ZEF Bonn Migration due to the tsunami in Sri Lanka -

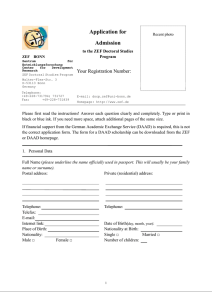

advertisement