Evaluation of Emergency Education Response for Syrian Refugee Children and

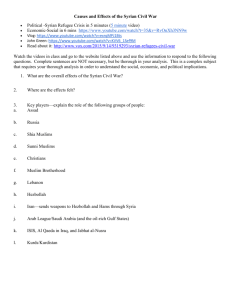

advertisement