RESEARCH ARTICLE Park, Nigeria

advertisement

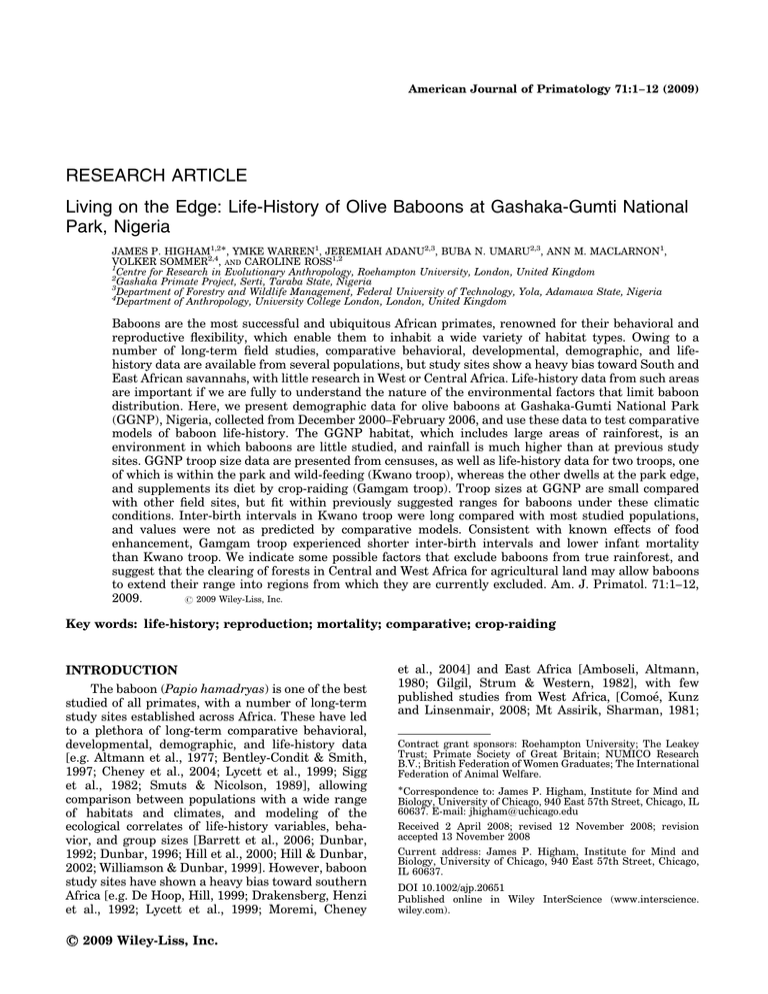

American Journal of Primatology 71:1–12 (2009) RESEARCH ARTICLE Living on the Edge: Life-History of Olive Baboons at Gashaka-Gumti National Park, Nigeria JAMES P. HIGHAM1,2, YMKE WARREN1, JEREMIAH ADANU2,3, BUBA N. UMARU2,3, ANN M. MACLARNON1, VOLKER SOMMER2,4, AND CAROLINE ROSS1,2 1 Centre for Research in Evolutionary Anthropology, Roehampton University, London, United Kingdom 2 Gashaka Primate Project, Serti, Taraba State, Nigeria 3 Department of Forestry and Wildlife Management, Federal University of Technology, Yola, Adamawa State, Nigeria 4 Department of Anthropology, University College London, London, United Kingdom Baboons are the most successful and ubiquitous African primates, renowned for their behavioral and reproductive flexibility, which enable them to inhabit a wide variety of habitat types. Owing to a number of long-term field studies, comparative behavioral, developmental, demographic, and lifehistory data are available from several populations, but study sites show a heavy bias toward South and East African savannahs, with little research in West or Central Africa. Life-history data from such areas are important if we are fully to understand the nature of the environmental factors that limit baboon distribution. Here, we present demographic data for olive baboons at Gashaka-Gumti National Park (GGNP), Nigeria, collected from December 2000–February 2006, and use these data to test comparative models of baboon life-history. The GGNP habitat, which includes large areas of rainforest, is an environment in which baboons are little studied, and rainfall is much higher than at previous study sites. GGNP troop size data are presented from censuses, as well as life-history data for two troops, one of which is within the park and wild-feeding (Kwano troop), whereas the other dwells at the park edge, and supplements its diet by crop-raiding (Gamgam troop). Troop sizes at GGNP are small compared with other field sites, but fit within previously suggested ranges for baboons under these climatic conditions. Inter-birth intervals in Kwano troop were long compared with most studied populations, and values were not as predicted by comparative models. Consistent with known effects of food enhancement, Gamgam troop experienced shorter inter-birth intervals and lower infant mortality than Kwano troop. We indicate some possible factors that exclude baboons from true rainforest, and suggest that the clearing of forests in Central and West Africa for agricultural land may allow baboons to extend their range into regions from which they are currently excluded. Am. J. Primatol. 71:1–12, 2009. r 2009 Wiley-Liss, Inc. Key words: life-history; reproduction; mortality; comparative; crop-raiding INTRODUCTION The baboon (Papio hamadryas) is one of the best studied of all primates, with a number of long-term study sites established across Africa. These have led to a plethora of long-term comparative behavioral, developmental, demographic, and life-history data [e.g. Altmann et al., 1977; Bentley-Condit & Smith, 1997; Cheney et al., 2004; Lycett et al., 1999; Sigg et al., 1982; Smuts & Nicolson, 1989], allowing comparison between populations with a wide range of habitats and climates, and modeling of the ecological correlates of life-history variables, behavior, and group sizes [Barrett et al., 2006; Dunbar, 1992; Dunbar, 1996; Hill et al., 2000; Hill & Dunbar, 2002; Williamson & Dunbar, 1999]. However, baboon study sites have shown a heavy bias toward southern Africa [e.g. De Hoop, Hill, 1999; Drakensberg, Henzi et al., 1992; Lycett et al., 1999; Moremi, Cheney r 2009 Wiley-Liss, Inc. et al., 2004] and East Africa [Amboseli, Altmann, 1980; Gilgil, Strum & Western, 1982], with few published studies from West Africa, [Comoé, Kunz and Linsenmair, 2008; Mt Assirik, Sharman, 1981; Contract grant sponsors: Roehampton University; The Leakey Trust; Primate Society of Great Britain; NUMICO Research B.V.; British Federation of Women Graduates; The International Federation of Animal Welfare. Correspondence to: James P. Higham, Institute for Mind and Biology, University of Chicago, 940 East 57th Street, Chicago, IL 60637. E-mail: jhigham@uchicago.edu Received 2 April 2008; revised 12 November 2008; revision accepted 13 November 2008 Current address: James P. Higham, Institute for Mind and Biology, University of Chicago, 940 East 57th Street, Chicago, IL 60637. DOI 10.1002/ajp.20651 Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience. wiley.com). 2 / Higham et al. Shai hills, Depew, 1983] and none from central Africa. As a consequence, baboons are well studied in savannah grasslands, whereas relatively little is known about baboon ecology in some other habitats, particularly forest, into which baboons penetrate to various extents at the edges of their distribution. Here, we present life-history and group size estimates for wild olive baboons (P. hamadryas anubis) [Rogers, 2000] at Gashaka-Gumti National Park (GGNP), Nigeria, and set these data in the context of comparative baboon socio-ecology. This site is a geographical, habitat and climatic outlier compared with other baboon sites, and as such our data are of particular interest for understanding the role of the environment in influencing subspecific variation in baboon ecology. Comparative studies that investigate variation in baboon life-history and group size tend to focus on variation in a few key climatic variables, such as average temperature, mean annual rainfall, and rainfall seasonality [Barrett et al., 2006; Dunbar 1992, 1996; Hill et al., 2000; Williamson & Dunbar, 1999]. Rainfall is a reliable indicator of plant productivity, and therefore of resource availability, in both tropical [Deshmukh, 1984] and temperate [Knapp & Smith, 2001] grasslands, and may be key in indirectly determining female condition, and hence fertility [e.g. orang-utans, Knott, 2005]. Consistent with this, Lycett et al. [1999] showed that patterns of rainfall correlate positively with the likelihood of conception in baboons at Drakensberg, and suggested that food availability mediates this link via female condition, although seasonal changes in temperature may also be important. There is also evidence that periods of drought reduce the likelihood of conception and increase the likelihood of fetal loss at Amboseli [Beehner et al., 2006], and food scarcity has been linked to increases in infant and juvenile mortality at Amboseli [Altmann et al., 1985], and De Hoop [Barrett & Henzi, 2000]. The first major comparative analyses of baboon ecology came from Dunbar [1992, 1996; Williamson & Dunbar, 1999] who used annual temperature, rainfall, and rainfall diversity to explain