HISTORIC STRUCTURES PRESERVATION MANUAL

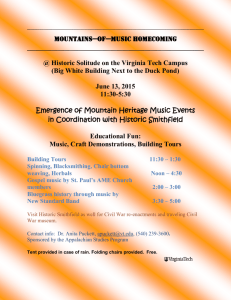

advertisement