Effects of Television Commercial Repetition, Receiver Knowledge, and Commercial Length:... Test of the Two-Factor Model

advertisement

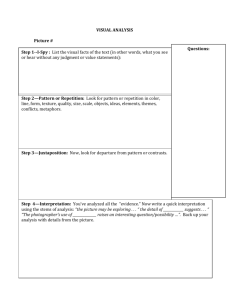

Effects of Television Commercial Repetition, Receiver Knowledge, and Commercial Length: A Test of the Two-Factor Model Author(s): Arno J. Rethans, John L. Swasy, Lawrence J. Marks Reviewed work(s): Source: Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 23, No. 1 (Feb., 1986), pp. 50-61 Published by: American Marketing Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3151776 . Accessed: 31/01/2012 23:11 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. American Marketing Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Marketing Research. http://www.jstor.org ARNO J. RETHANS,JOHN L. SWASY, and LAWRENCEJ. MARKS* Theauthorsreviewthe two-factorelaborationmodelof messagerepetitioneffects and report a study of the model'sapplicabilityto new productadvertising.The studyfindingsdo not supportthe hypothesizedinverted-Urelationshipbetweenrepetitionand attitudetowarda novel commercialand product. However,the underlyingprocessesof learning,tediumarousal,and elaborationwere observed.Viewer knowledgeand commerciallengthdid not moderatethese processes. Effects Television of Knowledge, and Receiver A I Test Commercial of the Two-Factor Repetition, Commercial Model I I Length: ? The theoretical explanations offered for the observed repetition effects have been borrowed from the social psychology literature rather than originating within advertising and marketingcommunication research. In particular, Berlyne's (1970) two-factor theory and the twofactor cognitive response model by Cacioppo and Petty (1979, 1980) have been thought to hold promise for explaining past empirical results in marketing. Much more research, however, is warrantedto test the appropriateness and practical utility of these theoretical accounts (Cacioppo and Petty 1980; Sawyer 1981). Specifically, additional research is needed to determine whether the two-factor model and the processes (learning and tedium) presumed to underlie attitude formation are appropriate for describing audiences' response to repeated advertisement exposures. We report a study designed to test the two-factor model within a new product advertising context. To provide a more thorough test of the model, the ad-processing-related variables commercial length and receiver knowledge were incorporatedin the experimental design. The effects of repeated exposure to an advertising message have long been of considerable basic and pragmatic interest to marketers. Early research on the effects of repetition was motivated by the need to estimate the parametersof a repetitionfunction to be incorporatedinto advertising media models (Aaker 1975; Little and Lodish 1969; Ray and Sawyer 1971a, b; Ray, Sawyer, and Strong 1971). Subsequent research examined the effects of advertising repetition on more general outcome measures such as attitudes, recall, and behavioral intention (Ginter 1974; Gorn and Goldberg 1980; Mitchell and Olson 1977; Winter 1973). More recently, research efforts have shifted toward a consideration of the underlying processes that create the various observed responses to an advertising message after multiple exposures. Researchers adopting the latter avenue of inquiry are attempting to show how the effects of repetition might be explained by message-receiver-generated cognitive responses (Belch 1982; Calder and Sternthal 1980; Sawyer 1981; Wright 1980). THEORETICALBACKGROUND In 1968, Zajonc developed the empirical generalization that mere exposure is sufficient to produce increased positive attitude toward a novel object. This exposure effect has been replicated under many conditions. Other studies, however, have found moderation effects (i.e., an inverted-U-shaped curve) or novelty effects (i.e., a decrease in affect with repeated exposure). Several theories-response competition, optimal arousal, and two- *Arno J. Rethans and John L. Swasy are Assistant Professors of Marketing, The Pennsylvania State University. Lawrence J. Marks is Assistant Professor of Marketing, University of Southern California. The authors thank Daniel W. Matthaidess, Coordinator of Communications Research, The Eastman Kodak Company, for providing the stimulus commercials, Gregory Boiler, Mary Dwonzyck, and Manoj Hastak for their assistance in data collection and analysis, and the JMR reviewers for their constructive comments. The research was funded by a research grant to the first two authors from the Center for Research, The Pennsylvania State University. 50 Journal of Marketing Research Vol. XXIII (February 1986), 50-61 WITHIN TWO-FACTOR THEORY ADVERTISING Figure1 TWO-FACTOR THEORY OF AFFECT TOWARDA REPEATED STIMULUS Affect Postive Learing Factor , /'^~ Z z 5 s $5 "^ Numberof Exposures Net Effect \ \^.Negative TediumFactor factor-have been proposed to explain these effects. Of these, the two-factor theory seems to have a degree of face validity and has been considered a potentially worthwhile approach within more natural communication-processingenvironments(Belch 1982; Sawyer 1981). The two-factor theory suggests that two opposing factors determine attitude toward a repeatedly viewed stimulus (Figure 1). First, during initial exposures an increasingnet positive affect is observed which is postulated to be due to (1) a reduction in uncertainty and conflict toward the initially novel stimulus (Berlyne 1970) or (2) an increasing opportunity to learn more about the stimulus (Stang 1975). Next, at higher levels of exposure a negative response begins to dominate which leads to a decrease in affect toward the stimulus. This negative response is posited to be due to boredom, decreased incremental learning, satiation, reactance, and/or tedium (Sawyer 1981). The net effect of these two opposing factors is an inverted-U relationship between number of exposures and attitude. More recently, Cacioppo and Petty (1979, 1980) postulated that the attitudinal effects of message repetition are mediated by the elaborations (i.e., counter and support arguments) that viewers generate when exposed to advertisements. Taking a two-factor perspective, Cacioppo and Petty (1980) propose that repeated exposure through moderate levels of repetition acts primarily to provide additional opportunity for attending to, thinking about, and elaboratingupon the message arguments. This additional processing opportunity enables the message recipient to realize the message arguments' cogency and favorable implications which, in turn, enhances persuasion. At high levels of message repetition, however, re- 51 actance and/or tedium begin to dominate processing and focus recipients' cognitive energies on counterarguing, thereby