An Examination of New York State’s Integrated Primary and Mental Health

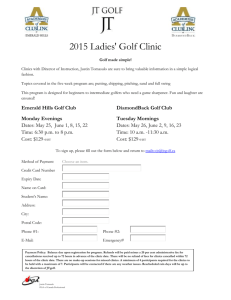

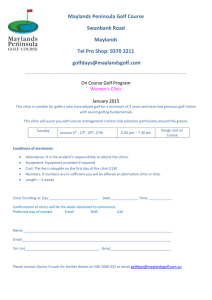

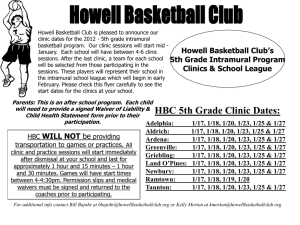

advertisement