FROM THE EDITORS CLIMATE CHANGE AND MANAGEMENT

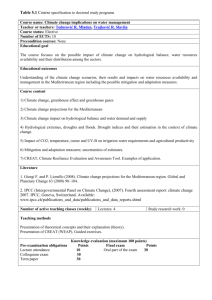

advertisement

娀 Academy of Management Journal 2014, Vol. 57, No. 3, 615–623. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.4003 FROM THE EDITORS CLIMATE CHANGE AND MANAGEMENT passed, leading to much larger climate changes and impacts. How can changes of such magnitude not be important for a wide range of organizations in the private, public, and non-profit sectors? Perhaps it is just the mismatch between the timescales of business and that of the climate that has made it difficult to grasp what climate change means for organizations in the future. Or, perhaps it is the uncertainty that surrounds any projections of our future climate—an uncertainty arising from the complexity of the climate system itself, as well as from our social, political, and economic choices. Climate change is so pervasive that its causes and consequences show up at every level of analysis of interest to organizational scholars. This can be taken as an opportunity, as it enables scholars to consider the topic at every scale—from how individuals evaluate their environmental issue advocacy (Sonenshein, DeCelles, & Dutton, 2014), to how the staging of international climate conferences shapes (in)action on the issue over time (Schüßler, Rüling, & Wittneben, 2014). As climate impacts become more apparent over the next few decades, they will impinge on the structure and functioning of our value chains and industries, the resilience of organizations, individual work patterns and practices, and the social orders and broader governance systems upon which organizations rely. In other words, climate change and responses to it will fundamentally reshape many of the phenomena, interactions, and relationships that are of central concern to management scholars. In this editorial, we offer a brief primer on the science and implications of climate change, before exploring some avenues for research and engagement on these essential issues. Editor’s note: This editorial is part of a series written by editors and co-authored with a senior executive, thought leader, or scholar from a different field, to explore new content areas and grand challenges with the goal of expanding the scope, interestingness, and relevance of the work presented in the Academy of Management Journal. The principle is to use the editorial notes as “stage setters” to open up fresh, new areas of inquiry for management research. GG Climate change is one of the greatest challenges we confront in the 21st century. On current trends, by the end of the century, the warming effect of our greenhouse gas emissions will have taken us far away from pre-industrial climatic conditions. In fact, our climate will be as different from pre-industrial conditions as it was when the Earth emerged from the last ice age some 20,000 years ago. In other words, just over 200 years of human and industrial activity will have wrought fundamental change to our climate system. The rise of organizations and industrialized production has set us on this path, yet organizations are equally critical to mitigating and adapting to climate change. Understanding the science and policy of climate change, and the ways in which the associated issues are shaped by and shape the subjects of our attention, is therefore of great importance to management scholars. Climate change is already manifest in changes to growing seasons, water resources, ocean acidification, and coastal flooding. The Earth’s global mean surface temperature has risen by 0.85°C since the late 19th century, and is as likely as not to exceed a 4°C rise, relative to the period 1850 –1900, by the century’s end. The corresponding rise in temperature over tropical continents would be larger, and the warming over northern, high-latitude continents some two to three times greater (IPCC, 2013). Such changes would have far-reaching—though, as yet, still only partially understood— effects on atmospheric circulation, precipitation levels, and extreme weather, impacting just about every aspect of our lives. It is possible that thresholds (“tipping points”) in the climate system, such as the release of methane from melting permafrost, will be A GLIMPSE INTO THE SCIENCE OF CLIMATE CHANGE In its 4.5 billion-year history, the Earth has gone through dramatic changes, with periods when the poles were ice-free and others when ice sheets reached the tropics (Pierrehumbert, 2010). Even in 615 Copyright of the Academy of Management, all rights reserved. Contents may not be copied, emailed, posted to a listserv, or otherwise transmitted without the copyright holder’s express written permission. Users may print, download, or email articles for individual use only. 616 Academy of Management Journal June FIGURE 1 Variations of Deuterium (␦D) in Antarctic Ice, a Proxy for Local Temperature, and the Atmospheric Concentrations of the greenhouse gases, carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and Nitrous Oxide (N2O) in Air Trapped within the Ice Cores and from Recent Atmospheric Measurements. Data Cover 650,000 Years; Shaded Vertical Bands Indicate Current and Previous Interglacial Warm Periods. (Adapted from Figure 6.3, IPCC, 2007.) the Ice Age of the past million years, there have been changes over a hundred thousand years from interglacial to glacial periods in which the ice sheets advanced over North America and northwest Europe, and back again to an interglacial period as at present. However, human societies have evolved in the last 10,000 years in an unusually stable climate. Certainly there has been variability, particularly on a regional scale, but, at the global scale, we have developed—indeed, thrived— during a temporal