decreasing persuasion. In combination, these opposite processes bring about the inverted-U relationship between repetition and message acceptance. Advertising research has identified additional variables that may further influence receivers' opportunity and/or ability to elaborate. In particular, the variables receiver knowledge and commercial length are seen as being manageriallyimportantfactors and have been noted for restrictingor enhancing the extent and nature of cognitive elaboration (Bogart and Lehman 1983; Edell and Mitchell 1978; Gardner 1983; Olson, Toy, and Dover 1982; Webb 1979; Wells, Leavitt, and McConville 1971; Wheatley 1968). For example, Edell and Mitchell (1978) suggest that receivers' elaboration is based in part on relevant knowledge structures. The specific content of these structures is presumed to determine the number, type, and content of cognitive responses to advertisements. Hence, when considering repetition effects, one might reasonably expect differences in receiver knowledge to affect viewers' rates of learning, tedium arousal, and attitude formation. Similarly, message length has been shown to affect receivers' processing of a persuasive message (Calder, Insko, and Yandell 1974). In an advertisingcontext Wells, Leavitt, and McConville (1971) and Wheatley (1968) found that the longer commercial resulted in different viewer responses. In the Wells et al. study the longer commercial, though similar in format and theme to the shorter version, presented more product usage vignettes which increased the opportunity for the respondents to elaborate on the message. The larger number of vignettes was thought to have caused respondents to engage in more counterargumentationwhich led to a more negative attitudetoward the advertisement.Wheatley also reported that commercial length affected viewers' attitude toward the ad. Though these studies did not specifically assess the extent and nature of cognitive responding, the results suggest that commercial length may influence receivers' elaboration and thus possibly moderate repetition effects. The two elaboration-relatedvariables, receiver knowledge and commercial length, help define a richer framework in which to test the appropriateness of the twofactor theory. In general, one might propose that the curvilinear repetition-attituderelationship is most likely to be observed when message arguments and product features are illustrated in a larger number of usage settings (i.e., under conditions of a longer commercial) and when viewers are highly knowledgeable and capable of faster initial processing of the information contained in the advertisement. Beyond this general proposition, several specific and interrelatedresearch issues pertaining to the appropriatenessof two-factor theory can be identified. 1. The effects of process-relatedvariableson the extentof learning. 2. Measurementof reactance/tedium. FEBRUARY 1986 OF MARKETING JOURNAL RESEARCH, 52 affect criteriawithinthe ad3. Specificationof appropriate vertisingcontext. 4. Developmentof an advertising-context-relevant cognitive responsetypology to describeviewers' elaboration duringrepeatedexposures. 5. Determinationof the relationshipbetween elaboration activityand the variousaffect criteria. Learning Two-factor theory suggests that repetition of a stimulus provides an opportunity for learning. Indeed, numerous studies have shown that repetition leads to better recall of message content (Belch 1982; Cacioppo and Petty 1979; Sawyer 1981; Sawyer and Ward 1979). On the basis of these studies and our preceding discussion of commercial length and receiver knowledge, we hypothesize that H1: Familiaritywith andrecallof a novel televisioncommercial will increase as exposure frequency increases,particularlyfor high knowledgeindividuals exposed to the longer version of the experimental commercial. Tedium The two-factor model further postulates that at higher levels of repetition, reactance or tedium influences attitude towardthe stimulus negatively. Cacioppo and Petty (1979) hypothesize that at higher levels of re-exposure, tedium or reactance motivates a recipient to attack the now-offensive message and thus results in renewed argumentation and decreasing agreement with the message. Despite its major role in the explanation of repetition effects, tedium has not been assessed explicitly in any of the past empirical studies. Rather, evidence has been collected and found to be either consistent or inconsistent with the tedium hypothesis. Until the effect of repetition on receiver tedium is assessed directly, one cannot verify the development of tedium in response to television commercial repetition nor its effect on responses to the commercial. In their discussion of tedium, researchersseem to have conceptualized this factor as an increasingly negative feeling and reaction toward experiencing the stimulus again. This conceptualization is the basis for the measures of tedium used in our study, and we hypothesize that H2: Tediumincreasesas the frequencyof exposureincreases,particularlyfor high knowledgeindividuals exposedto the longercommercial. Attitude Criteria In the early mere-exposure experiments affect toward the stimulus was the criterion of interest and was operationalized by having subjects guess the goodness/badness of Turkish or Chinese characters (Zajonc 1968). Similarly, Stang (1975) had subjects rate Turkish words for pleasantness. In the Cacioppo and Petty series of ex- periments (1979, 1980), affect was operationalized by having subjects rate their level of agreement with an advocacy message. Single measures of this type may not be sufficient to capture the complexity of consumer response to a television commercial. As a result, the conceptualizationand operationalizationof appropriateaffect criteria within an advertising context pose some additional challenges. In a review of research on advertising's affective qualities, Silk and Vavra (1974, p. 168) were prompted to note that the concept of affect had not been defined clearly in either theoretical or operational terms. Consequently, we find a variety of affect-related measures in advertising and marketing communication studies including attitude toward the product/brand, attitude toward purchasing and/or using the product, and attitude toward the company, as well as attitude toward the advertisement. Only recently have researchers attempted to unravel the relationships among these constructs (Mitchell and Olson 1981; Shimp 1981). What is important for purposes of the current research is whether or not exposure frequency affects these constructs in the same manner. To explore this question, we hypothesize that H3: Withinan advertisingcontextthe favorabilityof severalaffect-relatedmeasures(i.e., attitudetowardthe