Market Integration in the Chinese Beer and Wine Markets: Evidence from Stationarity Test 3 CHAPTER

advertisement

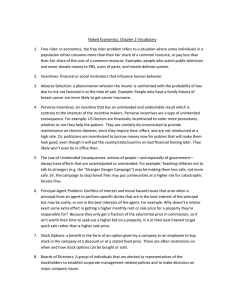

Seediscussions,stats,andauthorprofilesforthispublicationat:http://www.researchgate.net/publication/282862403 MarketIntegrationintheChineseBeerand WineMarkets:EvidencefromStationarityTest CHAPTER·OCTOBER2015 READS 3 4AUTHORS,INCLUDING: ChiKeungMarcoLau ZhibinLin NorthumbriaUniversity NorthumbriaUniversity 43PUBLICATIONS89CITATIONS 11PUBLICATIONS3CITATIONS SEEPROFILE SEEPROFILE DavidBoansi UniversityofBonn 16PUBLICATIONS18CITATIONS SEEPROFILE Availablefrom:ZhibinLin Retrievedon:17October2015 Market Integration in the Chinese Beer and Wine Markets: Evidence from Stationarity Test Marco Chi Keung Lau1*, Zhibin Lin1, David Boansi2, Jie Ma1 1. Newcastle Business School, Northumbria University, City Campus East, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE7 7QP United Kingdom. 2. Department of Economic and Technological Change Centre for Development Research (ZEF), Bonn, Germany. *corresponding author: chi.lau@northumbria.ac.uk To cite this article: Lau, M. Lin, Z, Boansi, D. & Ma, J. (forthcoming). “Market Integration in the Chinese Beer and Wine Markets: Evidence from Stationarity Test”, in Ignazio Cabras, David Higgins, David Preece (eds), Brewing, Beer and Pubs: A Global Perspective, Palgrave Macmillan. Abstract Following the economic reform in China and subsequent economic growth, the country has witnessed interesting shifts in dimensions of supply in various subsectors. This has in one way or another, stimulated growth in national and per capita disposal incomes among other economic indicators. In particular, there has been rapid growth in both beer and wine consumption in the country. This chapter aims to examine the nature of the beer and wine industry. Specifically we investigate price related issues and the degree of integration of the Chinese beer and wine markets and the nature of price convergence/divergence across major markets. The study utilises a 10-day interval data of beer and wine retail prices from January 2005 to December 2012 provided by the National Development and Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China. A series of unit root tests are performed to assess the price convergence. The empirical findings suggest that Chinese beer and wine markets are not well integrated, and there is no evidence of significant arbitrage activities in the wine and beer markets. Implications for policy development were discussed. 1 Introduction Prior to the economic and market reform, China was a relatively closed society and had faced economic stagnation mainly due to the excessive centralised bureaucratic control (hence misallocation of both investment goods and outputs and low total factor productivity). Initiated in the late 1970s, the reform was set out to make the country wealthy and powerful through reducing (but not eliminating) level of centralised planning and direct control to correct the economic deficiencies (Perkins, 1988). In the late 1970s, Chinese households had to do with barely sufficient food supplies and rationed clothing. At the turning point at the “Third Plenum of the National Party Congress’s 11th Central Committee” in December 1978, the central government decided to undergo gradual economic reforms. On of the most fundamental reforms occurred in the 1980s and was aimed at converting the command economy to a price-driven market economy, diluting the influence of the state in resource allocations. This goal was achieved with the dual-track pricing system, in which some goods and services were allocated at state controlled prices (e.g. energy products), while others (e.g. consumer goods) were allocated at market prices1. One direct outcome of that was the change of the country’s Soviet-type, centrally planned system into a market-oriented system. The reform began cautiously in 1979 with agricultural production in rural areas (to institute a household responsibility system which allows formers to sell their surplus crops), and later expanded to urban industries (to create special economic zones and welcome the establishment of Sino-foreign joint ventures for advanced production technology and management knowledge). These changes have had significant effects on agricultural and industrial production and productivity (Fan, Wailes, & 1 Almost all goods were allocated at market prices by the early-1990s. 2 Cramer, 1995). They have also helped the country gradually open its market to foreign investment and expand its trade with the rest of the world. In the 1980s, the country continued the reform and its economic landscape have changed dramatically. A new wave of the economic liberalization (e.g., to open more cities and regions in the coastal provinces and became a member of the International Monetary Fund and Wold Bank) has strongly advocated the country’s market and globalization policies such as decentralization, privatisation, free trade, free investment, and deregulations (Su, 2011). In the following decade, more market-oriented and preferential policies (e.g., tax concession and labour mobility) were given to the coastal provinces to boost foreign investment. The benefits of these policies can be highlighted by the increasing international trade and sub-regional economic cooperation between coastal provinces and neighbouring countries. Until more recently, the country has maintained strong ties with the international market. In particular, following the accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, many remaining trading restrictions were removed (i.e., eliminate price protection to domestic industry and eliminate export subsidies on agricultural products). During the first decade of the 21th century, other economic and governance infrastructure has also been reformed, such as opening share markets to foreign investors, the open market agreement with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the ASEAN + 3 (China, Japan, South Korea) trade framework (CSIS, 2015). Following the reform, the country become more integrated into the global capitalism system and has enjoyed a historically subsequent economic growth. In addition, with trade liberalization and restructuring of economic, social and geo-political/regulatory environments come development in various supply indicators, including production, imports, exports, consumption and most importantly retail prices. Obviously, over the last thirty years, the country has witnessed interesting patterns/shifts in