likely minimum feeding and traveling requirements in different environments, and then used the constraints posed by these to investigate the maximum group sizes that could be maintained when the available time is directed toward social relationships. These comparative analyses of group size and activity were followed by a comparative model of inter-birth intervals. Hill et al. [2000] used data from 14 field sites (of which 13 were in East or southern Africa), and showed that the number of group females and mean annual temperature explain 84% of the variance in inter-birth intervals across baboon populations, with number of females showing a significant quadratic relationship with rainfall. However, this inter-site analysis found no relationship between inter-birth interval and Am. J. Primatol. absolute measures of rainfall. In a separate comparative analysis, Barrett et al. [2006], taking data from ten East and southern African sites, correlated inter-birth intervals and infant mortality with an index of habitat productivity and seasonality. They argued that in less productive, but more seasonal habitats, baboon populations are more likely to have seasonal birth peaks, reducing the likelihood that infant weaning occurs at a difficult time for infants to sustain independence [Barrett et al., 2006]. Thus, rainfall is an important correlate of life-history in baboons, but seasonality of rainfall may be as important as total annual rainfall. Although there are a large number of baboon field sites from which long-term data are available for forming and testing comparative models, there are few such studies from wet, forested sites. Olive baboons are the most common type found in forests, although this may be a temporary expansion [Kingdon, 1997], and all baboons appear to be excluded from most of the wet, closed forests of Central and West Africa. Kingdon [1997] speculated that ecological pressures, such as disease and competition, may limit the success of baboons in these environments, and some authors have suggested that the opening up of forests for agriculture [Tappen, 1960; Greenhood, 1971], may have enabled baboons to extend their range into areas from which they would otherwise have been excluded. However, an understanding of the factors that may limit the distribution of baboons in the equatorial forest zone is currently lacking. Our study helps fill this need, by presenting the first life-history and group size data for forest baboons in west-central Africa. We provide data for two troops at GGNP, one of which is wildfeeding (Kwano troop), whereas the other (Gamgam troop) supplements its diet via crop-raiding [Warren et al., 2007]. Many studies have demonstrated that the consumption of anthropogenic foodstuffs can have major effects on life-history parameters and demography in primates [e.g. chimpanzees, Goodall, 1983; Japanese macaques, Mori et al., 1997; Sugiyama and Oshawa; Indian langurs, Borries et al., 1991; Barbary macaques, Fa, 1984; baboons, Altmann et al., 1978; Strum, 1991], and we look for such relationships here. In setting data from the wildfeeding Kwano troop into context, we investigate whether our data fit with predictions from baboon models and comparative relationships suggested by Dunbar [1992, 1996], Hill et al. [2000], and Barrett et al. [2006]. METHODS Study Site GGNP is on the eastern border of to the southern edge of western P. hamadrayas anubis distribution habituated two troops, one (Kwano Nigeria, close extension of (Fig. 1). We troop) inside Life-History of Wild Olive Baboons / 3 the park at the Gashaka Primate Project field station at Kwano [Sommer et al., 2004], and the other 10 km away on the edge of the park, close to the village of Gashaka, along the banks of the river Gam Gam (Gamgam troop). Both sites lie in the forest–grassland transition zone, and hence contain some elements of both habitat types. However, Kwano troop home range has substantially more lowland and gallery rainforest (65%) than guinea savannah woodland (35%), whereas the reverse is true for Gamgam troop [15% forest, 70% guinea savannah woodland, 15% crop-land and elephant grass; Warren, 2003]. Gamgam troop’s home range is consequently much more open than Kwano troop’s, receives much greater and more intense grass burning during the dry season, and is also heavily grazed by the cattle of nomadic Fulani at certain times of year. In addition to these habitat differences, Gamgam troop regularly supplements its diet with maize and a variety of other crops taken directly from farms along the banks of the river [Warren et al., 2007]. Among baboon field sites, GGNP is an extreme outlier with regards to rainfall, and Kwano represents the wettest of all baboon study sites to date. Average annual rainfall (x ¼ 2022 mm for 2001–2006, data from Gashaka Primate Project weather station) is around 3.5 SDs above the mean of the 14 baboon sites listed in Hill et al. [2000] (x ¼ 693 mm, SD 5 399). Kwano’s mean temperature, 26.41C, is also high, being greater than 1 SD above the mean in Hill et al. [2000] (x ¼ 22:1 C, Fig. 1. Position of Gashaka-Gumti National Park (GGNP, square) with respect to 31 other baboon field sites (circles) used by Dunbar [1992] to develop his model of baboon behavior. Adapted from Dunbar [1992], with approximate olive baboon range (gray shading) added from Kingdon [1997]. The olive baboon range is bounded in the North-East and South-East by the presence of hamadryas and yellow baboons respectively, in the North by the sahara, in the West by the presence of guinea baboons, and in the South and South-West by high rainfall and associated closed forests. GGNP is close to the southern edge of the western extension of the olive baboon range. SD 5 3.8). The habitat of GGNP, especially the large closed forests in Kwano troop’s home range, is also unusual for baboons, which are found more commonly in savannah habitats, and are certainly much better studied in such environments. Troop Sizes Censusing was undertaken to obtain data on baboon troop sizes at GGNP between March and July 2006 [as in Altmann et al., 1985; Samuels and Altmann, 1991]. Censusing of troops (total n 5 22) by an experienced field assistant took place around the Kwano, Gashaka, and Selbe areas. Three counts of individuals in age–sex classes in each troop were taken, each separated by a minimum of 30 min. Home range areas and distinguishing features of individuals in troops were noted to prevent accidental re-sampling. Monitoring and Measuring Life-History We started habituation of the two study troops in 2000, and the first birth dates used in our analysis come from December 2000. At the start of the study period, modal Kwano troop size was 28, whereas modal Gamgam troop size was 14. At the start