commercial,attitudetowardthe product,purchase intention, and attitude toward the company) increaseswith moderatelevels of exposure,then declines afterhigh levels of exposure,particularlyfor high knowledge individualsexposed to the longer versionof the experimentalcommercial. Cognitive Elaborations and Repetition The cognitive response version of the two-factor model suggests that the relationship between repetition and attitudes may be explained by the cognitive responses message recipients are able and motivated to produce. Cacioppo and Petty (1979, 1980) introduce the distinction between "content-relevant" and "content-irrelevant" cognitive elaborations to explain the inverted-U relationship between repetition and attitude. In their experimentselaborationswere designated as content or topic "relevant"if they had a non-neutral valence with respect to message's point of view. Through a complex partialing procedureCacioppo and Petty show that content-relevant elaborations were responsible for the attitudinaleffects due to repetition. In the advertising reception environment, it may be helpful to determine more specifically what constitutes relevant and irrelevant elaborations, that is, a classification of cognitive elaborations which highlights the specific content of the elaborative processing. A review of literature(Belch 1982; Lutz and MacKenzie 1982; Wright 1973) and a perusal of cognitive responses obtained from other commercial testing suggest the content topics of ad- and product-relatedresponses. To explore the appropriateness of the "topic relevancy" explanation we hypothesize that H4: Thefrequencyof positive(negative)"topic-relevant" WITHINADVERTISING THEORY TWO-FACTOR thoughtswill increase(decrease)with moderatelevels of exposureanddecrease(increase)withhighlevels of exposure, particularlyfor high knowledge individuals exposed to the longer version of the commercial. Mediating Role of Cognitive Elaborations The content-basedcodingschemeallows for the study of whether excessive exposure generates repetitionrelated elaborationsrather than influencing the more traditional,valence-based, counterargumentationand favorable message-related cognitive responses (i.e., "relevant" thoughtsas suggestedby CacioppoandPetty). As a result, the mediatingrole of repetition-related responsescan be assessed more precisely. Thecontent-basedcodingschemealso providesan improvedbasis for addressingthe mediatingeffect of product- andad-relatedelaborationson brandattitude.Product-related elaboration and brand attitude may be consideredthe advertising contextequivalentsof the topicrelevantelaborationand attitudedesignationsused by Cacioppo and Petty. Ad-relatedelaborationsmay be considered"irrelevant." The recentworkby Mitchelland Olson (1981) relates to this issue. They examinedthe relativecontributionsof attitudetowardthe ad (Aad), attitude towardthe pictureused in the ad (Api), and a Fishbeincognitive structureindex in predictingattitude towardthe product(Ao) and attitudetowardbuying the product(Aact).They observedthatattitudetowardthe ad made a significantcontributionto the predictionof Ao andAactbeyondthatprovidedby the cognitivestructure index. They furtherobservedthat Aadhad its majorinfluenceon Ao andAactbut not on purchaseintent,which was determinedprimarilyby Aact.These observationsled themto concludethat productattributebeliefs may not be the only mediatorsof the variationin brandattitude producedby advertisements.For purposesof our study, the MitchellandOlsoneffortsuggeststhatbothproductand ad-relatedelaborationsare "relevant"and mediate attitudetowardthe new product.Fromthese resultswe hypothesizethat elaborationsas well H5:Indicesof the net product-related as indices of net ad-relatedand repetition-related elaborationsare significantpredictorsof receiverattitudetowardthe productand purchaseintention. In summary,on the basis of a review of the literature in the areas of social psychology, marketing,and advertising,we advancea series of five hypotheseswhich in combinationexaminethe appropriateness of the twofactortheorywithinan advertisingcontext.The firstfour hypothesesproposethree-wayinteractioneffects due to repetition,knowledge,andcommerciallength. It should be notedthatminimumsupportfor the two-factortheory is to be foundin the presenceof repetitionmaineffects. The moredemanding,albeitexploratory,tests proposed involvethe assessmentof two- and three-wayrepetition interactioneffects. If presentand in meaningfuldirec- 53 tions, these interactionswould demonstratemore thorof the theoryin an advertisoughlythe appropriateness ing context. METHOD Overview A 2 x 2 x 3 between-subjectsdesign was used with receiverknowledge(high or low), commercialversion (30 or 90 seconds), and repetition(one, three, or five exposures)as the factors. Launchcommercialsfor the KodakDisc camerawere made availablepriorto their nationalairingand served as test stimulifor the study. Afterexposure,measurementswere takenon cognitive responses,attitudes,and recall. Procedure studentswere invitedto participatein Undergraduate a study ostensibly designed to investigatemass comandproductusage.Four munication,sportsprogramming, hundredand fifty screeningquestionnaireswere administeredto definea subjectpool consistingof subjectswith two differentlevels of knowledgeaboutand experience with photographicequipment.Questionsabout camera equipmentownership and perceived knowledge were embeddedin the screeningquestionnaireand served as subjectselectioncriteria.High knowledgesubjectswere definedas those who ownedandused at leastone 35mm formatcameraandratedtheirknowledgeaboutcameras as beingvery high or at an expertlevel. Low knowledge subjectswere those who had no or only infrequentexperiencewith Instamatictype camerasand who rated themselvesas not at all knowledgeableabout cameras (cf. Bettmanand Park 1980). The applicationof these criteriaresultedin the identificationof 130 eligible participants. Significant differences between the low and high knowledgegroupswerefoundin productownershippatterns and the numberof rolls of black and white film (0.03 vs. 4.35), color prints(2.17 vs. 6.11), and slides (0.05 vs. 1.42) used in the last six months.The average dollarinvestmentin photographic equipmentwas $48 for the low groupand $395 for the high group. Thus, dramaticdifferencesin experiencewith photographywere observedbetweenthe high and low knowledgegroups. Subjectsof the two knowledgeconditionswere assigned randomlyto one of the six experimentaltreatments (two versions of the commercialby three levels of repetition).Upon arrivalat the researchsettingsmall groupsof subjectswere read a set of instructionsfrom a preparedscript which presentedthe study guise and the requiredtasks. After listening to the instructions, subjectswereshowna 40-minutetelevisionprogram,"The Gamesof the XXIst Olympiad,"that includedthe experimentaland other commercialsduring the regular commercialbreaks.The test commercialswere assigned to commercialbreaksin such a way that spacedrepetition ratherthansuccessiveor massedrepetitionwas accomplished. 