Depression in Adolescence Anne C. Petersen, Bruce E. Compas, Jeanne Brooks-Gunn,

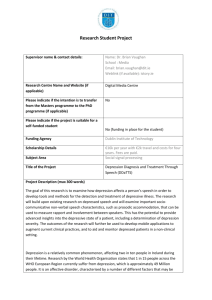

advertisement