Chapter 1 The Importance of Rivers

advertisement

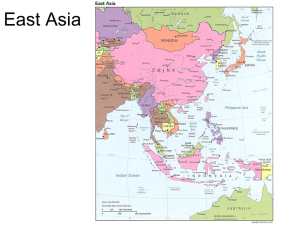

Chapter 1 The Importance of Rivers 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. Why Study Rivers? Rivers as Landscape Elements in the Arts Rivers as Hazards Rivers as Resources Rivers as Recreational Assets Rivers as Transportation Corridors Rivers as Habitat Rivers as Legal Boundaries Rivers as Geomorphic Elements and Agents The River System Some Further Reading What’s next? 1. Why Study Rivers? Because they’re there! This may seem like a flippantly glib answer to the question but it is truly why rivers are important to geographers and to geomorphologists. Rivers and their drainage basins constitute a basic building block of our planet’s physical landscape and societies everywhere are deeply influenced by their presence. Rivers are both a virtue and a curse to society and understanding how and why they function as they do is a very important challenge to both the physical and social sciences as well as to planning and river engineering. This chapter is a preamble that will touch briefly on some of the roles played by rivers before we begin to delve into the physical science of fluvial geomorphology. It is designed to offer you some examples of the importance of rivers and is not meant to be exhaustively comprehensive; you are encouraged to think about these things and to add your own examples as we go along. 2. Rivers as Landscape Elements in the Arts Rivers are a pervasive element in the landscape and for many people represent the defining quality of particular places. Writers and visual artists have been captivated by rivers forever it seems and have for as long as humans have been recording their feelings about their environment sought ways to express the aesthetic and romantic images that rivers seem to conjur up. Perhaps this fascination with rivers reflects the notion that the water they carry is essential to life itself. Perhaps part of the fascination also derives from the movement of water (like the captivating movement of fire) that seems to invest rivers with the quality of life. For whatever reasons, Hickin: River Geomorphology: Chapter 1 writers and artists are drawn to rivers and our literature and painting are heavy with their presence. Perhaps one of the most famous purveyors of stories about river life (in English) is Samuel Langhorne Clemens (Mark Twain) whose 19th century novels (particularly Adventures of Huckleberry Finn) and short stories about the Mississippi River and the river communities along its wandering course are such an important part of American literature. The Mississippi River is of course, one of the most written-about rivers in the world. Closer to home, and more recently, we see rivers as the centrepiece of Canadian novels such as Cheryl Tardif’s The River (set on the Nahanni River in the Northwest Territories) and images of rivers are used as a literary device in works such as Margaret Laurence’s The Diviners among many others. Rivers have a similar place in French language works. For example, the St. Lawrence River is at the heart of many Quebec novels (Anne Hébert's Kamouraska, Réjean Ducharme's L'avalée des avalés), poems (in works of Pierre Morency, Bernard Pozier), and songs (Leonard Cohen's Suzanne, Michel Rivard's L'oubli). A recent Australian historical novel set in the Hawkesbury River Valley is Kate Grenville’s The Secret River. Non-fiction books on rivers are also abundant with Hugh Maclennan’s Seven Rivers of Canada being a notable Canadian contribution along with American John McPhee’s The Control of Nature. Even Environment Canada makes the water/culture connection on its WEB page concerned with Canadian water resources! (http://www.ec.gc.ca/water/en/culture/ident/e_words.htm). But it is in landscape painting that rivers perhaps claim their most significant cultural presence. They almost constitute a genre of their own in art history and a visit to any art gallery will almost certainly produce an encounter with a riverscape. In Britain landscape painting of the 18th century evolved from an elitist form (catering to wealthy landowners) into a rather poetic vision and painters provided a romantic ideal of landscape as a source of timeless values which could be enjoyed by everyone. Famous landscape artists like Gainsborough and Constable present the landscape as a place of rest and solace and this comforting mood is often set by capturing the gentle transit of rivers through the countryside (Figure 1.1). -2- Hickin: River Geomorphology: Chapter 1 