of full data collection in March 2001, all adult troop members were known individually, as were many juveniles and infants. From March 2001 until May 2002, field assistants followed rotating focal individuals from both troops for 8 days a month. From May 2002 until November 2003, field assistants followed focal individuals for 20 days a month in Kwano troop, but there was no regular work undertaken with Gamgam troop, and only an occasional census used to ascertain whether all group members were still present, and whether new infants had been born. Since December 2003, field assistants have attempted to follow focal individuals in both troops for a minimum of 20 days a month, and for up to 26 days a month. As such, records are completely continuous for Kwano troop, but there is less continuity for Gamgam troop. Data collected include the presence or absence of troop members, details of age–sex classes, births, deaths, signs of illness, wounds and female reproductive state according to the following scheme [Higham et al., 2007; 2008]: Lactating—suckling an infant; Pregnant—not cycling and showing the pregnancy signs [Altmann, 1973]; S0—cycling with no swelling; S1—cycling with a small swelling of the ano-genital area (AGA); S2—cycling with a medium–large swelling of the AGA and a small swelling of the Para-Callosal Skin (PCS); S3—cycling with a large swelling of the AGA and full swelling of the PCS. For both troops, a number of life-history parameters were estimated (Table I). Owing to less continuity in data collection for Gamgam troop compared with Kwano troop, (see above) there is Am. J. Primatol. 4 / Higham et al. TABLE I. Definitions of Life-History Parameters Parameter Unit Definition Length of postpartum amenorrhea (PPA) Length of post infant death amenorrhea (PIDA) Duration of cycling (when infant survived) (DC) Post infant death duration of cycling (PIDDC) Gestation length (G) Months Months Months Months Days Cycle length Days Observed inter-birth interval Months Observed inter-birth interval post infant death Months Inter-birth interval Infant mortality Months % Group size No. Time from birth until the first day of sexual swelling Time from infant death until the first day of sexual swelling Duration of cycling from end of PPA to conception Duration of cycling from end of PIDA to conception Using measures of fecal hormones to estimate ovulation date (Higham et al. 2008), time from date of probable conceptive ovulation to birth date Using measures of fecal hormones to estimate ovulation date (Higham et al. 2008), time between successive estimated ovulation dates Inter-birth interval when two consecutive birth dates for a given female are known, and where the first infant survived and was successfully weaned Inter-birth interval when two consecutive birth dates for a given female are known and the former infant died o12 months. For other sites, this figure was calculated by (PIDA1PIDDC1G). When PIDDC was not available, DC was used (PPA1DC1G) Births resulting in death o12 months old as a percentage of all births Modal group size of the troop. less confidence in some of the data. Data are not presented where there is uncertainty about their accuracy; thus sample sizes for Gamgam troop are lower. Age specific mortality was calculated [following Altmann et al., 1977] for infants up to 12 months old only as, for several years of the study, individual identification of juveniles in the two troops was incomplete. We document birth seasonality in both troops, and present a number of other life-history parameters, which focus on the inter-birth interval. Inter-birth intervals have been estimated in very different ways across studies. Altmann et al. [1977] calculated the inter-birth interval by adding together the mean values of each of its constituent parts (length of postpartum amenorrhea, duration of cycling to conception, and gestation length). Other researchers [e.g. Bentley-Condit & Smith, 1997; Sigg et al., 1982] used observed inter-birth intervals only, i.e. the interval between consecutive births, with successful rearing and weaning of the first infant. Lycett et al. [1998] estimated the inter-birth interval by multiplying the number of adult females by the number of monitored years and then dividing by the number of births. Although we follow Altmann et al. [1977], we report the observed inter-birth interval additionally. Estimates are provided of gestation and cycle lengths using ovulation dates estimated from fecal hormones measures [Higham et al., 2008], which are likely to be more accurate than estimates made from observation of sexual swellings. We aimed to collect fecal samples every 1–2 days from individual females for the measurement of fecal estrogen and progestogen levels, and these two hormone metabolite measures were combined to estimate Am. J. Primatol. ovulation dates in individual cycles [see Higham et al., 2008]. When presenting our data, we also give previously published values from several sites that have presented similar and directly comparable data. These sites are Amboseli, Kenya [Altmann et al., 1977; Altmann, 1980]; Mchelelo, Kenya [BentleyCondit & Smith, 1997]; Gilgil, Kenya [Smuts & Nicholson, 1989]; and Erer, Ethiopia [Sigg et al., 1982]. As this sample represents a relatively limited range of the available comparative data, we compare our values for GGNP group sizes and inter-birth intervals from the wild-feeding Kwano troop statistically with multi-group datasets published by Hill et al. [2000] and Barrett et al. [2006], using onesample t-tests (SPSS 15). We then use our data to test previously suggested comparative baboon models and relationships [Barrett et al., 2006; Dunbar, 1992, 1996; Hill et al., 2000]. Comparison of Kwano and Gamgam troop LifeHistory Where sample sizes were sufficient to enable statistical analyses, independent sample t-tests (SPSS 14.0) were used to compare life-history parameters between Kwano and Gamgam troops. We also compare birth-seasonality in the two troops. Testing Comparative Relationships As we estimate infant mortality up to 12 months only (compared with the more common 24 months, see above), and infant deaths in Kwano troop were clustered during the study period, suggesting that Life-History of Wild Olive Baboons / 5 our estimates of mortality may need revision in the future, we do not use our mortality data to test suggested comparative relationships of baboon mortality. In addition, we do not use data from the foodenhanced Gamgam troop in such comparisons. Instead, we focus on testing comparative relationships using inter-birth interval data from the wildfeeding Kwano troop, and troop size data obtained during the census. Dunbar [1992, 1996] and Williamson and Dunbar [1999] published models of