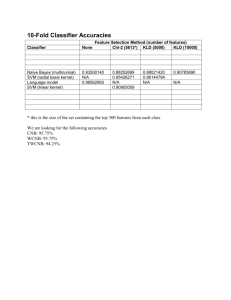

How Well Do Social Ratings Actually Measure Corporate Social Responsibility? A K. C

advertisement