the aforementioned dimensions of supply 3 in various subsectors, and this has in one way or another stimulated growth in national and per capita disposal incomes among other economic indicators. Several drivers have steered trends and recent growth in the beer and wine markets, which include: improvements in disposal income in both the urban and rural economy (hence purchasing power) (Bouzdine-Chameeva, 2013; Swinnen, 2011), increasing migration (Zhao, 2003; Huang and Rozelle, 1998; Huang and Bouis, 1996), perceived gender-related health benefits of beer and wine compared to spirits (Stone, 2014), stronger retail supply networks (Access Asia Limited, 2010), developments in relative price of alcoholic beverages and strong competition (Cui et al., 2012). Since the 1980s, both on-trade2 and off-trade3 consumption of beer and wine in China have been increasing (Cui et al., 2012), with major surges being noted in the last decade (since the year 2003). From average beer and wine consumers by rank during the 1960s to 1990s, since the year 2003 China has become the largest beer market (volume-wise) in the world (Swinnen, 2011), the largest red wine market in the world (Stone, 2014; Chow, 2014), and fifth in rank among the major wine consuming nations. Besides this, the country is now the World’s fifth-largest producer of wine (Stone, 2014) and approximately 83 percent of wine consumed in the country between the years 2007 and 2013 was produced domestically (Chow, 2014). Although China has a rich alcoholic drinks history, especially when compared to other spirit drinks, i.e., rice wine, the consumption of beer and grape wine in the past was relatively low and undifferentiated (Jenster and Cheng, 2008). Modern Chinese beer brewing and grape wine-making can only be dated back to around 100 years ago, when modern brewing technology was introduced to China in the late 1890s (Liu and Murphy, 2007). As the demand grew by the foreign workers and soldiers, some foreign-invested and local Chinese breweries/wineries started to emerge in some eastern cities of the country to serve the 2 3 On-trade consumption of beer and wine refers to purchase and consumption of beer and wine sold in restaurants, bars, etc Off-trade consumption of beer and wine refers to purchase and consumption of beer and wine sold in retail stores 4 colonial powers (Heracleous, 2001). The few early beer breweries and wineries included the ChangYu Winery in 1892, Russian’s Ulubulevskij Brewery (later Harbin Brewery) in Harbin in 1900, the German and British’s joint-venture Germania-Brauerei Brewery and Winery (later Tsingtao Brewery) in Qindao in 1903, the Scandinavia Brewery in Shanghai in 1910 and the TongHua Winery in Jilin in 1912. However, prior to the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the growth of the production was modest (Li, 2011) and even ground to a halt because of the two world wars. Hence, the prices were high and the beer and wine were mainly produced to serve the needs of expatriates and Chinese national bourgeoisie (Bledsoe, 2011). In 1949, after the PRC was founded, a new stage of the modern Chinese beer and wine industry began in the early 1950s and lasted over 25 years until the late 1970s. At this stage, all breweries and wineries were confiscated and turned into stateowned enterprises. The development of the whole alcoholic drinks industry was largely neglected as the beer/wine was treated as a non-essential consumer product in the country’s industry restructuring. Despite the efforts by the government to rehabilitate the industry in the late 1950s, the beer and wine production remained small-scaled and underdeveloped (Jenster and Cheng, 2008). From the mid 1960s, some small-scaled breweries were created and the production was gradually increased. Until the late 1970s, these breweries/wineries were remained state-owned and the price were controlled and set by the government. From the 1980s, as a result of economic reform, the Chinese alcoholic drinks industry had recorded an intensive growth in production. In the following three decades, the industry underwent substantial development. Many state-owned breweries have been privatised (e.g., Harbin Brewery, Tsingtao Brewery, etc.) and price controls lifted. One of the most important economic reforms is the commodity price reform. The sign of price convergence across different geographical locations is a pre-requisite for efficient resources allocations and hence proper functioning of free market economy. In Chinese beer 5 and wine market we expect price convergence across cities because of several reasons. First the entry of foreign brewers increase competition and the market structure moved towards a perfectly competitive market, resulted in more arbitrage activities and price convergence. Secondly liberalization of State Ownership Enterprise (SOE) allowed for heterogeneous enterprise ownership forms including joint-venture and private ownership. This again resulted in more arbitrage activities and price convergence. Another advance in the process of marketization is the introduction of the Labour Contract System in 1986. The reform enabled breweries to explore profit opportunities and enhance arbitrage activities by having greater autonomy on sourcing of raw materials, setting selling prices, recruiting employees, and changing wages within the enterprise. Price convergence is thus expected due to a more efficient market across different cities. Nevertheless, interregional development and income disparity and the persistent interregional trade barriers within China may inhibit such price convergence. Following post-reform developments in China, total consumption of beerincreased by 66.76 percent between the years 2003 and 2009 (Access Asia Ltd, 2009). This percentage increase represents an increase in absolute volume from 24.30 billion litres to approximately 42.19 billion litres. This reflects annual percentage growth rate of 7.584 percent between the two aforementioned years. With these, the country witnessed a 6.66 percent annual growth in per capita consumption of beer, as per capita intake increased from 19.64 litres in the year 2003 to 30.84 litres in 2009 (representing an increase of 57.03 percent between the two years). Compared to less than 1 litre of beer consumed by the average beer consumer in China during the years 1979 and 1980 (Swinnen, 2011), beer consumption per capita in the country 4 Average percentage growth= 100*(<final value> / <initial value>)^(1/<number of years covered>) - 100 6 is noted to have increased by