Document 12093490

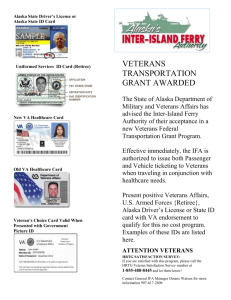

advertisement