54 Repetitionwas operationalizedat threelevels of commercialexposure(cf. Belch 1982; Cacioppoand Petty 1979, 1980;GornandGoldberg1980). Two groupswere exposedto one launchcommercialinsertedat the end of the program.Two additionalgroups viewed three exposuresinsertedat the beginning,middle,andend of the program.Two other groupsviewed five exposuresinsertedin the naturalcommercialbreaksat aboutequal intervalsthroughoutthe program.Thus, in each group the last commercialshown was the stimulusad. Immediatelyafterthe programsubjectswere askedto evaluatethe program,completea cognitiveresponsetask, and respondto dependentmeasuresaboutattitudesand recall. Stimulus Ads To increasethe mundanereality of the experiment, actualnew productintroductionads were used as stimuli. Subjects were exposed to a never-before-shown, professionallyproducedtelevision commercialthat introduceda trulynew product.As a resultsubjectswere providedan opportunityto learn about a new product and a new commercial,and hence the effects of repetitionon attitudeformationcould be assessed. Two versionsof the commercialwere used. A 30-second anda 90-secondversionof the commercialfeatured similaraudiocontentandorganizationbutdifferedin the numberof usage situationvignettesdesignedto dramatize the many uses and benefits of what Kodaktermed its new "decision-free"photography.The differencein length thereforewas due primarilyto the numberof productusageillustrationshighlightingtheproduct'sdistinctive features. More importantfor purposesof our study, however, was the fact that the two versions affordeddifferentialopportunityto elaborateon the message. Variables and Operationalizations The extent to which the test commercialcreated a memorableimpressionin relationto the competingcommercialswas assessed. Immediatelyafterthe program, respondentswere askedto indicatewhich one commercial "stoodout most in your mind."After elicitationof cognitiveresponses,recall of the advertisementcontent was measuredby asking subjectsaboutthe sales points presentedin the ad and identifiedby EastmanKodakas beingthe communicationobjectivesfor bothversionsof the commercial.Specifically,subjectswere askedto instatementsweremade dicatewhichof 12 productattribute in the commercial. explicitly Only five of the 12 statementsactuallywere madein the commercial.The numberof correctsalespointsidentifiedwas usedas the aided recallmeasurefor the study. To assess tedium, subjectswere asked to rate their feelingstoward"watchingthe KodakDisc cameracommercialagain"on a series of threesemanticdifferential scales havingthe same bipolaradjectivesas were used in the otherattitudemeasures(alpha = 0.97). In addi- JOURNAL OF MARKETING FEBRUARY 1986 RESEARCH, tion, a measureof the valence of repetition-related cognitiveresponseswas viewed as a furtherindicantof tedium (Belch 1982). Attitudestowardthe ad, product,and companywere operationalizedas the mean on three 7-point semantic differentialscales (very bad/very good; dislike/like; negative/positive).Coefficientalpha for each measure was 0.94 or better.Purchaseintentionfor the new camera was measuredas the mean score of two semantic differentialscales (disagree/agree;true/false)following the statement,"I will buy the new KodakDisc camera withinthe next 12 months"(alpha = 0.91). Also measured on 7-point semanticdifferentialscales was perceivedfamiliarity(i.e., not at all familiar/veryfamiliar) with the commercialand the cameraitself. Cognitive Responses and Their Classification Subjectswere askedto list whateverthoughts,ideas, or reactionsthey experiencedwhile watchingthe camera commercial.The set of categoriesused to classify these favorablethoughts, responsesincludedcounterarguments, and neutralthoughts(Cacioppoand Petty 1979, 1980) as well as the topic categoriesof product-related,adandother.Within related,repetition-related, study-related, eachof the majorcategoriesthe thoughtswere classified furtheras being positive or negative, supportedor unsupported,or whetherthey constituteda curiositystatement. A three-judgepanelclassifiedall cognitiveresponses. Thejudges agreedon 84%of the judgements.The final determination for the remaining16%was based on the modalratingby the threejudges aftera discussionhad takenplace. RESULTS Learning Subjects'perceivedfamiliaritywith the stimuluscommercialandnew productbothwere affectedby exposure frequency (F(2,118) = 24.56, p < 0.01; F(2,118) = 4.56, p < 0.05, respectively).Also affectedby repetitionwas recognitionof the messagearguments.The aided recallof sales pointsmeasureincreasedas levels of repetition increased (M(1) = 2.73, M(3) = 3.19, M(5) = 3.61, F(2,118) = 5.62, p < 0.01). Finally, as exposure frequencyincreased,the perceiveddistinctivenessof the test commercialin relationto the surroundingads increased (M(1) = .44, M(3) = .80, M(5) = .86; F(2,118) = 12.38, p < 0.01). These findingsreplicateprevious studies'resultsand supportthe hypothesizedrepetition effecton receiverlearning.However,this effect was not moderatedby either commercial length or receiver knowledge. Tedium Tediumwas defined as the subject's feeling toward viewingthe test commercialagain. An analysisof variance reveals that the tedium scores differ significantly WITHIN ADVERTISING THEORY TWO-FACTOR 55 Table 1 MEANSCORESON ATTITUDE MEASURES One exposure 30-second commercial Attitude toward product Intentionto purchase Attitudetowardad Attitudetowardcompany Three exposures Five exposures Low know High know Low know High know Low know High know 5.27a 1.75b 5.05 5.37 5.67 5.69 5.53 1.50 5.00 6.41 2.40 5.07 5.20 1.85 5.60 6.67 2.73 5.18 5.97 2.35 5.57 6.53 5.84 2.23 4.94 5.91 6.30 2.65 5.73 5.83 5.18 3.27 5.30 6.00 5.72 1.73 5.17 5.97 5.10 2.25 5.10 5.80 4.03 6.03 90-second commercial Attitudetowardproduct 5.48 Intentionto purchase 2.64 Attitudetowardad 5.61 Attitudetowardcompany 5.82 'Attitudescale values: 1-unfavorable,7-favorable. bPurchase intentvalues: 1-disagree,7-agree. across levels of repetition. A repetition main effect (F(2,118) = 5.21;p < 0.01) is observed, indicating that subjects in the one-exposure condition had a more positive attitude toward seeing the commercial again than did subjects in the three- and five-exposure conditions. The mean attitudinal scores for the three conditions are 2.88, 3.78, and 4.10 respectively (1 = very good and 7 = very bad). The second indicant of tedium, the net valence index of repetition-relatedresponses, also exhibits a significant main effect due to repetition (F(2,118) = 13.22; p < 0.01). This effect is due to differences in the numberof negative repetition-relatedresponses which show a repetition main effect (F(2,118) = 13.17; p < 0.01). The mean number of negative repetition-related responses increases dramatically from one to three exposures (0.00-0.95) and increases negligibly from the three to five exposures (0.95 to 0.96). No higher order interactions with knowledge and commercial length are significant. Hence, the hypothesized repetition effect on tedium is supported. Attitude Criteria The third hypothesis pertains to the effects of repetition on several measures of attitude and purchase intention.1 The mean scores on these measures categorized by recipient knowledge and commercial length for the one-, three-, and five-exposure conditions are reported in Table 1. Viewers across all conditions expressed a generally favorable evaluation of the new product and indicated a low probability of buying the product within the next 12 months. As can be observed in Table 2, viewers' attitudes toward the product, ad, and company and their purchase 'The intercorrelations among attitudetowardthe product(X,), attitudetowardthe ad (X2),attitudetowardthe company(X3),andpur- chase intention (X4)are r,2 = 0.49, r,3 = 0.32, r,4 = 0.44, r23= 0.28, r24 = 0.39, and r34= 0.22. intention were not affected by repetition or repetitionrelated interactions. These results do not provide evidence to support H3 and the curvilinear relationship between frequency of exposure and relevant attitude criteria for a new product. One possible explanation for the results is the existence of distinct and different curvilinear relationshipsfor the different treatmentcombinations which when aggregateddo not produce a curvilinearmain effect due to repetition. This explanation seems to be supported by an ad length by repetition interaction for purchase intention which approaches significance (F(2,118) = 2.43; p = 0.09). As shown in Figure 2, the shorter version of the commercial produced more favorable purchase intentions for both knowledge groups as the frequency of exposure increased. The increased opportunity to elaborate provided by repetition appears to have enhanced receivers' feelings toward the product. Repeated exposure to the longer version of the commercial had a different effect. For both knowledge levels, the 90-second commercial tended to produce more "kinked" profiles reflecting a decrease in purchase intention as exposure frequency increased from three to five exposures. These trends are interesting and meaningful in terms of the two-factor perspective. They suggest that increases in the opportunity to elaborate, up to moderate levels, may indeed enhance the persuasiveness of television commercials. At excessive levels of opportunity, however, the persuasiveness of the advertisement declines. Though the ad length by repetition interaction for purchase intention is interesting and meaningful, similar interaction patterns are not observed for the other attitude criteriain the study and hence the overall conclusion must be that H3 is not supported. Cognitive Elaborations The cognitive elaboration perspective suggests that "content-relevant" elaborations show differential patterns across exposure frequencies. Following the conceptualizationof "content-relevant"elaborations used by JOURNAL OF MARKETING FEBRUARY 1986 RESEARCH, 56 Table 2 ANALYSES OF VARIANCE FORATTITUDE MEASURES Ao Source Knowledge(K) Repetition(R) Ad length(L) Kx R Kx L Rx L Kx Rx L p < 0.05. PI F 0.92 0.24 0.48 0.40 0.73 0.69 1.30 SS 1.88 0.99 0.98 1.63 1.49 2.83 5.33 d.f. 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 SS 0.17 5.65 4.29 1.08 3.26 13.51 2.68 CacioppoandPetty(1980), we initiallycategorizedsubjects' elaborationsas either positively valenced, negatively valenced,or neutral.A total of 839 thoughts,or an averageof 6.45 thoughtsper subject, were categorized.Forty-sevenpercentof these thoughtscarriedpositive valencesand 35%were negative.Analysesof varianceperformedon the frequenciesof positive, negative, andneutralresponsesshow no main effects due to repetition,knowledgeability,or ad length.The higherorder interactionsdo not approachsignificancenor do they suggestmeaningfulpatternsof cell meanssimilarto the purchaseintentionpatternsdiscussedbefore. A furtherexaminationof the distributionof elaboration responsesusing the content-basedcoding scheme providedinsightinto whatconstitutes"topicrelevancy" in an advertisingcontext. Product-related responsesaccountfor 40.4% of all elaborationsgenerated,whereas Ad F 0.06 1.02 1.54 0.19 1.17 2.43 0.48 SS 0.44 6.35 1.78 0.06 8.38 5.44 1.89 Acompany F 0.24 1.73 0.97 0.02 4.56a 1.48 0.52 SS 5.55 0.49 1.95 2.54 4.83 0.82 1.37 F 5.17' 0.23 1.82 1.18 4.50a 0.39 0.64 ad-relatedthoughtsconstitute47.3% of all thoughts.Of the total numberof ad-relatedthoughts,25% are repetition-related.Interestingly,curiosity statements, primarilyaboutthe new product,accountfor 17%of the total numberof elaborations.These data suggest that withinan advertisingcontextthe major"topic-relevant" elaborationsinclude responses related to product, ad, repetition,and productcuriosity. To assess how these more specific content elaborations may have been influenced by the experimental treatments,we performedseveral analysesof variance. First,an ANOVA on the net valence index for productrelatedelaborations(i.e., the numberof positiveless the numberof negative product-relatedresponses)did not exhibitany treatmenteffects. A significantlengthmain effect was observed,however, for the numberof product-relatedcuriosityresponses(F(1,118) = 4.49, p < Figure 2 BYFREQUENCY AND COMMERCIAL LENGTH INTENTION OF EXPOSURE, PURCHASE RECEIVER KNOWLEDGE, Low Knowledge C 0 C High Knowledge 3.5 t 3.5 - 3.0 - 3.0 - 90 seconds 2.5 + 2.5 - c 0 C 0 2.0 30 90 seconds 2.0130 1.5- 1.5I I II I 3 1 3 II I I I iI 5 1 3 5 Frequencyof Exposure Frequency of Exposulre THEORY WITHIN ADVERTISING TWO-FACTOR 57 0.05). The 30-second version of the commercialproducedmanymorecuriositythoughtsthandid the 90-second version. The 90-second version showed a larger numberof usage vignettesdramatizingthe uses andbenefits of the new camera. This increased information transmissionmost likely accounts for the decrease in curiositystatementsas a largernumberof recipientquestions may have been answered. Second, the net valence index for ad-relatedreresponses,showed sponses,exclusiveof repetition-related a knowledgeby repetitionby length three-wayinteraction (F(2,118) = 3.59; p < 0.05). As can be observed in Figure3, the ad-relatedresponsesfor the low knowledge subjects became more positive as exposure frequency increased,with the rate of increasegreaterfor the longer ad version. As the opportunityto elaborate increased,ad-relatedelaborationappearsto