approximately 30 times as of the year 2009. Although well above the 2010 per capita beer consumption of less than 2 litres in India for example, per capita beer consumption in China is still well below per capita consumption levels in the US and Western and Central Europe (e.g. 156 litres per capita in Czech Republic, 130 litre per capita in Ireland, and 116 litres per capita in Germany) (Swinnen, 2011). The relatively lower per capita beer consumption in China, in spite of its role as the leading beer consumer in the world, presents a major growth potential of the country’s beer market to both domestic and foreign producers. The observed developments in total and per capita consumption of beer in China between the years 2003 and 2009 triggered a 125.02 percent (in current value terms) and 120.39 percent (in constant terms, with 2002 as base) increase in total expenditure on beer. Total expenditure rose from RMB138.99bn to RMB312.77bn (in current terms) and from RMB139.27bn to RMB306.94bn (in constant terms) between the years 2003 and 2009. Total per capita expenditure on beer rose in current terms from RMB107.93 in the year 2003 to RMB228.64 in the year 2009. In constant terms, these values were RMB108.14 and RMB224.38 respectively for the years 2003 and 2009 (Access Asia Ltd, 2010). Over the period 2003 to 2009, retail sales accounted for 66.53 percent of total volume consumed and 51.56 percent of total expenditure on beer. HoReCa (Hotel, Restaurant, and Catering/canteen) sales accounted for 33.47 percent of total volume consumed and 48.44 percent of total expenditure on beer over the aforementioned period. Beside the escalations noted in the Chinese beer market, total and per capita wine consumption in China increased respectively at average annual growth rates of 17.92 percent and 17.90 percent between the years 2005 and 2012. Total volume of wine consumption increased from 45.60 million 9-litre cases (Bouzdine-Chameeva et al., 2013) in the year 2005 7 (equivalent to 0.55billion bottles5) to 170.50 million 9-litre cases in the year 2012 (equivalent to 2.05 billion bottles). This represents an increase in wine consumption of 273.94 percent between the years 2005 and 2012. Along these developments in total wine consumption in the country, per capita consumption increased from 0.3 litres in the year 2005 to 1.12 litres in 2012 (representing an increase of 273.33 percent). By this, total and per capita wine consumption as of the year 2012 were almost 4 times the 2005 consumption levels. A recent study by Vinexpo and IWSR (International Wine and Spirits Research), as cited in Lodge (2012), reveals that wine consumption per person in China is anticipated to further increase, reaching 2 litres by the end of the year 2015. French and Italian consumers are expected to consume 50 litres per person per year, while consumers in the US are expected to on average consume 13 litres per person per year. Current surges and anticipated increments in future wine consumption in China are founded on increasing consumer preference for red wine over other alcoholic beverages and developments in price of various types of wine across major markets. In contrast, a respective decline of 18 percent and 5.8 percent in France and Italy, red wine consumption in China is reported to have almost tripled between the years 2007 and 2013. Although well below the 51.9 litre average recorded for France, per capita wine consumption in China is reported to have increased from the 2012 figure of 1.12 litres to 1.5 litres in the year 2013 (Chow, 2014) (representing an increase of 33.83 percent between the two years). These developments in both beer and wine consumption have attracted greater investment attention from domestic and foreign investors, who seek proper exploitation of the opportunities presented by recent and anticipated developments in the Chinese beer and wine industry. To enter into and succeed in the industry however, besides seeking ways to please the consumers, there is a need to better understand the complex Chinese beer and wine 5 Computed by authors using a conversion factor of 83.35, thus number of bottles (billion) = total volume (million 9-litre cases) /83.35 8 markets, as relevant characteristic of such markets (most importantly developments in price) vary from region to region. Such information is vital not only in aiding assessment of the efficiency and effectiveness of beer and wine markets, but also in making informed investment decisions on which markets have the potential to yield significant profits for investors based on the heterogeneous objectives of investors. Investigating the level of integration of the retail market on beer and wine across regions in the largest transitional market of China is the primary objective of this study. This is to help inform agribusiness investment decisions on effectiveness of the Chinese beer and wine industry, and to guide exploitation of current and future opportunities presented by the industry. China’s increased disposable income and rise of middle class allowed many consumers to afford foreign-made and foreign-branded alcoholic beverages. It’s important for both domestic and foreign companies to understand the marketization status of different cities in face of changing regulatory environment. The distinguishing feature of our study is that it allows us to identify which cities are more competitive and integrated. 9 Literature Review Under regularly assumed restrictions on preferences and technologies, a competitive market equilibrium exists (Ravallion, 1986). In general, this also holds for the spatial competitive equilibrium of an economy consisting of a set of regions among in which trade occurs at fixed transport costs. Such equilibrium has the property that, if any trade takes place between any two regions, price in the importing region equals price in the exporting region plus the unit transport cost. Under this circumstance, the markets can be said to be spatially integrated. Market integration can thus be defined as the extent to which changes in prices within one market lead to changes in prices in another. In other words, differences in the prices of a given product across regional markets can be interpreted as a signal of the degree of market integration in a general equilibrium sense: a shortage in one regional market increases the price, which then attracts suppliers from neighbouring markets (Gibson, 1995). The resultant increase in supply in one market and increases in price in source markets continues until differentials are