Case Studies of Transportation Investment to Identify the Impacts on the

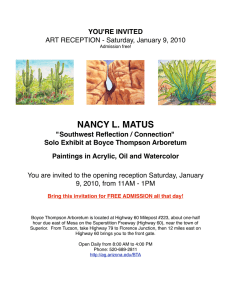

advertisement