Rhetorical Structure Theory: looking back and moving ahead

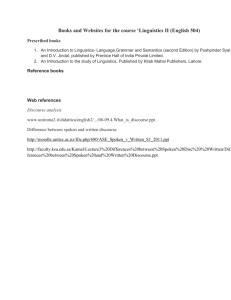

advertisement