eliminated, net of transport cost differentials. In an integrated market, products flow away from locations where the price is low and towards locations where the price is high. These flows enforce the Law of One Price. Any factors that affect trade between markets affect market integration, for example trade costs, trade barriers and price discrimination (Yu, Lu & Luo, 2013). The cost of arbitrage plays an important role in determining the degree of market segmentation (Lutz, 2004) Zhou, Wan, and Chen (2000) suggested that access to price information and availability of transport are the most stressed exogenous factors affecting price behaviour. Related to transport which is the distance between markets. Distance, in principle, should not be an obstacle to market integration, though it affects the speed of market integration. In international markets, there are three major sources of price discrimination across national boarders, i.e. demand elasticity, import quota and collusion – which affect international 10 pricing (Verboven, 1996). Within a domestic market, the regional differences in demand (income effect) and supply (competition effect) are the major factors that affect price integration (Yu et al., 2013). The existing literature on market integration in China show mixed and inconclusive results. Young (2000) argues that although twenty years of economic reform have brought extraordinary economic growth and burgeoning international openness, it has also resulted in a fragmented internal market, due to the rise of local protectionism. Based on five fairly aggregated sectors, he finds that prices of goods diverged and resource allocation were deviated from the principle of comparative advantage. Zhou et al. (2000) analysed the rice markets in southern China using the monthly prices of indica rice from 35 major cities with the time series extends from February 1992 to May 1996. Their results show that there is a general lack of integration among the indica rice markets in China. They suggested that the poor transport facilities, government interventions, and the limited amount of grain available for arbitrage as the major impediments to market integration. Poncet (2005) examined the industry-level domestic trade flows between Chinese provinces to measure domestic market integration in China in 1992 and 1997. The results show international trade barriers dropped but domestic trade barriers (between provinces) increased, underlining the fragmentation of the Chinese domestic economy and even the spread of local protectionism over the period. The author concluded that rather than a single market, China appears as a collection of separate regional economies protected by barriers, which include a variety of protectionist policies, such as regulatory, physical and judicial obstruction (Young, 2000). Poncet’s (2005) study confirms that provinces’ domestic trade protection pursues a dual objective of socioeconomic stability preservation and fiscal revenues maximization. Gravier-Rymaszewska, Tyrowicz, and Kochanowicz (2010) analysed the effects of intra-provincial disparities on the development of the 28 mainland provinces in China and found that while the growth in China 11 increases, the difference in wage levels in each sector along with the inequality is also rising. They concluded that prices in China did not reflect the relative scarcity of goods. However, Chen, Goh, Sun, and Xu (2011) suggested that the past three decades have witnessed a high level of domestic market integration in China, which include various dimensions such as urban agglomeration, rural­urban migration and integration on the labour, product, and capital markets. They argue that particularly for the product markets, which have become significantly more integrated, as regional trade increased and product prices became more similar across regions. Chen et al. (2011) argue that there has been emerging evidence of increasing integration of China’s internal markets of goods and commodities. Chen et al. (2011) argued that evidence based on more refined data supports increasing regional specialization and product market integration over time. Holz (2009) argues that there is evidence to support that China has seen an increasingly integrated domestic product market, which is well within the range of that of a normal, relatively integrated large economy. Similarly, Huang, Rozelle, and Chang (2004) found high degrees of integration between coastal and inland markets and between regional and village markets in China’s agricultural sector, since its accession to the World Trade Organization. Nagayasu and Liu (2008) examined the relative prices and wages in China based on the annual data of the 29 provinces in China from 1995 to 2005 and reported a strong evidence of non-divergence in the prices of provinces vis-a-vis those of the benchmark (Beijing). Given the mixed and inconclusive results, in the next section of our paper we investigate this effect using advanced empirical strategy, which is based on sound theoretical base to find out if prices on beer and wine products have converged across Chinese regions. Allocative efficiency in the goods market is an important outcome of market liberalization. China becomes one of the largest consumer markets for alcoholic drinks but its allocative efficiency has not been examined. Therefore we provide the first attempt in investigating how 12 well the retail market on beer and wine has been integrated across regions in the largest transitional market of China. Our study on market effectiveness is based on the economic theory of “Law of One Price” in an efficient market. The concept was developed by Gustav Cassel in 1920 saying that, identical goods should converge to one price across regions due to the force of “arbitrage activities”. Gibson and Smout (1995) argue that a reduction in price differential between regional markets, until they represent nothing more than transport cost differences represents an efficient market condition. However the existence of trade barriers (i.e. lack of infrastructure or heterogeneous policies) and imperfect market structure may result in price divergence across domestic markets. 