have become more positive. For the high knowledgeviewers, in contrast,it was the shorterversionof the commercial which resultedin more positive ad-relatedresponsesas exposureincreased.The longer version inducedan inverted-Upatternwith the net valencebecomingnegative for the highest level of exposure.That is, for the high knowledgegroupunderconditionsof highestelaboration opportunitythe ad-relatedelaborationbecamenegative. Thus,the patternof elaborationswithrespectto the commercialis meaningfulandconsistentwith the two-factor perspective. MediatingRole of Elaborations To explorethe potentialmediatingrole of the contentspecific elaborationson the various attitudes, several stepwiseregressionssimilarto the Mitchell and Olson ad(1981)analyseswereperformed.Net product-related, indiceswereusedas predictors related,repetition-related of attitudetowardthe product(Ao), purchaseintention (PI), and attitude toward the ad (Aad). Net product-related elaborationsare found to be the primarypredictorsof bothAo andPI (Table3). Also adrelatedelaborationscontributesignificantlyto the predictionof receivers'attitudetowardthe productbeyond thatexplainedby product-related elaboration.However, they do not contributeto the predictionof purchaseintent. These findingsreplicateMitchell and Olson's results and suggest that thoughad-relatedresponsesmay transferto receivers'attitudestowardthe productthey Figure 3 NETINDEXOF AD-RELATEDCOGNITIVERESPONSES(EXCLUDINGREPETITION-RELATED RESPONSES) BY FREQUENCY OF EXPOSURE, RECEIVER AND COMMERCIAL LENGTH KNOWLEDGE, LowKnowledge High Knowledge 3.0 3.0 2.0 2.0 U) 0 C 90 seconds / ._ O /30 secon3 Is U) 1.0 1.0d 30 seconds o C 30 seconds 'I 0 0) 0 x 1 la -1.0 I I 3 5 Frequencyof Exposure I 01 -1.0 90 second s \1 3 Frequencyof Exposure JOURNAL OF MARKETING FEBRUARY 1986 RESEARCH, 58 Table 3 AND AD CRITERION PRODUCT VARIABLES REGRESSION MODELS PREDICTING (beta coefficientsand F-values) Criterion variable Step Att product(A,,) 1 0.37027 (20.34) 2 0.34461 (19.59) 0.34823 (19.72) 3 Purchase intention (PI) I 2 3 Att ad (Ad) Net product index 3 Net repetition index R2 0.14 0.31411 (16.27) 0.31493 (16.25) 0.24 -0.03978 (0.26)" 0.24 0.13 0.36566 (19.76) 0.35538 (18.37) 0.35032 (17.98) 0.12576 (2.35) 0.12462 (2.29)" 0.19453 (7.31) 0.19060 (6.92) 0.55609 (57.30) 0.54021 (56.36) 0.53932 (55.87) 1 2 Net ad index 0.15 0.05565 (0.46)" 0.15 0.30 0.35 0.04319 (0.36). 0.35 'Not significant at < 0.01. are not a substantial determinant of purchase intention. Last, the regression analyses show that repetition-related elaborations do not contribute to an explanation of the variation in A, and PI beyond that accounted for by the product- and ad-related thoughts. Thus, Hs, which proposes a mediating role for repetition-relatedelaboration, is rejected. The predictors of attitude toward the ad also were examined. As might be expected, ad-related elaborations are the major determinants of Aad. Product-related responses do have a statistically significant role, but the size of the contribution must, for all practical purposes, be considered minimal. Repetition-related elaborations did not bias the formation of attitude toward the ad. CONCLUSIONS Discussion Two general objectives guided our research. The first was to investigate whether the positive learning and negative tedium processes presumed by the two-factor theory to underlie message repetition effects appropriately describe viewers' responses to repeated exposure to a new-product television commercial. The second was to explore whether additional manipulations of elaboration opportunity due to receiver knowledge and commercial length would moderate attitude formation. In terms of the first general objective, the results suggest that repeated exposures increase viewers' familiarity with both the new product and the commercial. Recall of ad content also increases with frequency of exposure. Overall, these findings are consistent with the hypothesized behavior of the first factor in the two-factor theory. Increased exposure to a stimulus allows the receiver to experience greater learning, overcome uncertainties about the stimulus, and form a reaction to it. Direct evidence also is obtained for the hypothesized development of a tedium/reactance response to repeated exposure to the commercial. The frequency of negative repetition-relatedelaboration increased with increases in repetition, and viewers' attitude toward watching thecommercial again became more negative as exposure frequency increased. Thus, support is found for the operation of the second factor of the two-factor theory. Strong support is not found for the hypothesized curvilinear relationship between exposure frequency and attitude formation toward the novel product and commercial. The repetition effect on attitudes was not observed, even though the experiment's level of statistical power to detect effects at a Type I error rate of 5% is comparableto that of earlier experiments (Cohen 1977; Sawyer and Ball 1981).2 Two-factor theory postulates this relationship to be the net result of the two opposing factors. In our study, however, the two factors are found not to be additive. Though an increase in learning was observed across moderate levels of repetition, the increase in learning did not in turn increase affect. Thus, stimulus learning is not necessarily related to affective reactions. At higher levels of repetition the development of tedium was observed but this tedium did not bias at- 'The mean statistical power of the experiment to detectf = 0.10, f = 0.25, and./ = 0.40 at alpha of 0.05 (0.10) is 0.17 (0.27), 0.73 (0.82), and 0.99 (> 0.99), respectively (Cohen 1977). 59 THEORY TWO-FACTOR WITHINADVERTISING titudeformation.Overall, then, sufficientevidence for supportinga two-factortheoryexplanationof repetition effects withinan advertisingcontext is not providedby our data. The lack of transferenceof negative tediumrelatedreactionsto attitudetowardthe productor attitudetowardthe commercialin the advertisingcontextis particularlyinteresting.Viewersappearto separatetheir negativefeelingstowardseeingthe commercialagainfrom theirotherattitudes.Viewers'beliefs aboutthe advertisers' persuasive intent, overzealousness, poor media planning,and otherrelatedexternalfactorsmay be responsiblefor this separation. The secondgeneralobjectiveof ourresearchinvolved examiningthe hypothesizedrole of elaborationopportunity. Despite strong manipulationsof exposure frequency and ad length, receivers' attitudetoward the productdid not exhibitthe hypothesizedeffects. The increasedopportunityto elaborateprovidedby repeated exposuresto the longercommercial,even for individuals highly knowledgeableabout the productclass, did not enhancethe favorabilityof the attitudes. Perhapsin an