Importers, Exporters and Multinationals: A Portrait of Firms in

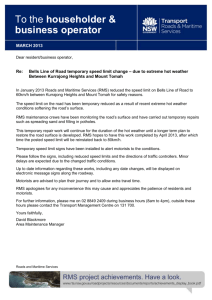

advertisement