In partsof the latterregion overgrazingtendsto resultin a pure stand of the shrub,while completeprotectionfromgrazing allows the grass to becomeat leastequallyas important as the shrub in the climaticclimax (Craddock and Forsling,'38). Any peculiaritieswhich may exist in the behavior of plants in southwestern to Washingtonmaypossiblybe attributed severalpeculiaritiesof the climatein this region. In contrastto regions farther south and east, the climatein this north arm of the Columbia Plateau is characterizedby considerablygreatercloudiness (Kincer, '22, p. 44) and less insolation (Kincer, '28, p. 33), with a consequence that the average relativehumidityat 2 P.M. is higherat all seasons (Kincer, '22, p. 45). Althoughthe total precipitationis not significantlydifferentbetween the two portionsof the Plateau (Kincer, '22, p. 30), thehighermoisturecontentof theair resultsin a higherprecipitation/evaporation ratio for the frostless season in Washingtonthanin southernIdaho (Livingstonand Shreve, '21, p. 342). Winter temperaturesseem also to be influenced by the humid air which blanketsthis northernregion. Judging fromthe numberof days with the minimumtemperature below freezing(Kincer, '28, p. 9), the wintertemperaturesare less severein Washingtonthanin Oregon and southernIdaho. These climaticdata indicatethat sufficient differences in climatemay exist to accountfordifferent ecologicresponsesof Agropyron,Artemisia, and other associated plants,in Washingtonand in regions farthersouth. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writerwishes to express his indebtedness to the Northwest Scientific 64 REXFORD F. DAUBENMIRE Association for supportingthese studies witha ResearchGrant,and to Mrs. Daubenmire for valuable assistance in the field. Ecology,Vol. 21,No. 1 midity. Atlas Amer.Agr. Part II, Sec. A: 1-48. U. S. Govt. Print.Office. 1928. Temperature, sunshine, and wind. Atlas Amer.Agr. Part II, Sec. B: 1-34. U. S. Govt.Print.Office. Livingston,B. E., and F. Shreve. 1921. The LITERATURE CITED distributionof vegetation in the United States as related to climatic conditions. Craddock,G. W., and C. L. Forsling. 1938. Carn. Inst. Wash. Publ. 284: 1-590. The influenceof climate and grazing on spring-fallsheep range in southernIdaho. U. S. D. A. Forest Service. 1936. The western range. Senate Document199: 1-620. U. S. D. A. Tech. Bull. 600: 1-42. . 1937. Range plant handbook. U. S. Daubenmire, R. F. 1939. The taxonomy Govt.Print.Office. and ecology of Agropyron spicatum and A. inerme. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 66: 327U. S. D. A. Weather Bureau. 1936. Cli329. maticsummaryoftheUnitedStates. Sec. Kincer, J. B. 1922. Precipitationand hu2: 1-40.