island of climatic stability. The Earth’s climate depends fundamentally on the difference between the amount of solar energy flowing into the Earth minus the amount of energy leaving in the form of infrared radiation. In equilibrium, the infrared (heat) radiation emitted from the Earth exactly balances the absorbed solar energy. If there were no atmosphere, this would happen when the Earth’s surface was at an average temperature of ⫺18°C, assuming that the same proportion of solar radiation is reflected. Fortunately, the water vapor and other greenhouse gases within the atmosphere trap some infrared radiation emitted from the Earth’s surface, warming the atmosphere until a new energy balance is achieved. The analogy of a “greenhouse” is used to label this effect. The natural greenhouse effect increases the Earth’s surface temperature by some 33°C, making the planet habitable. The atmospheric concentration of major greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane has changed, and continues to change over time, with a strong effect on the Earth’s energy balance. These changes have been due both to natural processes and, more recently and dramatically, the explosion in human activity. The burning of fossil fuels and changes in land use contribute particularly, but not exclusively,1 to increases in concentrations of carbon dioxide and methane to levels unseen in at least the last 1 The “Summary for Policy Makers” produced by Working Group I as part of the Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change gives more details (IPCC, 2013). 2014 Howard-Grenville, Buckle, Hoskins, and George 800,000 years (see Figure 1, which indicates the sharp upturn in greenhouse gas concentrations on the righthand side). Increased levels of atmospheric greenhouse gases enhance the trapping of the infrared radiation emitted by the Earth and therefore produce extra warming, with the rate of warming determined by the absorption of heat by the oceans. While the effects of natural climate variability will still play a major role in our weather over the next few decades, the trend from human-induced climate change will increasingly assert itself through the century and take us into climatically uncharted territory. As a recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report warned, the increasing magnitudes of warming exacerbate the likelihood of severe, pervasive, and irreversible impacts (IPCC, 2014a). Whereas the science of climate change reflects longer time horizons, the effects of climate change are already being felt. Most reported impacts so far are due to warming and/or changes in precipitation patterns, with emerging evidence of the impacts of ocean acidification. We are seeing change in species’ ranges and seasonal activities and changes to hydrological systems, affecting water resources and quality. Negative impacts of climate change on crop yields have been more common than positive impacts. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO, 2014) reports that 13 of the 14 warmest years on record have all occurred in the 21st century (the exception is the strong El Nino year, 1998). The European “mega heat waves” in 2003 and 2010 caused thousands of deaths and large-scale crop losses (Barriopedro, Fischer, Luterbacher, Trigo, & García-Herrera, 2011). Such events are expected to become more frequent, while the increasing intensity of rainfall and rising sea levels will heighten risks from flooding. THE POLICY OF CLIMATE CHANGE Current efforts to limit the risks of climate change take place under the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and its associated Kyoto Protocol. In addition to the usual problems of collective action and free-riders that make effective international climate action difficult, the UNFCCC also built in a sharp distinction between the responsibilities and roles of developed and developing countries,2 which now has to be reinter- 2 The UNFCCC emphasized “common but differentiated responsibilities,” whereby developed economies were to take the lead in combating climate change. 617 preted in the light of the subsequent transformation of the global economy. The Copenhagen Accord in 2009 was a breakthrough in this regard, with developing economies (e.g., China and India) making national commitments to reduce their emissions intensity (not, as yet, their absolute emissions) in the period up to 2020 alongside pledges to reduce the level of emissions in major developed economies, including the United States. For the period beyond 2020, governments agreed, at the 2011 Durban climate summit, to draw up the blueprint for a fresh, universal agreement “with legal force” that should be agreed at the Paris summit in 2015. However, progress has so far been slow and political traction limited. Whatever finally emerges will be firmly rooted in the post-Copenhagen world, where national emission-reduction pledges beyond 2020 are carefully calibrated on those offered by others. Whether this will deliver the scale of emissions reductions required by the policy targets currently under discussion remains to be seen. There is already widespread action at a national and sub-national level, albeit at an early stage in many countries. In 2012, 67% of global greenhouse gas emissions were subject to national legislation or strategies, compared to 45% in 2007 (IPCC, 2014b). Potentially the world’s largest carbon market, China, launched seven pilot emissions trading schemes at a provincial and municipal level in 2013. The United Kingdom has in place a comprehensive framework of legally binding, rolling carbon budgets to meet its commitment in law to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 80% in 2050 from 1990 levels. In