baboon behavior that predict maximum ecologically tolerable and minimum ecologically permissible troop sizes for areas with different mean ambient temperatures and mean annual rainfall. We used the published tables of these predictions in Dunbar [1996] to see whether the troop sizes measured in our census fit within Dunbar’s suggested range. We used the points in the table that most closely approximated the climate at Kwano, which were a mean annual rainfall of 2100 mm (compared with 2022 mm for Kwano over the study period), and a mean annual temperature of 251C (compared with 26.41C for Kwano over the study period). We compared our estimates of inter-birth interval with predicted values for our study population derived from Hill et al. [2000], who showed that inter-birth intervals in baboon populations could be predicted by mean temperature and number of troop females, with the relationship described by the following regression equation: lnðIBIÞ ¼ 20:736 2:914 lnðFÞ þ 0:553½lnðFÞ2 8:953 lnðTÞ þ 1:452½lnðTÞ2 where T is the mean annual temperature, and F the mean number of troop females. We used the Kwano mean temperature (26.41C), and the mean number of troop females measured in our GGNP census. We tested the model additionally using mean number of troop females in the Kwano area only. Finally, we looked at the relationship proposed by Barrett et al. [2006] between inter-birth intervals and a measure of habitat productivity, P42t [from le Houréau, 1984 cited in Barrett et al., 2006], which represents the number of months in which precipitation (in mm) is greater than twice the mean annual temperature (in 1C). For Kwano this figure is 7. Barrett et al. [2006] suggested that this index can be related to the inter-birth interval, with a close to significant positive relationship between inter-birth intervals and P42t when the outlying Drakensberg population is removed from the analysis. We investigate whether data from Gashaka are consistent with this proposed relationship or whether, like Drakensberg, Gashaka does not appear to fit this pattern. Research Ethics All research protocols followed were assessed and approved by Roehampton University’s Research Degrees Board, which included ethical approval, and adhered to all legal requirements of both Nigeria and the UK. RESULTS Troop sizes for GGNP are presented in Table II. The mean GGNP troop size is significantly smaller than troop sizes at 14 other study sites [Hill et al., 2000] (t 5 6.22, df 5 13, Po0.001) Table III presents data on life-history of Kwano and Gamgam troops; here we focus on the lifehistory of the wild-feeding Kwano troop. Kwano Life-History Inter-birth intervals at Kwano (29.9 months, calculated from constituent means, see Table I) are long, being significantly longer than the sample of 11 sites given in Barrett et al. [2006] (t 5 3.0, df 5 10, P 5 0.013), and higher than all sites yet studied bar the outlying Drakensberg [38.5, Lycett et al., 1998; Barrett et al., 2006]. Inter-birth intervals are reduced in Kwano troop following infant death (t 5 2.8, df 5 5, P 5 0.036), even given wide variation in the age at which infants died (0–9 months). This reduction comes from a reduction in duration of cycling (t 5 6.2, df 5 10, Po0.001). The observed inter-birth interval of 25.0 months is based on just two observations, owing to high infant mortality in Kwano, and hence few cases in which females with a surviving infant went on to have second offspring, with both birth dates accurately known. Kwano troop suffered high infant mortality compared with other sites (Fig. 2), and most of the nine infant deaths were clustered in time. Four infants died in October 2004, at the peak of the wettest rainy season recorded to date, with 2337 mm, around 16% higher than the Kwano average (x ¼ 2022 mm). We also recorded two infant deaths in January 2003, shortly after a group takeover, in which an immigrant male chased and harassed group females before becoming the new dominant male. TABLE II. Mean Troop Sizes in Three Different Areas of GGNP Troop size Area Kwano Gashaka Selbe Overall Number of females Mean SD Mean SD No. of troops 5 22.3 21.2 19.4 20.7 6.5 3.6 6.5 5.1 5.4 4.5 5.6 5.0 1.0 1.4 0.9 1.2 7 5 10 22 Am. J. Primatol. Am. J. Primatol. 4.0 3.5 2.8 5.1 n/a n/a n/a 185.3 42.3 25.0 13.8 29.9 47% 27d anubis Type 180–188 39–46 23-27 8–21b n/a n/a 26–28 7–17 0–4 10–16 1–8 Range 4 3 2 5 n/a 19c n/a 7 8 5 7 n 1.5 9.3 anubis 188–192 42.3 16.0 – 16.5 6.3% 14–21 – – Mean n/a 2.3 1.2 – n/a n/a n/a 1.0 – 0.7 – SD n/a 41–45 15–17 – n/a n/a 14–21 8–10 – 12 – Range Gamgam troop Data converted from days to months where appropriate. N values given are incidences not females. a Median cycle length. b Wide range owing to variation in age at which infants died. c Total number of known births. d Modal group size throughout study period. e Mean derived from Table II in Altmann (1980). f Mean of three bands that made up Cone Rock Troop in 1974 (236/3). References 4.8 1.5 2.3 2.6 SD 11.3 1.4 12.4 3.4 Mean Postpartum amenorrhea Post infant death amenorrhea Duration of cycling Post infant death duration of cycling Gestation length Cycle length Observed inter-birth interval Post infant death Inter-birth interval Infant mortality Group size Parameter Kwano troop 1 3 4 – n/a 16c n/a 4 – 2 – n [Altmann et al., 1977; Altmann, 1980] cynocephalus 175 32–34 21 10.9 22 33% 45e 12 0.8 4 – Mean Amboseli (Alto’s troop) [Bentley-Condit & Smith, 1997] cynocephalus 181.5 38.9 27.9 12.8 24.5 12% 79.6 14.6 1.9 4.9 – Mean Mchelelo TABLE III. Life-History Parameter Estimates of Kwano and Gamgam Troops, Compared With Some Other Sites [Smuts & Nicolson, 1989] anubis 180.2 42a 25.0 11.8 24.9 22% 115–135 13.4 1.0 5.6 4.9 Mean Gilgil [Sigg et al., 1982] hamadryas – – 24 – – 18% 78.7f 14 1 – 3.5 Mean Erer 6 / Higham et al. 7 7 3 6 1 0 3 3 0 4 3 19 21 4 5 0 No data 0 0 4 4 14 2000–2002 2002–2003 2003–2005 2005–2006 Neither gestation length (t 5 1.1, df 5 3, P 5 0.367) nor cycle length (t5 5 0.2, P 5 0.988) differed between the two troops. Inter-birth intervals were shorter in Gamgam than in Kwano (t 5 6.0, df 5 4, P 5 0.004). Although length of postpartum amenorrhea was shorter in Gamgam compared with Kwano, this was not significant (t 5 0.8, df 5 9, P 5 0.429), and instead, reduced inter-birth intervals were largely the result of reduced duration of cycling (t 5 6.3, df 5 5, P 5 0.002). Although Gamgam troop is smaller than Kwano troop it increased in size by 50% between 2000 and 2006, whereas Kwano troop size remained static (Table IV). Infant mortality in Kwano was high compared with Gamgam (Fig. 2), where the only known infant death o12 months was that of a twin. No adult females have died or disappeared in Gamgam troop since fieldwork began in 2000, though one known