advertisingcontextthe formationof an initialattitudetowarda new productor a new commercial requiresonly a limited amountof cognitive processing on the part of the consumer,and thereforean increasedopportunityto elaboratedoes not markedlyenhance recognitionof arguments'cogency and message implicationsas is the case in the clearly counterattitudinal messages used in social psychologyexperimental contexts. An alternativeand/or complementaryexplanationfor these findingsis thatfor the type of consumer productfeaturedin the test commercial,productattitudes, once formed, may be enhancedor changedonly as a resultof the acquisitionof additional,moredetailed information.This informationcould come from either external sources (e.g., salespersons, word of mouth, readingtest reports,etc.) or directexperience(i.e., trial) (Smithand Swinyard1982). Thoughthe between-groupanalysesdo not supportthe elaborationopportunityconcept,the regressionanalyses show message elaborationsto be indicativeof attitude formation. The ad-content-basedcoding scheme for classifyingviewers'responsesprovidesan improvedbasis for addressingthe issue of how elaborationsduring exposureaffect various attitudecriteria. Our findings evidence for the Mitchelland Olprovidecorroborating son (1981) suggestionthat product-related elaborations arenotthe only mediatorsof advertisingeffects on brand attitude.We show that both product- and ad-related thoughtsinfluence attitudetoward the product. Additional research employing the content-based coding scheme is needed to develop a betterunderstandingof the relevantmediatorsof repetitioneffects withina new productadvertisingcontext. Giventhe resultsof our studyand similarresultsfrom the studies by Belch (1982) and Mitchell and Olson (1977), evidenceappearsto be accumulatingwhichcasts doubton the appropriateness of the traditionalinverted- U hypothesesfor describingnew product advertising repetitioneffects. Theoreticalaccountsof repetitioneffectsobservedin massedor successiveexposuresto novel nonsensestimuliandcounterattitudinal messagesappear notto be robustframeworksfor describingtelevisionaudience's responsesto repeatedcommercialexposures. Clearlymore researchis needed to assess this position and determinewhetherthe two-factorperspectiveis indeed potentiallyuseful (cf. Sawyer 1981). Limitations Thoughthe use of professionallyprepared,novel television commercialsin our studyrepresentsan improvement in mundanerealityover previousstudies, several limitationsmust be mentioned.First, the highest exposurelevel used in the studymay be consideredexcessive for a less thanone hourprogram.Indeed,for established productssuch exposurepatternsare likely to be uncommon. For new productlaunchingcampaigns,however, suchlevels may not be totallyinconsistentwith viewers' exposureexperienceduringa televisionviewing session. A secondconcernis relatedto the 90-second version of the launchingad. Though this commercialactually was used to introducethe KodakDisc cameraand the ad lengthmay be particularly effective greater-than-usual in the introductionof new products,the 90-secondcommerciallengthis not the industrystandard.Thereforeany generalizationsabout the effects of commerciallength mustbe undertakenwith care. A final aspect of the study which may be explored furtherin futureresearchis the effects of the commercial receptionenvironmenton immediatecognitive elaborations.The small-grouplaboratoryreceptionenvironment in whichoursubjectsoperatedis not identicalto the home viewingenvironmentand may have enhancedreceivers' processingmotivationand opportunity.In a home TVviewingenvironmentfactorsmay be operatingwhichrestrictcognitive elaborationsand responses (cf. Wright 1981). Further Research One issue exploredin our study involvedthe explicit measurementof viewers' tedium/reactancecreatedby repeatedexposureto the sametelevisioncommercial.We foundthat tediumdid not bias product-related elaborations, productattitude,and purchaseintention.Assessment of viewer's attributionsaboutthe causes and implicationsof theirtedium/reactanceresponsestherefore is needed, particularlygiven the crucialrole of tedium in the two-factormodels. The issue of what constitutesappropriateaffect criteriain an advertisingcontextappearsto be an important one. Past advertisingstudies used measuresof attitude towardthe productandpurchaseintention,whichon the surfaceappearto be logical extentionsof the criteriaemployed in the social psychologicalstudies. In our study these measuresplus measuresof attitudetowardthe ad and manufacturer were used becauseviewers are likely 60 to distinguish among product-related feelings and feelings toward the ad and toward the manufacturer.Indeed, the results of the study suggest that these criteria behave ratherindependently and do not share the same treatment effects. It remainsto be explored in future studies whether the formation of these separate attitudes is based on similar underlying processes. Additional information on this issue would provide insight on the question of when and how ad-relatedresponses and attitudesaffect brandchoice (cf. Shimp 1981). A third issue is the need for a cognitive response coding scheme which would be appropriatefor an advertising context. We found that an extended coding scheme could be used to assess the role of repetition and adrelated elaborations in affecting product attitude. Future research might consider more complex and/or more refined coding schemes to explore further whether viewers' elaboration becomes biased or changes across exposure frequency (cf. Krugman 1972). A final, related issue is the mediating role of receiver's elaborations. In our study regression analyses using the content-based elaborations indicate that these responses were significant predictors of the appropriateattitude measures. It is important to note, however, that the frequencies of these specific content responses did not indicate treatment effects parallel to the effects observed in the respective attitude criteria. Though this finding is similar to those in other advertising studies (e.g., Calder and Sternthal 1980), it suggests that the issue of whether or not cognitive responses are attitudecontent-specific mediators remains important and remains to be resolved. REFERENCES Aaker, D. A. (1975), "ADMOD:An AdvertisingDecision Model,"Journalof MarketingResearch,12 (February),3745. Belch, G. E. (1981), "An Examinationof Comparativeand NoncomparativeTelevision Commercials:The Effects of ClaimVariationand Repetitionon CognitiveResponseand MessageAcceptance,"Journalof MarketingResearch, 18 (August),333-49. (1982), "TheEffects of TelevisionCommercialRepetitionon CognitiveResponse and Message Acceptance," Journalof ConsumerResearch,9 (June),56-66. Berlyne,D. E. (1970), "Novelty, Complexity,and