contrast, a number of countries face significant domestic political constraints. For example, the U.S. President’s climate change action plan—to deliver a 17% emissions reduction by 2020 on 2005 levels— has to be delivered through existing regulatory powers, following the failure of efforts to establish a federal emissions trading scheme. In the European Union, a combination of structural economic problems and concerns over the competitiveness of energy-intensive business and energy costs for household consumers has raised questions about whether it is willing to continue taking a lead on tackling climate change. In the absence of determined, international mitigation action, new leaders and initiatives have emerged, and no doubt will continue to do so in response to increasing risks and new opportunities. For example, members of the C40 group of global megacities are already acting locally and collabora- 618 Academy of Management Journal tively. Global firms such as Unilever are taking a visible role in addressing a range of sustainability issues, including climate change. Instead of single carbon price guiding actions, organizations are now facing an increasingly complex operating environment, with hard-to-understand implications for their future strategy, location, and profitability. The sheer proliferation of initiatives at different geographic, societal, and governmental levels with varying regulatory frameworks is one of the pressures leading some organizations to push for comprehensive national- and regional-level climate policy. The policy uncertainty may, in many cases, be of greater concern than uncertainties over future climate projections. IMPLICATIONS FOR ORGANIZATIONS AND MANAGEMENT So, what should we do? We need to adapt to the changes already in train by building in resilience to all aspects of economic and social activity, and by learning how to cope with unprecedented levels of uncertainty and a rapid pace of change. We also need urgently to find a way to limit the risks through substantial and sustained mitigation action that will reduce emissions radically— by 35–75% globally by 2050 from 1990 levels—if we are to limit warming to the 2°C target that is the current focus of international negotiations. Private, public, and not-for-profit organizations will need to engage a suite of approaches under the broad banners of adaptation and mitigation to cope with the implications of climate change. We highlight four broad implications of climate change to illustrate how this issue poses pressing and important questions for management and organizational scholars. These are neither exhaustive nor exclusive, but are meant to illustrate a wide range of questions ripe for study, across the typical levels of analysis and within the range of methodologies that management scholars employ. First, climate change will reshape value chains, including supply networks, production arrangements, and the provision of energy and water. Management scholars can study how governance, coordination, and risk-mitigation arrangements can anticipate and respond. Second, while it is almost a cliché to speak of the unprecedented change today’s organizations face, the types of change to which they must respond due to climate change are truly without precedent. Such changes demand new approaches to decision making, forecasting/ June planning, and organizational adaptation. Third, climate change will alter how we live and work. Cities will need to become far more resource efficient, and individual patterns of mobility will no doubt shift. For organizational scholars, these changes prompt a rethink of how managers and employees interact, motivate, and engage one another, and identify with their employing organizations. Finally, climate change will have far-reaching impacts on fragile human populations, while forcing difficult choices upon affluent societies. Governments will face the challenges of mustering citizen support for fundamental changes in energy, transportation, and infrastructure, regulating large-scale carbon sequestration projects, and, perhaps, managing climate migrants. Organizational scholars can study how business, society, and public entities mobilize for and navigate these challenges. Reshaping Value Chains Part of any response to climate change will involve a shift in the mix of energy sources that underpin our economy. Fossil fuels— currently around 80% of global primary energy demand— will increasingly be replaced by low-carbon sources. According to the IPCC, renewable energy accounted for just over half of the new electricity generating capacity added globally in 2012, led by growth in wind, hydro, and solar power. Such shifts might also be accompanied by a more distributed network of energy production and consumption. For example, stand-alone renewable systems can make a significant difference to the lives of the 1.3 billion people without access to electricity in developing economies (IPCC, 2014b), particularly where it is uneconomic or difficult to build centralized grid systems. Regardless of the mix of energy sources, we will need to become far more efficient in our energy consumption. The transportation of products, components, raw materials, and people is a major consumer of energy, accounting for about one-quarter of total energy consumption in a developed country. Furthermore, transportation disproportionately relies on fossil fuels, as opposed to other sources of primary energy. This, and the coming changes in land use and agricultural productivity precipitated by climate change, has already led some companies to fundamentally rethink their supply chain, its scale and extent, and their relationships with primary producers. For example, the U.K. retailer