adult male death occurred in Gamgam troop in 2005, after a farmer inflicted serious wounds on the individual during crop-raiding. Y. Warren J. Adanu J. Higham E. Ey Comparison of Kwano and Gamgam Troops TABLE IV. Change in Modal Troop Size and Composition Over Four Fieldwork Phases Both of these infant deaths occurred during or after chases of the mothers. Four adult females disappeared in Kwano, including one during the 2004 heavy rains. Disappearances all occurred after females were seen struggling with obvious and debilitating disease symptoms, which included visible external growths on the abdomen, and severe loss of fur. Other females have been observed with symptoms such as heavy fur loss during the study period, but have recovered. On one female disappearance, her infant also vanished, whereas on another, an infant died before the mother disappeared, and on a third a female was heavily pregnant when she disappeared. Adult males Fig. 2. Survivorship curve for Kwano and Gamgam troops, presented with published data from Amboseli [Altmann, 1980], and Mchelelo [Bentley-Condit & Smith, 1997]. The only known infant death o12 months of age in Gamgam was a twin (born 19th August 2004) that died; the other survived. 8 8 4 5 12 Gamgam troop size 10 Subadult females Juvenile Infant 8 Adult Subadult females males 6 Age in months Adult males 4 Kwano troop size 2 Fieldwork years 0 5 4 3 6 0.0 2 1 5 3 Amboseli (Alto's Troop) Mchelelo Gamgam Troop Kwano Troop 0.2 0 1 2 2 Adult Subadult females males 0.4 7 7 6 7 0.6 Study Survivorship 0.8 6 6 6 3 1.0 28 27 26 26 Subadult females Juvenile Infant Life-History of Wild Olive Baboons / 7 Am. J. Primatol. 8 / Higham et al. There is no clear evidence of birth seasonality in Kwano troop with births observed in all months except April (Fig. 3a), but Gamgam troop possibly shows a birth peak 6 months (approximate gestation length) after wet season crop-raiding (Fig. 3b), although sample sizes are too small to test for the significance of this pattern. Testing Comparative Relationships The models developed by Dunbar [1996, following Dunbar, 1992], produce estimates of maximum ecologically tolerable and minimum ecologically permissible troop sizes of 53 and 13 respectively for baboons living in an area with rainfall at 2100 mm per year and a mean ambient temperature of 251C. The troop sizes observed in our census (Table II), as well as our study troop sizes, fall within, but toward the lower end of, the range suggested by Dunbar’s [1996] model. Hill et al.’s [2000] regression model predicts an inter-birth interval of 41.7 months for GGNP baboons, and 38.1 months for Kwano baboons 5 400 Kwano Rainfall Kwano Births Rainfall (mm) 3 200 2 100 Number of known births 4 300 Apr May Jun Jul (a) Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan 0 Feb Month 500 5 4 300 3 200 2 100 1 0 Mar Apr May (b) Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Number of known births Rainfall (mm) Crop raiding Gamgam Rainfall Gamgam Births 400 0 Feb Month Fig. 3. Birth seasonality and rainfall, 2001–2006 for Kwano troop (a) and 2000–2006 for Gamgam troop (b), with periods of cropraiding indicated for the latter. Data are orientated such that the X-axis starts at the beginning of the wet season and ends at the close of the dry season. Am. J. Primatol. DISCUSSION The geographic, habitat, and climatic characteristics of GGNP make troop size and life-history data particularly important for understanding interpopulation differences in baboon life-history. A number of features of GGNP baboons, such as long durations of cycling to conception and small group sizes, differ from characteristics of East and southern African baboon populations. In addition, values for Kwano and Gamgam troops differ, reflecting effects of food enhancement. Troop Sizes Troop sizes at GGNP are significantly smaller than at most other sites studied to date. However, other populations have shown similarly small group sizes, including Drakensberg [x ¼ 22:5, n 5 61; Henzi and Lycett, 1995], Mulu [22, Dunbar, 1992] and Bole [19, Dunbar, 1992], while recent data from Comoé, Côte d’Ivoire, also show small troop sizes [average 15 individuals, Kunz & Linsenmair, 2008]. Kwano Life-History 1 0 Mar specifically; much longer than the 29.9 months actually found. Barrett et al. [2006] found a relationship between inter-birth interval and P42t that was non-significant when Drakensberg is included (P 5 0.658), but close to significance when it is not (P 5 0.059). When Kwano is added to this dataset, this relationship is not significant, whether Drakensberg is included (r2 5 0.025, F1,9 5 0.230, P 5 0.643) or not (r2 5 0.239, F1,8 5 2.511, P 5 0.152). Kwano inter-birth intervals are longer than those at all other sites bar the outlying seasonally breeding Drakensberg population [Barrett et al., 2006; Lycett et al., 1998]. The long duration of cycling observed in Kwano troop is curious, as females apparently exhibit swellings for significant periods without conceiving, and it is unclear why females should do this when instead they could extend the period of postpartum amenorrhea and avoid the costs of exhibiting swellings. A similar phenomenon, in which females apparently exhibit swellings for long periods before conception, has been documented in, for example, hamadryas baboons [Colmenares & Gomendio, 1988], mandrills [Hadidian & Bernstein, 1979], and macaques [e.g. pig-tailed, Hadidian & Bernstein, 1979]. The function of swellings in such circumstances has often been related to infanticide avoidance; by exhibiting swellings, a female may reduce the probability of a male committing infanticide to hasten estrus. Indeed, captive hamadryas baboon females shorten the length of postpartum amenorrhea when faced with a new alpha male following a takeover [Zinner & Life-History of Wild Olive Baboons / 9 Deschner, 2000], indicating that swellings may help avert infanticide by offering incoming males mating opportunities. Similar observations have also been made in gelada, in which females exhibit swelling sooner in the presence of unfamiliar males [Dunbar, 1980]. In these scenarios it is usually assumed that cycles are ‘deceptive’ [Takahata et al., 1996], falsely advertising ovulation when the female is actually anovulatory. From observational data it is impossible to tell whether swellings are always associated with ovulation. However, hormonal analyses of Kwano troop female cycles have always detected ovulation when sampling frequency was sufficient [Higham, 2006], although we have not targeted the first swelling following postpartum amenorrhea for study, leaving open the possibility that they are anovulatory. Additionally, it is interesting to note that differences in duration of cycling between GGNP baboons and