View On The Stour Boatbuilding Near Flatford Mill Valley Of The Stour John Constable, English landscape painter (1776-1828) Bridge Over The Stour Flatford Mill The Hay Wain Figure 1.1: Examples of the landscape paintings of John Constable in which rivers and riverscapes form the central theme of his work. Closer to home we see fine examples of the work of the Group of Seven similarly engaged with rivers in various parts of Canada (Figure 1.2). Particularly relevant to us here in the lower mainland of British Columbia are Frederick Varley’s paintings of Lynn Creek (Moonlight at Lynn) and Cheakamus River (Cheakamus Gorge). Movies represent another visual-art form that have drawn significantly on rivers for subject matter. Examples that come readily to my mind include Apocalypse Now, The African Queen, Show Boat, A River Runs Through It, The River Wild, River of No Return, The Man From Snowy River and Wrath of God. TV movies of a more documentary nature include the 1999 movie Amazing Streams and Rivers (check it out at http://www.spout.com/films/155255/default.aspx). -3- Hickin: River Geomorphology: Chapter 1 A.Y. Jackson (1882-1974) The Red Maple J.E.H. MacDonald (1873-1932) Falls - Montreal River Frederick Varley (1881-1969) Cheakamus Gorge Frederick Varley (1881-1969) Moonlight at Lynn Tom Thomson (1877-1917) Woodland Waterfall Figure 1.2: Examples of river-themed paintings by the Canadian Group of Seven. -4- Hickin: River Geomorphology: Chapter 1 Poetry and music can also lay claim to rivers as artistic vehicles. You can compile your own list but at the risk of dating myself and making my ancient musical tastes public, my list of poems and songs would include ‘Banjo’ Paterson’s The Man from Snowy River, Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein’s ‘Ol Man River, Jimmy Cliff’s Many Rivers to Cross, and Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer’s Moon River. You can also check out another of my favourites: Alberta-born Joni Mitchell’s River at (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bVwo9IQMWM0) if you need to relax before moving to the next section dealing with rivers as hazards! She sees a river as an avenue of escape from life’s troubles: Oh I wish I had a river I could skate away on But it don’t snow here It stays pretty green I’m going to make a lot of money Then I’m going to quit this crazy scene I wish I had a river I could skate away on I wish I had a river so long I would teach my feet to fly Oh I wish I had a river I could skate away on I made my baby cry Before we leave this section on rivers and the arts we should note that rivers have been granted a quite special place in the Canadian identity through the activities of the Canadian Heritage River Board (CHRB). The CHRB was created to recognize the powerful part that rivers play in defining the Canadian landscape and in turn what it is to be Canadian. Examples of rivers declared by the CHRB to be special enough to be given heritage status in western Canada are shown in Figure 1. 3. The Fraser River was declared a heritage river in 1998. 3. Rivers as Hazards In contrast to the calm and soothing imagery of the riverscapes created by artists the reality is that many rivers are dangerous, every year taking thousands of lives and destroying property worldwide. Flooding is perhaps the most obvious river hazard. All natural rivers flood as part of their normal behaviour. It is by flooding that rivers build floodplains and in many places entire -5- Hickin: River Geomorphology: Chapter 1 Alsek River, Yukon Yukon River, Yukon Clearwater River, Saskatchewan South Nahanni River, NWT Kicking Horse River near Field, BC Fraser River, BC Figure 1.3: Examples of rivers in western Canada that have been declared heritage rivers by the Canadian Heritage River Board. ecologies are dependent on the regular seasonal overflowing of the channel to fill adjacent floodways and lakes. But humans also have a knack for building on floodplains and the results are often disastrous. We are all familiar with the tragic loss of life that occurs almost every year on the huge river systems (Jamuna, Padma (Ganges), Brahmaputra and Meghna rivers) draining the melting Himalayan snows and the rains from monsoonal and cyclonic storms across Bangladesh (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y9hw1V8YrFc) to the Bay of Bengal. But most places have rivers that flood and cause havoc. Here in BC Fraser River has a history of flooding its banks, sometimes just locally but also occasionally extensively enough to affect most of the Fraser