Sainsbury’s has made a series of “20⫻20” sustainability commitments covering en- 2014 Howard-Grenville, Buckle, Hoskins, and George vironmental performance of suppliers as well as reducing the company’s absolute operational emissions of greenhouse gases by 30% by 2020 relative to 2005. As organizations work to improve their energy efficiency and reduce their carbon footprint, largescale changes are likely in the geography and functioning of production systems. Rather than moving raw materials and finished goods long distances, companies may seek to produce closer to the point of consumption, for example. The currently popular move towards locally grown foods is only one early manifestation of what could become more widespread. Technologies such as 3D printing are making possible the production of quite sophisticated goods and components in customizable, small batches, close to the points of consumption or assembly. For example, aircraft manufacturers Airbus and Boeing are using it to improve the performance of their aircraft and reduce maintenance and fuel costs. And, companies can exploit the “waste” or by-product of others’ processes, or use the recovery of end-of-life products, to replace virgin raw materials in the production of goods. “Industrial symbiosis” and related concepts such as the “circular economy” encourage organizations to recover and reuse energy, water, and materials, mimicking natural ecosystems. The longest-lived industrial symbiosis is found in Kalundborg, Denmark, where exchanges of excess heat, steam, and material resources have occurred between organizations since the early 1970s. Organizational scholars can study how such shifts in organizational supply networks alter interorganizational relationships, contracting, and risk-mitigation approaches. For example, how might the sourcing of “waste” material as an input alter traditional supply arrangements? Will boundaries of the firm, the nature of the firm’s “industry” affiliations, and even organizational identities shift? How will localized provision of services often provided at scale by public entities (energy, water) shift the balance of power in interorganizational relationships, and how will firms be forced to respond if they can no longer expect high-quality, highly reliable, centralized provision of such resources? Will organizations adopt new models of engagement with suppliers to cope with shifts in supply conditions? Scholars need not think of climate change-induced shifts as impacting only those organizations that produce or are heavy users of energy. Indeed, part of the response to the need for radical efficiency increases may be new markets for services. 619 The market for certain goods— cars, for example— may be supplanted by a market for services (mobility) in which new market actors (car-sharing companies, not automobile manufacturers and retailers) will dominate. To what extent will such changes precipitate new organizational forms, or new types of networks and alliances (e.g., between car-sharing services and providers of electricity)? How will such changes show up in the ways that firms interact with consumers and portray the value of their services? How will information technologies enter into and become central to the provision of such services? Organizational Resilience and Adaptation With climate change comes much more than shifts in energy production and consumption: it will require fundamental changes to how we use the land and water in many regions. Some organizational responses are already discernable. For example, Coca-Cola has committed to “water neutrality” at the local level across its globally distributed production facilities, aiming by 2020 to return to communities or nature the amount of water used in product and production. Cities with considerable populations near sea level are bolstering their defenses against extreme weather—for example, New York City’s Public Service Commission is requiring the electric utility serving the city to upgrade to the tune of $1 billion to prevent damage from future flooding. Many responses to climate change will be much more difficult to manage, because the information available to organizations may well not support the kinds of decisions, made on the appropriate time frames, for prudent action. Specific impacts, in specific times and places, will be hard to predict. High uncertainty in outcomes will drive high volatility in operating conditions, challenging current approaches for managing risk and making decisions. Ways of organizing that foreground resilience and responsiveness (Whiteman & Cooper, 2000, 2011), rather than scale or growth, will gain further attention. Organizational scholars have only infrequently probed the nature of organizational resilience, sometimes in the face of extreme events, but more by looking at high-reliability organizations. There is opportunity to develop theory on what adaptation and resilience looks like under the assumption of significant disruption to “business as usual.” Because the climate is a non-linear system and its specific influences 620 Academy of Management Journal at a given time and place are largely unpredictable, proactive adaptability, as opposed to punctuated reactive change, may become a “new normal” for organizations. The limited predictive capabilities that are developed for climate change will have to be used with understanding of their (at best) probabilistic nature. A second area where climate change will usher in significant change at the organizational level is in the development of technologies. A fundamental alteration in energy provision infrastructure, while not unprecedented in our history—which has seen the development of mass electrification, the