13 Data and Results We utilize a 10-day interval data from January 2005 through December 2012, and the data collected from the Price Supervision Centre under the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) of the People’s Republic of China (PRC)6. Our data covers domestic consumed beer and domestic consumed wine. Data was collected at 10-day intervals respectively at 5th, 15th and 25th of each month. We have 250 observations per city on average. Firstly, we construct relative price series towards the national average price, so that the series of interest for a particular alcoholic product in city i, at time t, is g , we have g yi ,t ln i ,t g t Where yi ,t t= 1,…,T is the relative price series, (1) g i ,t is the price level, and gt is the average price level across all cities at time t. Wine becomes popular in China, we can see from Table 1 that the average price for wine was RMB36.6 per bottle from 21, January 2006 to 01, November, 2010, and the mean price difference was -0.085 (see Figure 3, Panel A). The price for wine in most cities is lower than the national average price. (see Figure 4, Panel A) The price for beer is about RMB2.98, and the price variation across cities is lower than that of wine. (see Figure 4, panel B). The price for beer in most cities is lower than the national average price. (see Figure 4, panel B). To our best knowledge our data set is the first attempt to cover 141 cities to provide robust study (Detailed cities names are provided in appendix). The econometrics method we use is “unit root test”. This applied econometrics test plays an important role in mainstream economics research as it was developed by Dickey and Fuller (1979) 7, numerous surveys and studies introduced this method since then (see, Perman,1991; Campbell and 6 For details: http://www.chinaprice.com.cn/fgw/ProxyServlet?server=e450&urls_count=1&url=info/S_0_0_0_0.htm 7 The article received 4322 citations from different social science disciplines since its publication. http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=zh-CN&q=Dickey+and+Fuller+%281979%29&btnG=&lr= 14 Perron , 1991; and Dolado et al., 1990). Several important topics in economics and finance adopt unit root test, including purchasing power parity, unconditional income convergence hypothesis, and financial market bubbles, corporate profit persistence, financial leverage mean reversion, and price convergence. Unit root test is used to test for the stationarity of a time series. As many time series, for example beer price may fluctuate in the short run after an external shock of increase in import tax. However the price fluctuation will stop eventually, we call this time series “stationary” if it exhibits these characteristics of “stationarity”. Otherwise the data set was said to contain a “unit root”. We can use this terminology to examine if two cities show evidence of price convergence by applying unit root test to their relative price. If the relative price exhibits stationarity behaviour then price convergence is evident. 15 Panel A: Price for Wine 2,000 Series: Price Sample 1/21/2006 01/11/2010 Observations 7562 1,600 1,200 800 Mean Median Maximum Minimum Std. Dev. Skewness Kurtosis 36.62361 33.30000 162.0000 7.800000 18.11915 3.538451 23.11738 Jarque-Bera Probability 143297.2 0.000000 400 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 Panel B: Price for Beer 2,000 Series: Price Sample 1/11/2005 5/01/2009 Observations 8515 1,600 1,200 800 Mean Median Maximum Minimum Std. Dev. Skewness Kurtosis 2.985728 2.910000 7.000000 1.100000 0.990329 1.307192 5.365741 Jarque-Bera Probability 4410.677 0.000000 400 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 16 7 Panel C: Price Difference for Wine 1,200 Series: Price Difference Sample 1/21/2006 1/11/2010 Observations 7562 1,000 Mean Median Maximum Minimum Std. Dev. Skewness Kurtosis 800 600 400 200 -0.085081 -0.086085 1.550105 -1.572147 0.402699 0.081726 5.703972 Jarque-Bera Probability 2312.139 0.000000 0 -1.5 -1.0 -0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 Panel D: Price Difference for Beer 800 Series: Price Difference Sample 2/21/2005 6/01/2009 Observations 8515 700 600 Mean Median Maximum Minimum Std. Dev. Skewness Kurtosis 500 400 300 200 Jarque-Bera Probability 100 0 -1.0 -0.8 -0.6 -0.4 -0.2 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 17 0.8 -0.047754 -0.045724 0.932856 -0.980119 0.304882 0.241648 3.421045 145.7675 0.000000 Figure 1: Summary Statistics Panel A: Wine Price Difference .4 .2 .0 -. 2 -. 4 -. 6 -. 8 I II III IV I II 2006 III IV I II 2007 III IV I 2008 M ean II III IV 2009 I 2010 + / - 1 S . D. Panel A: Beer Price Difference .4 .3 .2 .1 .0 -. 1 -. 2 -. 3 -. 4 -. 5 I II III 2005 IV I II III IV I 2006 II III IV 2007 M ean +/- 1 I II S . D. Figure. 2: Mean and Standard Deviation of Price Difference 18 III 2008 IV I II 2009 Univariate Unit Root test A rigorous assessment regarding price convergence across Chinese markets can be carried out through a univariate unit root test and panel unit root test8. Panel A of Table 1 presents unit root tests of relative price series for Wine using evidence from 105 Chinese cities. Of the 105, only 11 cities or 10.5% of the total number showed price convergence for wine. For Beer, the convergence rate is much lower. Only 5 cities or 3.5% of cities showed evidence of price convergence. Based on these results, we can therefore conclude that Chinese alcoholic markets are not well integrated, and there is no evidence of significant arbitrage activities in the wine and beer market. It is possible that significant transaction cost, internal trade barriers, and imperfect market structure exists. Robustness check: Panel Unit Root Test Bearing in mind the criticism laid in literature against univariate unit root test of lacking statistical power, we made use of several panel unit root tests to check robustness of our results. The outcome is presented in Table 2. The empirical finding suggests that there is a general lack of evidence for price convergence for wine and beer market. This finding is in line with a previous study, in which, the authors concluded that non-perishable consumer goods have the lowest rate of convergence amongst all other consumer goods in China (Fan and Wei, 2006). Existing convergence literatures are also interested in the degree of local protectionism or market structure in other industries, for example, textiles, automobile, and gasoline sector. For the Russian textiles sector there is strong evidence in favour of market integration and hence less hidden trade barriers in the domestic market (Lau and Akhmedjonov, 2011). This finding suggests that textile market is efficient in Russia attributed to a better regulation and institutional arrangement with anticipated WTO accession. In 8 Interested reader should consult the literature on unit root test (see for example: Campbell and Perron, 1991; Dicky and Fuller, 1979; Levin, Lin & Chu 2002; Im, Pesaran and Shin 2003; Maddala and Wu, 1999). 