WOMEN, GIRLS AND DISASTERS A review for DFID by Sarah Bradshaw

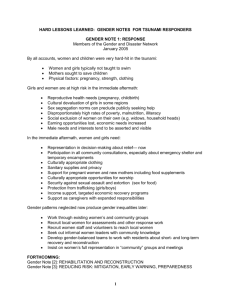

advertisement