Valley. One of the largest floods occurred in 1948, inundating much of the Fraser Valley (http://www.ec.gc.ca/water/en/manage/floodgen/e_bc.htm#1948) and isolating Vancouver for weeks (Figure 1.4). It was after this event that a system of dykes was built along much of the -6- Hickin: River Geomorphology: Chapter 1 Figure 1.4: The Fraser Valley town of Mission in flood in 1948 length of the Lower Fraser in order to contain a future flood of this magnitude. It is an interesting comment on our perception of hazards that flooding of the Fraser River is not seen today by politicians and planners to represent as much of a threat as history suggests. Yet little has changed since 1948, apart from the raising of barely adequate dykes and the construction of a dam on the Nechako River, a tributary that joins the Fraser River near Prince George. Essentially the flood of 1948 will be repeated in due course but in Vancouver we seem to be far more concerned about earthquakes that have never happened in hundreds of years than we are with what is almost a certain flooding disaster waiting to happen. Dyking rivers is the normal engineering response to coping with floods but they are not the simple fix as they might at first seem. Quite apart from the great expense of building them there is another problem. If the dyke is not high enough to contain a flood the floodwaters will surge onto the floodplain and be held back from rejoining the river further downstream because of – you guessed it – the dykes that line the river! This has happened many times during flooding on the Mississippi River and the US Army Corps of Engineers routinely in times of flood have to use explosives to create breaches in the dykes to let the water flow back into the river! -7- Hickin: River Geomorphology: Chapter 1 Scouring of bridge piers is another consequence of rivers in flood. Although most bridges today are designed to withstand a major flood the engineering design work required is not a precise science and bridges do continue to fail. Often associated with flooding on our local mountain rivers are debris flows, slurries of sediment and often large woody debris that move down the channel with such momentum that they are capable of knocking out bridge piers without first scouring the footings. A tragic example of this natural hazard is M-Creek on Highway 99 in Howe Sound. Here in 1981 a debris flow knocked out the bridge at night and ten people died as drivers of cars, unaware that the bridge had collapsed, drove into the channel. Excavation of building footings and buried structures (such as riverside buildings and pool foundations and sub-bed pipelines) by flood waters is also a widely reported destructive effect of flooding on all types of rivers. Erosion of riparian land by lateral migration is a related problem encountered mainly in river bends of meandering rivers. Such erosion of the outside (or concave side) of bends often takes Figure 1.4: These houses are the victims of lateral migration and undercutting by the Hope River in Tavern, St Andrew, taken two days after the passage of Tropical Storm Gustav on August 28, 2008. (Observer file photos). -8- Hickin: River Geomorphology: Chapter 1 out riverside roads (as happens frequently on Squamish River north of Vancouver). Again, the lateral migration of river bends in meandering rivers is entirely normal and can only be arrested by protecting the eroding banks by the emplacement of revetment (rip-rap) on the concave banks. This problem is exacerbated by developers who create housing projects on the edge of floodplains for that coveted “waterfront” status. Unfortunately waterfront on a migrating river is a rather dynamic concept (Figure 1.4)! 4. Rivers as Resources Rivers may have a hazardous and destructive side but they are also fundamentally one of our greatest resources. Rivers provide fresh water for many purposes: Domestic water use (drinking, cooking and washing) hardly needs explanation. In many parts of the world rivers are dammed to store water while elsewhere water is drawn directly from rivers for domestic water use. Rivers supply water directly or indirectly (from lakes) for urban gardens, pools and parks. Similarly, river water nourishes agriculture, sometimes being directly pumped to nearby fields and elsewhere being transported through pipes and aqueducts of irrigation schemes to distant fields. Industrial use of water can be rapacious and in most places depends on the availability of abundant river water. This connection is no more evident than here in British