19 another study that focuses on the automobile market in the European Union over the period 1995 to 2005, the authors found that exchange rate uncertainty is the cause of price divergence across EU countries. And they concluded that trade liberalization is the key determinant for regional integration in the long run (Gil-Parej and Sosvilla-Rivero, 2008). Finally, a study explored the price convergence mechanism in the Canadian retail gasoline market since 2000, and it concludes that the internal market is well integrated, even in face of the fuel prices regulation in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, which may potentially distort the national gasoline market. The robust evidence of lacking price convergence on the beers and wine market indicates that the alcoholic consumer market still remains as a collection of separate regional markets protected by barriers rather than a single market. And this empirical finding poses the question of whether new business ventures entering the domestic market could earn abnormal profit and capture market share. Therefore further research is needed to examine the determinants of price convergence in the beers and wine market in China. 20 Table 1: Univariate Unit Root Test of Relative Price Panel A: Wine (Evidence based on 105 Cities) City Probability Value Significance Conclusion 0.0002 *** Converging to the national mean price Mianyang 0.0907 *** Converging to the national mean price Yinchuan 0.0083 *** Converging to the national mean price Yantai 0.0532 ** Converging to the national mean price Jinzhou 0.011 *** Converging to the national mean price Beihai 0.0196 *** Converging to the national mean price Jilin 0.0128 *** Converging to the national mean price Nanjing 0.0511 ** Converging to the national mean price Luoyang 0.0252 ** Converging to the national mean price Tai'an 0.0076 *** Converging to the national mean price Tonghua 0.008 *** Converging to the national mean price Anshan Number of instances of convergence 11 cities or 10.5 percent Note: Null hypothesis is that each relative price series contains a unit root. ***and ** denote 1% and 5% significance level respectively. Panel B: Beer (Evidence based on 141 Cities) City Probability Value Significance Xiamen 0.0006 *** Shanghai 0.0152 *** Dalian 0.0452 *** Anqing 0.0142 ** Xingtai 0 *** Number of instances of convergence 5 cities or 3.5 percent Note: Null hypothesis is that each relative price series contains a unit root. 21 Conclusion Converging to the national mean price Converging to the national mean price Converging to the national mean price Converging to the national mean price Converging to the national mean price *** and ** denote 1% and 5% significance level, respectively. Table 2: Panel Unit Root Tests of Relative Price Series for China's 105 Cities Panel A: Wine Method Null: Unit root (assumes common unit root process) Levin, Lin & Chu t Statistic Prob.** 4.167 Null: Unit root (assumes individual unit root process) Im, Pesaran and Shin W-stat ADF - Fisher Chi-square 1 2.183 207.89 0.986 0.4891 Panel B: Beer Method Statistic Null: Unit root (assumes common unit root process) Levin, Lin & Chu t* Null: Unit root (assumes individual unit root process) Im, Pesaran and Shin W-stat ADF - Fisher Chi-square 1.003 Prob.** 0.842 4.256 1 215.66 0.918 22 Discussion and Conclusions The main objective of study is to investigate the level of integration of the retail market on beer and wine across regions in the largest transitional market of China. We can conclude that Chinese alcoholic markets are not well integrated, and there is no evidence of significant arbitrage activities in the wine and beer markets. After more than a decade’s integration with the world’s economy following its economic reforms and accession to World Trade Organization (WTO), China remains as a collection of separate regional markets protected by barriers rather than a single market, as reported by Poncet (2005). There has been limited cross-regional price convergence that can be reflected in the test of the Law of One Price in beer and wine markets. Our evidence of beer and wine prices across different cities in the country tends to support Young (2000) and Poncet’s (2005) observation, that China remains a fragmented market, opposing Holz’s (2009) argument that China has become a relatively integrated economy. There are several factors that could affect market integration as discussed in the literature review section. Speedy access to quality price information and the availability of transport facilities are the most cited exogenous factors affecting price behaviour (Zhou et al., 2000). Given the fast and widely adoption of the internet, mobile technology and other Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), and the drastic improvement of transportation facilities particularly the development of high speed railways in China, the information and transport factors might no longer pose barriers to interregional trade. One of the major factors of interregional trade barriers could be local governments’ protectionism. As argued by Young (2000), although the central government has released control over prices, this function has been taken up by local governments. Poncet (2005) points to local protectionism as a major barrier to market integration, because local governments pursue a dual objective of socioeconomic stability preservation and fiscal revenues maximization. Due 23 to the growing interregional competition between duplicative industries, such as beer and wine production, local governments imposed a variety of interregional barriers to trade, which subsequently led to the fragmentation of the domestic market. Other key factors that inhibit market integration are the historic differences among regions within China. One of such factors is the interregional income disparity in China, which is particularly prominent. Pedroni and Yao’s (2006) study shows that per capita incomes in the coastal provinces do not appear to be converging toward one another. The authors reveal that the growth patterns among provinces with similar degrees of preferential open-door policies follow divergent paths, and likewise the growth of interior provinces as a group do not show a converging pattern, but are in general diverging too. Lau (2010) further reports that the gap of income levels between Chinese provinces have been widening since the country’s economic reforms. The growth patterns along with other differential factors among