East African populations mirror patterns in chimpanzees, with West African chimpanzees having significantly longer durations of cycling before conception than East African [Deschner & Boesch, 2007]. It is also possible that long durations of cycling in some West African primates are more related to environmental factors than to social factors such as infanticide prevention. For example, we found that consumption of one specific food type, Vitex doniana, can interfere with cycling function, and prevent swelling expression [Higham et al., 2007]. Infant mortality under 12 months was high in Kwano troop, even higher than the 38% seen at Moremi, where infanticide and predation risks are severe [Cheney et al., 2004]. The occurrence of both a dominant male takeover (2003), and a wet season of exceptionally high rainfall (2004), may help to explain why recorded infant mortality was especially high during the study period. Comparison of Kwano and Gamgam Troops We found a number of significant differences between Kwano and Gamgam troops that can be linked to food enhancement. Gamgam troop had significantly shorter intervals than Kwano troop, not derived from a shorter length of postpartum amenorrhea, but rather a reduced duration of cycling. This contrasts with a study of captive olive baboons, in which inter-birth intervals were reduced by 60% compared with the wild, yet mean duration of cycling was 4.16 months, similar to that seen in the wild for many baboon populations [Garcia et al., 2006]. Interbirth intervals were instead short owing to a reduced period of postpartum amenorrhea [x ¼ 4:77 months; Garcia et al., 2006]. Infant mortality in Kwano troop was much higher than in Gamgam troop. The only death recorded in the first 12 months of life in Gamgam troop was that of a twin. Twins born on 18th August 2004 are one of the only sets of twins ever recorded in wild baboons, and the survival of both individuals was never likely [Alberts & Altmann, 2006]. Lower mortality in Gamgam troop may be related not only to the nutritional advantages of crop-raiding by this troop, but also to lower rainfall, which was, on average, 5% higher in Kwano than Gamgam. Moreover, in the year of very high rainfall (2004), which was associated with multiple infant deaths in Kwano troop, Kwano rainfall was some 570 mm (32%) higher than that of Gamgam. Kwano troop did not show evidence of birth seasonality despite highly seasonal patterns of rainfall that are both consistent in volume and reliable in timing. Seasonal birth peaks in baboon populations are often linked to rainfall and consequent patterns of food availability. For example, at Amboseli, a peak occurs in June–July [Altmann, 1980], whereas at Mchelelo, peaks are seen in September–October and January–February [Bentley-Condit & Smith, 1997]. At Moremi, although births occur throughout the year, 76% are between July and December [Cheney et al., 2004], whereas at Drakensberg, 86% occur during the rains [October–March; Lycett et al., 1999]. In the wet forests of Kwano, productivity is relatively high all year round, perhaps weakening the link between rainfall and food availability that is critical to these relationships between food availability and seasonality. If females are most likely to conceive during periods of plentiful food [as suggested by, e.g. Beehner et al., 2006; Cheney et al., 2004; Lycett et al., 1999], then seasonal cropraiding may induce seasonal breeding in Gamgam troop (Fig. 3). Testing Comparative Relationships Our data fit with some of the comparative relationships suggested by some authors, but not others. Firstly, our troop size data are within the range of group sizes suggested by Dunbar’s comparative behavior-based model [1992, 1996], but this model predicts a maximum ecologically tolerable group size of around 53—far in excess of any troops seen in the region. Dunbar’s [1992, 1996] model is based on the premise that time is a ‘‘hidden constraint’’ on baboons, and that the amount of time available to service social relationships after the necessary requirements of foraging and traveling time constrains group size. It is perhaps worth considering whether high rainfall may provide an additional constraint on available time. As the Kwano troop do not travel or forage during heavy rain, and as there are days during the wet season when heavy rain occurs for the majority of the day, this reduces substantially the amount of total time available i.e. the effective day length. A necessary consequence of this is that available time for serving social relationships is also reduced substantially, and Am. J. Primatol. 10 / Higham et al. potential to reduce available foraging time substantially, and increase the potential for disease, creates its own risk for infants that are making the transition to independence. In summary, previously published models do not always adequately predict the life-history of West African forest baboons. A combination of high rainfall and high fruit productivity in wet forests may mean that the constraints on this population are not always those assumed to be operating on baboons living in drier and more open habitats. More detailed studies of the effects of high rainfall and greater levels of frugivory on baboon life-histories will help us to understand better the environmental constraints acting on such populations. hence the maximum group sizes that can be sustained. Consideration of rainfall as a constraint on time may also help explain why predictive models of baboon distribution tend to predict that baboons should be present in areas of high rainfall where they actually are absent. Hill et al.’s [2000] regression model does not appear to predict inter-birth intervals accurately at GGNP. This could be because the climatic conditions found at GGNP are well outside the values for which the model was parameterized. More recent comparative models being developed to estimate baboon inter-birth intervals from climatic data apparently do substantially better in predicting GGNP interbirth intervals accurately (Caroline Bettridge, personal communication). Barrett et al. [2006] argued that the index of habitat productivity P42t may be positively correlated with inter-birth intervals, with longer inter-birth intervals as habitat productivity increases and seasonality decreases, owing to increasing risk for infants in the transition to independence in less seasonal habitats. Our study does not appear to provide support for this suggestion, as the addition of data from the Kwano population makes this comparative relationship nonsignificant, even in the absence of data from Drakensberg. We give two nonmutually exclusive possible explanations for this. Firstly, owing to the presence of large forests within their home