Hedonic Value,"Perceptionand Psychophysics,8, 279-86. Bettman,J. R. and C. W. Park (1980), "Effects of Prior KnowledgeandExperienceandPhaseof the ChoiceProcess on ConsumerDecisionProcess:A ProtocolAnalysis,"Journal of ConsumerResearch,7 (December),234-48. Bogart,L. and C. Lehman(1983), "TheCase of the 30-second Commercial,"Journal of AdvertisingResearch, 23 (February/March),11-20. Cacioppo,J. T. andR. E. Petty(1979), "TheEffectsof Message RepetitionandPositionon CognitiveResponse,Recall and Persuasion,"Journal of Personalityand Social Psychology, 37, 97-109. and (1980), "Persuasivenessof Communicationsis Affectedby ExposureFrequencyandMessageQual- JOURNAL OF MARKETING FEBRUARY 1986 RESEARCH, ity: A Theoreticaland EmpiricalAnalysisof PersistingAt- titude Change," in Current Issues and Research in Advertising,J. H. LeighandC. R. Martin,eds. Ann Arbor, MI: Universityof Michigan,97-122. Calder,B. J., C. A. Insko, and B. Yandell(1974), "TheRelation of Cognitiveand MemorialProcessesto Persuasion in a Simulated Jury Trial," Journal of Applied Social Psy- 62-93. chology,4 (January-March), and B. Sternthal(1980), "Television Commercial Wearout:An InformationProcessing View," Journal of Marketing Research, 17 (May), 173-86. Cohen, J. (1977), Statistical Power Analysis for the Behav- ioral Sciences. New York:AcademicPress. Edell,J. A. andA. A. Mitchell(1978), "AnInformationProcessing Approachto Cognitive Response," in Research Frontiers in Marketing:Dialogues and Directions, S. C. Jain, ed. Chicago:AmericanMarketingAssociation, 178-83. Gardner,M. P. (1983), "AdvertisingEffectson AttributesRecalledandCriteriaUsed for BrandEvaluations,"Journalof Consumer Research, 10 (December), 310-18. Ginter,J. L. (1974), "An ExperimentalInvestigationof Attitude Change and Choice of a New Brand,"Journal of Marketing Research, 11 (February), 30-40. Gorn,G. J. andM. E. Goldberg(1980), "Children'sResponse to RepetitiveTelevision Commercials,"Journal of Consumer Research, 6 (March), 421-4. Krugman,H. E. (1972), "Why Three ExposuresMay Be Enough," Journal of Advertising Research, 3 (December), 11-14. Little,J. D. C. andL. M. Lodish(1969), "A MediaPlanning Calculus," Operations Research, 17 (January), 1-35. of a Lutz, R. J. and S. C. MacKenzie(1982), "Construction DiagnosticCognitiveResponseModel for Use in Commercial Pretesting," in Straight Talk About Attitude Research, M. J. Naples and J. S. Chasin, eds. Chicago:American MarketingAssociation,145-56. Mitchell,A. A. and J. C. Olson (1977), "CognitiveEffects of Advertising Repetition," in Advances in Consumer Re- search, Vol. 4, W. D. Perreault,Jr., ed. Atlanta:Associationfor ConsumerResearch,213-20. and (1981), "AreProductAttributeBeliefs the Only Mediatorof AdvertisingEffects on BrandAttitude?" Journal of Marketing Research, 18 (August), 318-32. Olson, J. C., D. Toy, and P. Dover (1982), "Do Cognitive ResponsesMediatethe Effects of AdvertisingContenton Cognitive Structure?"Journal of ConsumerResearch, 9, 245- 62. Ray, M. L. andA. G. Sawyer(1971a), "Repetitionin Media Models:A LaboratoryTechnique,"Journal of Marketing Research,8 (February),20-9. and (1971b), "BehavioralMeasurementfor MarketingModels: Estimatingthe Effects of Advertising Repetitionfor Media Planning,"ManagementScience, 18 (4-2), 73-89. , andE. C. Strong(1971), "FrequencyEffects Revisited," Journal of Advertising Research, 11, 14-20. Sawyer,A. G. (1981), "RepetitionandCognitiveResponse," in Cognitive Responses in Persuasion, R. E. Petty, T. Os- trum,andT. C. Brock,eds. Hillsdale,NJ: Earlbaum,23762. and A. D. Ball (1981), "StatisticalPowerand Effect Size in Marketing Research," Journal of Marketing Re- search, 18 (August),275-90. Effects in Adverand S. Ward(1979), "Carry-Over WITHIN ADVERTISING THEORY TWO-FACTOR 61 in Researchin Marketing,Vol. II, tisingCommunication," J. N. Sheth, ed. Greenwich,CT: JAI Press, 259-314. Shimp,T. (1981), "AttitudeTowardthe Ad as a Mediatorof ConsumerBrandChoice," Journal of Advertising,10 (2), 9-15. Silk, A. J. and J. G. Vavra (1974), "The Influenceof Advertising Affective Qualities on Consumer Response," in BuyerConsumerInformationProcessing,G. D. Hughesand M. L. Ray, eds. ChapelHill, NC: Universityof NorthCarolina Press, 157-86. ReSmith, R. E. and W. R. Swinyard(1982), "Information sponseModels:An IntegratedApproach,"Journalof Marketing,46 (Winter),81-93. Stang,D. J. (1975), "TheEffectsof MereExposureon Learning and Affect," Journal of Personalityand Social Psychology, 31, 7-13. Webb, P. H. (1979), "ConsumerInitialProcessingin a DifficultMediaEnvironment," Journalof ConsumerResearch, 6 (December),225-36. Wells, D. W., C. Leavitt, and M. McConville(1971), "A ReactionProfilefor TV Commercials,"Journalof Adver- Shaped by tisingResearch, 11 (December),11-17. Wheatley,J. J. (1968), "Influenceof CommercialLengthand Position,"Journalof MarketingResearch, 5 (May), 199202. Winter,F. W. (1973), "A LaboratoryExperimentof Individual AttitudeResponseto AdvertisingExposure,"Journalof MarketingResearch, 10 (May), 130-40. Wright,P. L. (1973), "The Cognitive Processes Mediating Acceptance of Advertising,"Journal of MarketingResearch, 10 (February),53-67. (1980), "MessageEvokedThoughts:PersuasionResearch Using Thought Verbalizations,"Journal of ConsumerResearch,7 (September),151-75. (1981), "CognitiveResponsesto Mass Media Advocacy," in CognitiveResponsesIn Persuasion,R. E. Petty, T. Ostrom,andT. C. Brock,eds. Hillsdale,NJ:Earlbaum, 263-83. Zajonc,R. B. (1968), "TheAttitudinalEffects of Mere Exposure," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Monograph,9 (2), Part2. the s for'80sts Principles of Marketing Secotd Edition Thomas C. Kinnear, University of Michigan Kenneth L. Berhardt, Georgia State Uiversity Available Now 832 pages,hardbound, Manillustrated,with Instructor's ual, ResourceBook, Study Guide, Case Book, Transparencies, TestBank, VideotapeProgram, ComputerizedTest Bank, and DIPLOMA Are you really satisfied with '60s and '70s analyses of '86s problems? Most introductory texts offer just that. Kinnear and Bernhardt's Princples of Marketing is the only successful new marketing text that has been truly shaped by the '80s. If you used the First Edition of thispopuar text, we know that you will be even more impressed with the Second Edition. A few Second Edition highlights: * More material on strategic marketing More on marketing and public policy More on industial buying behavior ? More on marketing and the external environment ?0New case applications New interviews with marketing practitioners New "Marketing in Action sections Expanded and purposeful use of full-color illustrations * Hundreds of new in-text examples For further information write Meredith Hellestrae, Department SA-JMR, 1900 EastcLake Avenue, Glenview, Illinois 60025 Scott, :Fore:an and Company