Columbia where pulp mills, for example, are always located near plentiful supplies of freshwater from rivers or lakes. Indeed, there are few industrial processes that do not consume large volumes of fresh water. Many regions draw their fresh water for domestic and industrial use from groundwater but this source is also dependent on water from rivers. Much of the water in the ground gets there by groundwater recharge from rivers on the surface. There is in fact an exchange of water that takes place between the groundwater and the river water. During dry periods river discharge declines and is sustained by groundwater seeping through the channel boundary to the river. During wet periods, on the other hand, the rivers fill and the elevated hydrostatic pressure forces water through the channel boundary to be stored in the ground below (in the aquifer). Hydro power is another obvious industrial dependency on river water. In British Columbia a number of our rivers are dammed so that the stored water can be used to drive the turbines in -9- Hickin: River Geomorphology: Chapter 1 hydro-electric generating plants. Indeed the Province is almost entirely dependent on rivers for its electricity and this dependency increases every year with the construction of the new lowhead run-of-the-river hydro power plants in the headwaters of mountain streams. The commercial and native fishery also depends on rivers. The health of salmon runs in particular is intimately connected to the health of our rivers and the role of rivers in the freshwater fishery is obvious. A related activity dependent on rivers is trapping. Of course trapping of fur-bearing animals is not the huge industry it was during historical times in Canada but trapping of beaver in particular remains an active enterprise in northern communities. Placer minerals are minerals that have been transported by the flowing water of rivers to depositional sites where they may be mined. In British Columbia and the Yukon the most important placer mineral is gold (alluvial gold) and it is found in the contemporary deposits of rivers and in older sediments such as those forming river terraces and abandoned channels. Elsewhere rivers have been the agent for transporting and concentrating alluvial diamonds. For example, the Orange River that separates South Africa from Namibia has transported diamonds from the interior kimberlites to the southwest coast of Africa where they were further concentrated by coastal processes to become what is today a commercially exploited very rich alluvial diamond field. 5. Rivers as Tourism and Recreational Assets Rivers attract tourists and have become increasingly important to the economies of many countries. Large rivers like the Mississippi, Nile, Rhone and the Amazon, for example, support fleets of high-priced tourist shipping while smaller more lively streams (like Squamish and Thompson rivers here in BC) have become ecotourism attractions or draw adventure tourists to white-water rafting and kayaking. Riverside parks are popular places (the lower Fraser River has many, for example) for camping and recreational fishing, boating and waterskiing or just simply river-watching. I’m sure that you can, with little difficulty, add to this list of riverside recreational activities. -10- Hickin: River Geomorphology: Chapter 1 6. Rivers as Transportation Corridors The role of rivers in the early exploration of Canada by the voyageurs needs no explanation to a student at Simon Fraser University! Rivers provided access to the interior of Canada and enabled the westward exploration of the country as the early explorers traveled the rivers by canoe to the coast. Today rivers continue to be important transportation corridors. Here in Canada rivers such as the Mackenzie in the North are critical for travel and commerce and rivers are used in the industrial centres as shipping routes. Much of Canada’s international trading is done by shipping that passes through the St Lawrence River in Quebec and Ontario in the east or through lower Fraser River in the west. In Canada rivers are used to transport log booms from the forests to the mills in many regions and barge traffic in most estuaries represent lifelines to coastal communities. All major roads follow river valleys. This correlation is particularly evident in the Coast and Rocky Mountains where highways and railroads cross the grain of the mountains via east-west river valleys. The route of the Trans Canada Highway (Highway 1) is dictated by the access provided by rivers such as the Fraser, Kicking Horse and Bow. Indeed the entire road system in British Columbia is laid out in river valleys. A river-dependent transportation issue that most of us likely do not think about is air travel! In mountainous areas such as western Canada recreational and small commercial aircraft follow routes over river valleys. Aircraft cannot fly above about 3000 m without oxygen being supplied to the cabin and this alone tends to limit routes to low-elevation passes (ie, river valleys). Weather is another factor: river valleys often provide an air route below the cloud ceiling. 