range, the Kwano troop have access to relatively high plant productivity all year round, even given strong seasonality in rainfall. In more arid habitats, there is likely to be a closer link between rainfall and productivity than is found at GGNP, such that seasonality of rainfall is more important in proximately determining productivity in different months of the year. Secondly, perhaps high rainfall, with its Life-History and the Changing GGNP Environment Our data provide insight into the life-history of baboons in an environment in which they are little studied. High rainfall and closed forests found in Kwano are associated with small group sizes, long inter-birth intervals, and high infant mortality. Together, these data are consistent with a population living in an environment toward the edge of its distributional limits. Possible factors contributing to such limits include the increased disease risks associated with wet and humid closed-canopy forests, as well as competition from specialized forest primates such as guenons, mangabeys, and apes, and the reduced effective day length caused by high rainfall (see above). The detected differences in lifehistory parameters between Kwano troop and Gamgam troop are pronounced, and can be linked to environmental differences between Gamgam and Kwano troop home ranges, including lower rainfall TABLE V. Infant Survivorship Table for Kwano (K) and Gamgam (G) Troops Age interval in months x, x11 At birth 0, 1 1, 2 2, 3 3, 4 4, 5 5, 6 6, 7 7, 8 8, 9 9, 10 10, 11 11, 12 Sample size Nx Mortality rate qx Survival rate Px 5 1qx Survival from full-term pregnancy to x11 K G K G K G K G 19 18 16 14 14 12 12 12 12 11 10 10 10 16 16 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 0.05 0.11 0.13 0.00 0.14 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.08 0.09 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.06 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.95 0.89 0.87 1.00 0.86 1.00 1.00 1.00 0.92 0.91 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 0.94 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 0.95 0.84 0.74 0.74 0.68 0.68 0.68 0.68 0.63 0.53 0.53 0.53 0.53 1.00 0.94 0.94 0.94 0.94 0.94 0.94 0.94 0.94 0.94 0.94 0.94 0.94 Age interval represents month x to month x11. Sample size represents number of individuals at start of each month x. Mortality rate qx was calculated as the number of individuals who died during that interval as a proportion of the number of individuals in the sample for that interval. Survival rate is 1—the mortality rate. Am. J. Primatol. Life-History of Wild Olive Baboons / 11 in Gamgam troop range, reduced forest cover and greater predominance of savannah, and the presence of agricultural land. Although Gashaka is in the forest–savannah transition zone, much of the savannah may be derived as a result of anthropogenic impact. As such, human habitat modification at Gashaka, largely related to the removal of forests, increase in the regularity and intensity of grass burning, and the planting of crops, appears to have beneficial consequences for baboons. Environments such as those found in Gamgam troop’s range are becoming more common in the region, as in all West and central Africa. The effects of this are twofold. Firstly, the closed forests in which baboons are absent are being opened up and/or destroyed, changing habitat conditions such that they are more similar to those seen in other parts of the baboon distribution. Secondly, crops may significantly improve local food resources available to baboons. These factors together may change the environmental pressures, that currently restrict baboon distribution in West and central Africa in ways that are beneficial for baboons. This suggests that, should the clearing of forests in these regions for agricultural land continue, it may enable baboons to extend their range into regions from which they are currently excluded. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Fieldwork benefited from a permit by the Nigerian National Parks Service to the Gashaka Primate Project, which receives its core funding from the Chester Zoo Nigeria Biodiversity Programme. NCF/WWF-UK provided logistical support. Bobbo Buba, Halidu Ilyusu, Buba Bello, Nuhu Husseini, Haruna, Elodie Ey, Helen Cross, and Alejandra Pascual Garrido helped to collect data in the field. Martin Evans assisted with preparation of Figure 1, and Stuart Semple, Anthony Di Fiore, Peter Henzi, and one anonymous reviewer gave valuable comments on a previous version of the manuscript. Funding came from Roehampton University, with additional funding from The Leakey Trust, Primate Society of Great Britain, NUMICO Research B.V., British Federation of Women Graduates and the International Federation of Animal Welfare. Research complied with all applicable animal care regulations and laws, including the ethical guidelines for the treatment of animals of the American Society of Primatologists, and the UK Home Office Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. This is GPP publication number 68. References Alberts S, Altmann J. 2006. The evolutionary past and the research future: environmental variation and life history flexibility in a primate lineage. In: Swedell L, Leigh S, editors. Reproduction and fitness in baboons: behavioural, ecological, and life history perspectives. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p 277–303. Altmann J. 1980. Baboon mothers and infants. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Altmann SA. 1973. The pregnancy sign in savannah baboons. J Zoo Anim Med 4:8–12. Altmann J, Altmann SA, Hausfater G, McCuskey SA. 1977. Life history of yellow baboons: physical development, reproductive parameters and infant mortality. Primates 18:315–330. Altmann J, Altmann SA, Hausfater F. 1978. Primate infant’s effects on mother’s future reproduction. Science 201:1028–1029. Altmann J, Hausfater G, Altmann SA. 1985. Demography of Amboseli baboons, 1963–1983. Am J Primatol 8:113–125. Barrett L, Henzi SP. 2000. Are baboon infants Sir Phillip Sydney’s offspring? Ethology 106:645–658. Barrett L, Henzi P, Lycett JE. 2006. Whose life is it anyway? Maternal investment, developmental trajectories, and life history strategies in baboons. In: Swedell L, Leigh S, editors. Reproduction and fitness in baboons: behavioural, ecological, and life history perspectives. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p 199–244. Beehner JC, Onderdonk DA, Alberts SC, Altmann J. 2006. The ecology of conception and pregnancy loss in wild baboons. Behav Ecol 17:741–750. Bentley-Condit VK, Smith EO. 1997. Female reproductive parameters of Tana River yellow baboons. Int J Primatol 18:581–595. Borries C, Sommer V, Shrivastava A. 1991. Dominance, age, and reproductive success in free-ranging female Hanuman langurs (Presbytis entellus). Int J Primatol 12:231–257. Cheney DL, Seyfarth R, Fischer J, Beehner J, Bergman T, Johnson SE, Kitchen DM, Palombit RA, Rendall D, Silk JB. 2004. Factors affecting reproduction and mortality among baboons in the Okavango delta, Botswana. Int J Primatol 25:401–428. Colmenares F, Gomendio M. 1988. Changes in female reproductive condition following male take-overs in a colony of hamadryas and hybrid baboons. Folia Primatol 50: 157–174. Depew LA. 1983. Ecology and Behaviour of Baboons (Papio anubis) in the Shai Hills Game Production Reserve, Ghana. MSc Thesis. Cape Coats University, Ghana. Deschner T, Boesch C. 2007. Can the patterns of sexual swelling cycles in female Tai chimpanzees be explained by the cost-of-sexual-attraction hypothese? Int J Primatol 28:389–406. Deshmukh IK. 1984. A common relationship between precipitation and grassland peak biomass for east and southern Africa. Afr J Ecol 22:181–186. Dunbar RIM. 1980. Demographic and life history variables of a population of gelada baboon (Theropithecus gelada). J Anim Ecol 49:485–506. Dunbar RIM. 1992. Time—a hidden constraint on the behavioural ecology of baboons. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 31: 35–49. Dunbar RIM. 1996. Determinants of group size in primates: a general model. Proc Brit Acad 88:33–57. Fa JE. 1984. Structure and dynamics of the Barbary macaque population in Gibraltar. In: Fa JE, editor. The Barbary macaque—a case study in conservation. New York: Plenum Press. p 263–306. Garcia C, Lee PC, Rosetta L. 2006. Dominance and reproductive rates in captive female olive baboons, Papio anubis. Am J Phys Anthropol 131:64–72. Goodall J. 1983. Population dynamics during a 15 year period in one community of free-living chimpanzees in the Gombe National Park, Tanzania. Z Tierpsychol 61:1–60. Am. J. Primatol. 12 / Higham et al. Greenhood WF. 1971. Diets and ecology of crop-raiding baboons. MSc Thesis: University of Florida, Gainesville, FL. Hadidian J, Bernstein IS. 1979. Female reproductive cycles and birth data from an Old World monkey colony. Primates 20:429–442. Henzi SP, Lycett JE. 1995. Population structure, demography, and dynamics of mountain baboons: an interim report. Am J Primatol 35:155–163. Henzi SP, Byrne RW, Whiten A. 1992. Patterns of movement by baboons in the Drakensberg Mountains: primary responses to the environment. Int J Primatol 13:601–628. Higham JP. 2006. The Reproductive Ecology of Female Olive Baboons (Papio hamadryas anubis) at Gashaka-Gumti National Park, Nigeria. PhD Thesis. London, Roehampton University. Higham JP, Ross C, Warren Y, Heistermann M, MacLarnon AM. 2007. Reduced reproductive function in wild olive baboons (Papio hamadryas anubis) related to natural consumption of the African black plum (Vitex doniana). Horm Behav 52:384–390. Higham JP, MacLarnon AM, Ross C, Heistermann M, Semple S. 2008. Baboon sexual swellings: Information content of size and color. Horm Behav 53:452–456. Hill RA. 1999. Ecological and Demographic Determinants of Time Budgets in Baboons: Implications for Cross-Populational Models of Baboon Socioecology. PhD Thesis. Liverpool, University of Liverpool. Hill RA, Dunbar RIM. 2002. Climatic determinants of diet and foraging behaviour in baboons. Evol Anthropol 16:579–593. Hill RA, Lycett JE, Dunbar RIM. 2000. Ecological and social determinants of birth intervals in baboons. Behav Ecol 11:560–564. Kingdon J. 1997. The Kingdon field guide to African mammals. New York: Academic Press. Knapp AK, Smith MD. 2001. Variation among biomes in temporal dynamics of above ground primary production. Science 291:481–484. Knott CD. 2005. Energetic responses to food availability in the great apes: implications for hominin evolution. In: Brockman DK, van Schaik CP, editors. Seasonality in primates: studies of living and extinct human and nonhuman primates. Cambridge: CUP. p 351–378. Kunz BK, Linsenmair KE. 2008. The disregarded west: diet and behavioural ecology of olive baboons in the Ivory Coast. Folia Primatol 79:31–51. Lycett JE, Henzi P, Barrett L. 1998. Maternal investment in mountain baboons and the hypothesis of reduced care. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 42:29–56. Am. J. Primatol. Lycett JE, Weingrill T, Henzi SP. 1999. Birth patterns in the Drakensberg Mountain baboons (Papio cynocephalus ursinus). S Afr J Sci 95:354–357. Mori A, Yamaguchi N, Watanabe K, Shimizu K. 1997. Sexual maturation of female Japanese macaques under poor nutritional conditions and food-enhanced perineal swelling in the Koshima troop. Int J Primatol 18:553–579. Rogers J. 2000. Molecular genetic variation and population structure in Papio baboons 2000. In: Whitehead PF, Jolly CJ, editors. Old World monkeys. Cambridge: CUP. p 57–76. Samuels A, Altmann J. 1991. Baboons of the Amboseli basin: demographic stability and change. Int J Primatol 12:1–9. Sharman MJ. 1981. Feeding, Ranging and Social Organization of the Guinea Baboon. PhD Thesis. St Andrews, University of St. Andrews. Sigg H, Stolba A, Abegglen J-J, Dasser V. 1982. Life history of hamadryas baboons: physical development, infant mortality, reproductive parameters and family relationships. Primates 23:473–487. Smuts B, Nicolson N. 1989. Reproduction in wild female olive baboons. Am J Primatol 19:229–246. Sommer V, Adanu J, Faucher I, Fowler A. 2004. Nigerian chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes vellerosus) at Gashaka: two years of habituation efforts. Folia Primatol 75:295–316. Strum S. 1991. Weight and age in olive baboons. Am J Primatol 25:219–237. Strum SC, Western JD. 1982. Variations in fecundity with age and environment in olive baboons (Papio anubis). Am J Primatol 3:61–76. Takahata Y, Ihobe H, Idani G. 1996. Comparing copulations of chimpanzees and bonobos: do females exhibit proceptivity or receptivity? In: McGrew WC, Marchant LF, Nishida T, editors. Great Ape Societies. Cambridge: CUP. p 146–155. Tappen NC. 1960. Problems of distribution and adaptation of the African monkeys. Curr Anthropol 1:91–120. Warren Y. 2003. Olive Baboons (Papio cynocephalus anubis): Behaviour, Ecology and Human Conflict in Gashaka-Gumti National Park, Nigeria. PhD Thesis. London, University of Surrey Roehampton. Warren Y, Buba B, Ross C. 2007. Patterns of crop-raiding by wild and domestic animals near Gashaka Gumti National Park Nigeria. Int J Pest Manage 53:207–216. Williamson DK, Dunbar R. 1999. Energetics, time budgets and group size. In: Lee PC, editor. Comparative Primate Socioecology. Cambridge: CUP. p 320–338. Zinner D, Deschner T. 2000. Sexual swellings in female hamadryas baboons after male take-overs: ‘‘Deceptive’’ swellings as a possible female counter-strategy against infanticide. Am J Primatol 52:157–168.