regions in China are unlikely to become homogenous in the short run. Yet all these factors will continue to influence the economic performance of these regions as well as their differential consumer demand and subsequently prices. The benefits of regional integration, the aggregate efficiencies associated with internal integration are usually desirable (Baldwin and Venables, 1995). Moreover, internal integration may also have important redistributive effects, because the reductions in the costs of inter-regional transactions help to reduce interregional income differences and increase national growth rates (Martin, 1999). However, as suggested by Eberhardt, Wang, and Yu (2013), local protectionism prevents the efficient allocation of resources and attenuating the benefits of scale economies and spatial spill-overs and such protective behaviour not merely harms domestic market efficiency, but also offsets potential gains from a more liberal international trade policy regime. Implications for policy development of this study are that the Chinese central government needs to reduce local governments’ protectionism in the beer 24 and wine markets so as to promote market integration and thus market efficiency. Moreover, government policies should also encourage brewers in the country to specialize according to their comparative advantages. Obviously local traders who want to take advantage of price differential among different cities will not be successful because of the lack of arbitrage opportunities and the unique market structure in these markets (i.e. allocative inefficiency). Further reforms to reduce regional disparity are imperative. The Chinese government has already implemented policy initiatives such as the “Western Great Development” in 1998, the “Northeast Revival” in 2003 and the “Rise of Central China” in 2004 to narrow the gaps of economic development between regions in China. These policies provide excellent opportunities for investors, both foreign and domestic. The relatively poor regions have comparative advantages such as the low prices of land and labour prices. As our study shows that regional disparity still exists, it is recommended that the government should focus on public investment in infrastructure and education systems, improving the efficiency of production and increasing the rate of returns on investment in the lagging regions. Continued financial reform is particularly needed in order to improve investors’ access to finance in inland provinces and rural areas (Wang, Wan and Yang, 2014). Furthermore, as Wang et al. (2014) suggested, both central and local governments should assume a clear and proper role, for example, the central government should focus on regional equalisation while the local governments should focus on public services and social development. Implications for foreign brewers entering Chinese market are that they must not consider China as one single market but as multiple subnational regional markets, as there is lack of market integration within China as shown in this study. Given that China is such a segmented market and the increasing purchasing power of a growing middle class in China’s major cities, one strategy for foreign beer brands is to focus on highly developed cities such as Beijing and Shanghai. There is plenty of opportunity for foreign beer and wine brands to 25 succeed in China, as per capita beer consumption is only 35 litres annually when comparing to 75 litres in the U.S. This is particularly true for premium beer because consumers’ willingness to pay is higher for foreign brands that give them superior status perception. The main limitation of our study is that we do not examine the determinants of price divergence and future research has to address this issue in more detailed ways. Another future research direction could be consumption convergence for beer and wine. There is a significant regional disparity in income and wealth across Chinese regions (Lau, 2010). Therefore it is interesting to examine whether big cities generate higher demand (consumption per person) compared to small towns out in the provinces. 26 References Access Asia Limited, 2010. Beer in China 2010: a market analysis. Shanghai, China. Baldwin, R. E. and Venables, A. J. 1995. Regional economic integration, in G. Grossman and K. Rogoff (Eds.), Handbook of International Economics, Vol. III, Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, 1598-1644. Bledsoe, J. 2011. Economic Reform and Market Growth in China - Effects of China’s Economic Reforms on the Domestic Beer Market and its Consumers. University of Washington. Bouzdine-Chameeva, T., Zhang, W. & Pesme, J-O. 2013. Chinese wine industry: current and future market trends. AAWE Conference, Stellenbosch, June 2013. Campbell, J. Y., & Perron, P. 1991. Pitfalls and opportunities: what macroeconomists should know about unit roots. In NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1991, Volume 6 (pp. 141-220). MIT press. Chen, Q., Goh, C.-C., Sun, B., & Xu, L. C. 2011. Market integration in China. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series, WPS 5630. Chow, J. 2014. China is now world’s biggest consumer of red wine. The Wall Street Journal. 29 January 2014. Retrieved on 18 April 2015. http://blogs.wsj.com/scene/2014/01/29/china-is-now-worlds-biggest-consumer-of-redwine/ CSIS. (2015). China Economic reform timeline. 05 August 2015. Retrieved on 06 August 2015. http://csis.org/blog/china-economic-reform-timeline Cui, C.L., Xu, M.F. & Kao, J. 2012. China’s beer industry: breaking the growth bottleneck. Research Report. Accenture Institute for High Performance, Accenture. Dickey, D. A., & Fuller, W. A. (1979). Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Journal of the American statistical association, 74(366a), 427-431. Dolado, J. J., Jenkinson, T., & Sosvilla-Rivero, S. 1990. Cointegration and unit roots. Journal of Economic Surveys, 4(3): 249-273. Eberhardt, M., Wang, Z., & Yu, Z. 2013. Intra-national protectionism in China: Evidence from the public disclosure of ‘illegal’ drug advertising, (WPS/2013-07). Retrieved on 21 June, 2015. https://www.sherpa.ac.uk/gep/documents/papers/2013/2013-04.pdf Fan, C. S., & Wei, X. 2006. The law of one price: evidence from the transitional economy of China. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(4): 682-697. 27 Fan, S., Wailes, E. J., & Cramer, G. L. (1995). Household demand in rural China: a two-stage LES-AIDS model. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 77(1), 54-62. Gibson, A. J. 1995. Prices, food and wages in Scotland, 1550-1780. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Gil-Pareja, S., & Sosvilla-Rivero, S. 2008. Price convergence in the European car market. Applied Economics, 40(2): 241-250. Gravier-Rymaszewska, J., Tyrowicz, J., & Kochanowicz, J. 2010. Intra-provincial inequalities and economic growth in China. Economic Systems, 34(3): 237-258. Heracleous, L. 2001. When local beat global: the Chinese beer industry. Business Strategy Review, 12(3): 37-45. Holz, C. A. 2009. No razor's edge: Reexamining Alwyn Young's evidence for increasing interprovincial trade barriers in China. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 91(3): 599-616. Huang, J. & Bouis, H. 1996. Structural changes in the demand for food in Asia. Food, Agriculture, and the Environment Discussion Paper 11. Washington: International Food Policy Research Institute. Huang, J. & Rozelle, S. 1998. Market development and food demand in rural China. China Economic Review, 9: 25–45. Huang, J., Rozelle, S., & Chang, M. 2004. Tracking distortions in agriculture: China and its accession to the World Trade Organization. The World Bank Economic Review, 18(1): 59-84. Im, K. S., Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (2003). Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. Journal of econometrics, 115(1), 53-74. Jenster, P. & Cheng, Y. 2008. Dragon wine: developments in the Chinese wine industry. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 20(3): 244-259. Lau, C.K.M. (2010), New evidence about regional income divergence in China, China Economic Review, 21(2): 293–309. Lau, M. and Akhmedjonov, A. 2012. Trade barriers and market integration in textile sector: evidence from post-reform Russia. Journal of the Textile Institute, 103 (5): 532-540. Li, Z. 2011. Chinese Wine, Cambridge University Press. Levin, A., Lin, C. F., & Chu, C. S. J. (2002). Unit root tests in panel data: asymptotic and finite-sample properties. Journal of econometrics, 108(1), 1-24. Liu, F. & Murphy, J. 2007. A qualitative study of Chinese wine consumption and purchasing: Implications for Australian wines. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 28 19(2): 98-113. Lodge, A. 2012. US tops global wine consumption chart, The Drinks Business. 11 January 2012. Retrieved on 18 April 2015. http://www.thedrinksbusiness.com/2012/01/us-tops-global-wine-consumption-chart/ Lutz, M. 2004. Pricing in segmented markets, arbitrage barriers and the Law of One Price: Evidence from the European car market, Review of International Economics, 12(3): 456– 75. Maddala, G. S., & Wu, S. (1999). A comparative study of unit root tests with panel data and a new simple test. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and statistics, 61(S1), 631-652. Martin, P. 1999. Public policies, regional inequalities and growth, Journal of Public Economics, 73: 85-105. Nagayasu, J., & Liu, Y. 2008. Relative prices and wages in China: evidence from a panel of provincial data. Journal of Economic Integration, 23(1): 183-203. Pedroni, P., & Yao, J. Y. (2006). Regional income divergence in China. Journal of Asian Economics, 17(2): 294-315. Perkins, D. H. (1988). Reforming China's economic system. Journal of economic literature, XXVI, 601-645. Perman, R. 1991. Cointegration: an introduction to the literature. Journal of Economic Studies, 19: 3-30. Poncet, S. 2005. A fragmented China: measure and determinants of Chinese domestic market disintegration. Review of international Economics, 13(3): 409-430. Ravallion, M. 1986. Testing market integration. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 68(1): 102-109. Stone, G. 2014. China leaps into top spot for red wine. The Drinks Business. 28 January 2014. Retrieved on 18 April 2015. http://www.thedrinksbusiness.com/2014/01/china-leaps-into-top-spot-for-red-wine/ Su, C. (2011). Internationalization and Glocal Linkage: A study of China's Glocalization (1978 -2008). In Y. Wang (Ed.), Transformation of Foreign Affairs and International Relations in China, 1978-2008 (333-366). The Netherlands: Brill. Swinnen, J.F.M. 2011. The economics of beer. In Junfei Bai, Jikun Huang, Scott Rozelle &Matt Boswell. Beer Battles in China: The Struggle over the World’s Largest Beer Market. Oxford Scholarship Online. Verboven, F. 1996. International price discrimination in the European car market, Rand Journal of Economics, 27(2): 240–68. 29 Wang, C., Wan, G., & Yang, D. (2014). Income inequality in the People's Republic Of China: trends, determinants, and proposed remedies. Journal of Economic Surveys, 28(4): 686708. Young, A. 2000. The razor's edge: Distortions and incremental reform in the People's Republic of China. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(4): 1091 -1135. Yu, L., Lu, J., & Luo, P. 2013. The Evolution of Price Dispersion in China's Passenger Car Markets. The World Economy, 36(7): 947-965. Zhao, Y. 2003. The role of migrant networks in labor migration: The case of China. Contemporary Economic Policy, 21(4): 500–511. Zhou, Z. Y., Wan, G. H., & Chen, L. B. 2000. Integration of rice markets: the case of southern China. Contemporary Economic Policy, 18(1): 95-106. 30 Appendix : Chinese cities included in our study Anqing Anshan Anshun Baoji Baotou Bayingolin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture Beihai Beijing Bijie Changchun Changde Changsha Changzhi Chengdu Chenzhou Chongqing Chuzhou Dalian Daqing Datong Fuzhou Ganzhou Golmud Guandu District Guangzhou Guigang Guilin Guiyang Haikou Hami Prefecture Hangzhou Hanzhong Harbin Hefei Hengshui Heze Hinggan League Hohhot Huangshi Hulunbuir Huzhou Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture Jiamusi Jiangmen Jiaxing Jilin Jinan Jincheng Jinhua Jinzhou 31 Jiujiang Jiuquan Kongtong District Kunming Lanzhou Lhasa Lishui Liupanshui Liuzhou Mudanjiang Nanchang Nanjing Nanning Nanping Nantong Nanyang Neijiang Ningbo Ordos City Panjin Panzhihua Pengxi County Pingluo County Pu'er City Puyang Qiandongnan Prefecture Qianjiang Qiannan Prefecture Qianxinan Prefecture Qingdao Qinhuangdao Quanzhou Qujing Quzhou Renshou County Sanming Sanya Shanghai Shangqiu Shantou Shaoguan Shaoxing Shenyang Shenzhen Shijiazhuang Shizuishan Suzhou Tai'an Taiyuan Taizhou Tangshan Tianjin Tianmen Tieling Tonghua Tongling Tongren Ürümqi Weinan Wenzhou Wuhai Wuhan Wuhu Wuzhong Xi'an Xiamen Xiangyang Xianyang Xingtai Xining Xinxiang Xuanhan County Xuzhou Yan'an Yanbian Prefecture Yangzhou Yantai Yichang Yichun Yinchuan Yiyang Yuncheng Zaozhuang Zhangshu Zhangzhou Zhanjiang Zhengzhou Zhongwei Xian Zhoukou Zhoushan Zhuhai Zunyi 32 33