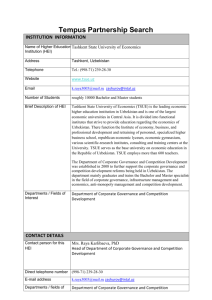

“Knowledge Management in Rural Uzbekistan:

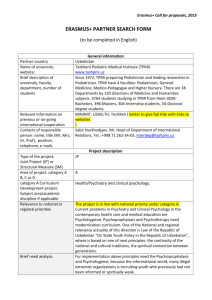

advertisement