7. Rivers as Habitat Rivers and their floodplains constitute one of the world’s great biosystems. It provides habitat for a huge range of animals and plants and most of the world’s birds, especially water fowl such as ducks and geese. Many river animals, like beaver, river otter, muskrat and mink were important commercial species and are historically important in Canada as the backbone of the early fur trade. Rivers are vital habitat to many species of fish, of course none more important -11- Hickin: River Geomorphology: Chapter 1 than salmon and trout here in Canada. Even mammals such as beluga whales that we usually associate with the oceans come into estuaries of rivers like the Mackenzie to calve. Other animals most of us will readily associate with rivers include moose, bear, caribou and elk. In BC the gathering of salmon and eagles on Squamish River has become an annual celebration! 8. Rivers as Legal Boundaries Again, not something most of us think about but rivers in many parts of the world are used as legal boundaries. At a local level rivers can form municipal and county boundaries such as the Capilano River that separates West and North Vancouver or the Squamish River that defines one of the boundaries of the Squamish Nation Reserve in Squamish. In North America many Provincial and State boundaries are defined by river courses. For example, in Canada, Quebec and Ontario share a boundary on the Ottawa River. In the US a number of states (for example, Minnesota/Wisconsin, Iowa/Wisconsin, Iowa/Illinois, Missouri/Illinois, Illinois/Indiana, Indiana/Kentucky, Arkansas/Tennessee, Arkansas/Mississippi, Louisana/Mississippi, among others) have borders formed by the Mississippi/Missouri system rivers. Rivers forming international borders include the St Lawrence (Canada/US), the Rio Grande (US/Mexico), the Putumayo River (Colombia/Peru), the Mekong River (Burma/Thailand/Laos), the Orange River (Namibia/South Africa), the Amur River (Russia/China), the Oder River (Germany/Poland) and the Rhine River (France/Germany), among many others. One of the interesting problems that arises from using a river course to define a legal boundary is that rivers move so there is a question about what that means for the boundary! For example, in the case of the US and Mexico, the border between the two countries is defined by a very mobile Rio Grande River and this has led to the establishment of the International Boundary and Water Commission whose mandate includes monitoring the position of the Rio Grande River and resolving the resulting territorial disputes (http://www.ibwc.state.gov/home.html). A principle well established in law now is that legal boundaries move with rivers if the channel migrates incrementally (gradually) over time but are left behind if the channel moves by avulsion (catastrophically). As you can imagine, this arbitrary legal principle creates as many problems as it solves! -12- Hickin: River Geomorphology: Chapter 1 9. Rivers as Geomorphic Elements and Agents This brief survey of the importance of rivers brings us to the matter at hand: the role of rivers in making and shaping the landscape. Most of the earth’s surface consists of the nested basins (drainage basins) that accommodate and supply rivers with water and sediment. Indeed, drainage basins are regarded by most geomorphologists as the fundamental geomorphic unit. Even in glaciated landscapes and in deserts, rivers and their valleys are the dominating landscape element. It is fair to say that, almost everywhere on the land, rivers represent the most important set of processes shaping the surface of the earth. In the long term (millions of years) they undertake the surface erosion (Figure 1.5) that balances the creation of new land by tectonics A C B Figure 1.5: The erosive power of rivers is clearly evident on Fraser River at Hell’s Gate (A), on Lilloett River near Pemberton BC (B) and on the Athabasca River in the Canadian Rockies (C). -13- Hickin: River Geomorphology: Chapter 1 (uplift) and therefore are integral in the processes that maintain crustal equilibrium and mass balance. Rivers transport to oceans the water and sediment eroded from the continental highlands. They form a central element of the hydrologic cycle (Figure 1.6). They are like a global system of geomorphic conveyor belts moving water and sediment from the mountains to Figure 1.6: Rivers are important components of the hydrologic cycle. the sea. In the shorter term they create valleys and build floodplains and they build deltas that store sediment eroded from the continents (Figures 1.7 and 1.8). A B Figure 1.7: Deltas are sites where rivers store sediments transported from the continental highlands. A: Buchan’s Brook delta in Red Indian Lake, Newfoundland, and B: the bird’s foot delta of Scotts Brook, Cape Bretton Island. -14- Hickin: River Geomorphology: Chapter 1 Figure 1.8: The Fraser River delta at Vancouver, British Columbia. 10. The River System One of the important principles that you will have encountered in earlier courses is that rivers form a part of the interrelated environment that we sometimes refer to as the earth system. But here we need to recognize that rivers themselves are part of a smaller nested system that also functions as an interdependent set of forms and processes; geomorphologists have named this the fluvial system. The fluvial system is a concept that draws our attention to the fact that rivers are complex and form part of a dynamic system in which all parts are interdependent. This notion is captured in the diagram of relationships described in Figure 1.9. This diagram is from David Knighton’s book Fluvial Forms and Processes (1998) and you will find it a useful place to revisit as we continue our exploration of the ways of rivers. -15- Hickin: River Geomorphology: Chapter 1 Figure 1.9: “The fluvial system” from Knighton (1998: Figure 1.1). Knighton’s diagram recognizes that all aspects of river channel morphology (for example, channel slope, width, depth and planform character) and flow (velocity, for example) are related and that they, in turn, depend on several independent channel controls (such as valley slope, river discharge, input of sediment, and bank material type and strength). These channel controls are in turn dependent on basin controls such as physiography, vegetation and soils which in turn ultimately depend on regional climate and geology. We do not fully understand the details of many of the processes that control these relationships but most geomorphologists have no doubt about the existence of such complex interdependencies even if we have yet to fully specify them. One of the important implications of this diagram of the fluvial system is that, if one or more components change, many others will be affected in some way. Local changes (such as building a dam and diverting water from the basin) will set in motion changes in the rest of the system. The more general the change (such as a shift in climate) the more profound will be the impact on the fluvial system. Some of you may not be surprised at the nature of these interdependencies but most of us would be surprised to -16- Hickin: River Geomorphology: Chapter 1 learn how often they are ignored by planners and engineers and geomorphologists responsible for managing our rivers. 11. Some Further Reading At this early stage in our discussion of fluvial processes you might find it most useful to consult a general textbook on geomorphology and refer to the chapter(s) on rivers and fluvial geomorphology. Three good sources in the Library are Easterbrook (1999), Ritter et al (2002) and Trenhaile (2006): Easterbrook, D.J. 1999 Surface Processes and Landforms, Prentice Hall. Ritter, D. F. Kochel, C. and Miller, J.R. 2002 Process Geomorphology, Waveland Press. Trenhaile, A.S. 2006 Geomorphology of Canada, Oxford University Press. More advanced (but less readable) accounts are the introductory chapter in Knighton (1999) and Richards (1982): Knighton, D. 1998 Fluvial Forms and Processes: A New Perspective, Hodder Arnold Publication, Chapter 1. Richards, K.S. 1982 Rivers: Forms and Processes in Alluvial Channels, Blackburn, Chapter 1. The SFU Library has both of these advanced texts. 12. What’s Next? Now that we have finished our preamble on rivers we can get on with the next step of getting down into the river channel to see what makes it tick! What is it that determines the size of a river and how do we measure it? These are some of the basic questions of fluvial geomorphology and are the subjects of Chapter 2. -17-