Exploring the Evidence: Reporting Research on First-Year Seminars Volume IV

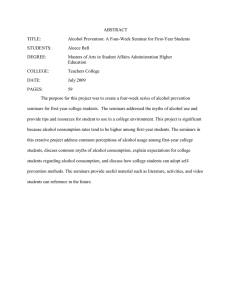

advertisement