rise of the automobile, and, most recently, the near-ubiquitous use of information technology—nonetheless shifts the playing field for existing and emerging organizations. Opportunities for entrepreneurship abound, evidenced in the staggering rise of “clean tech” companies and funding in recent years (clean technologies investment worldwide topped $8 billion in 2008, up by a factor of ten from only six years earlier). Equally important are opportunities for social entrepreneurship to address the challenges faced by the world’s vulnerable societies while seeking environmentally favorable solutions for the provision of clean water, clean energy, communications, and mobility infrastructure. One example is TERI’s “Lighting a Billion Lives” initiative that aims to provide poor Indian households with solar lanterns, each of which in its life of 10 years should replace about 500 – 600 liters of kerosene, mitigating about 1.5 tons of CO2 emissions. The scheme is operated and managed by a local entrepreneur trained under the initiative who rents the solar lamps at an affordable rate to households in un-electrified or poorly electrified villages. Organizational scholars can rethink our understanding of innovation and technology development and diffusion. Do new constraints posed by climate change alter current models? How do we anticipate and manage the uncertainty posed for organizations as a result of large-scale change in both the conditions in which organizations must operate and the underlying technologies available? Will new forms of partnership arise out of the need to simultaneously dismantle existing infrastructure while building new elements? How will public entities, private organizations, and the not-for-profit sector develop collaborations to address the social, economic, and environmental needs that arise through this transition? June Shifts in Work and Life Climate change, coupled with increasing urbanization, will demand that cities become more resource efficient, which might fundamentally alter where, and, to some degree, how, individuals live, work, and move about. Just as telecommuting was a response to traffic congestion and work–life balance concerns of the 1990s, so will responses to climate change likely prompt related shifts in how work is distributed, how employees interact with one another, and how physical assets are used by organizations. The efficient use of energy and other resources may lead to decentralization and de-synchronization of activity (e.g., encouraging employees to work remotely, avoiding transportation, or to work at “off-peak” hours). At the same time, production of some goods currently shipped long distances may become localized around population centers, leading to a modified distribution of economic activity. Employees might find their skills exercised in new patterns of time and space, and may also find that new skills are in demand—from “hard” skills to develop technologies and infrastructures to “soft” skills that enable them to communicate and collaborate under new circumstances, akin to but undoubtedly altered from those required in the digital age. These issues are often described as relevant only to developed economy employees. However, the vast number of people who live and work in developing nations, where, increasingly, pressures will be placed on development using clean energy technologies and greater resource efficiency may require a radical rethink of employment practices, human resource management, coordination of distributed work, and location choices for businesses. Shifts in organizational choices for production and consumption are likely to have debilitating effects on relatively unskilled workforces across the world. Many trends such as economic growth, urbanization, and demographic transitions in developing countries will have significant effects on the nature and distribution of employment, but changes in response to climate change may well exacerbate some of these. Organizational scholars are already beginning to explore how employees value their organization’s sustainability commitments that broadly address both environmental and social needs. Forwardlooking organizations may find they are able to attract, retain, and motivate employees by making their commitments to “doing good” deeper and 2014 Howard-Grenville, Buckle, Hoskins, and George more transparent. As climate change is a ubiquitous issue, touching all employees in their personal lives (e.g., through rising food prices, due to crop disruptions, or opportunities to alter transportation modes), organizations may find considerable resonance and engagement from their employees in support of efforts to address climate change. Organizational scholars might explore whether motivation, commitment, identification, or pro-social behaviors are differently manifested when issues such as climate change are confronted by an organization. Other questions ripe for study include how organizational responses to climate change shape employee and managerial behavior. Do altered patterns of mobility, co-presence, and communication change collaboration, creativity, or productivity? How do managers lead and motivate employees under altered conditions? In the developing world, how might climate change alter work conditions and worker mobility? Will the inevitable impacts of climate change on health and disease become a significant factor in how organizations structure their relationships with employees, and the types of benefits they are called on to provide? Societal Shifts At the societal level, climate change will usher in infrastructure changes that anticipate and respond to changing conditions, as well as less predictable exposures to extreme events. Each of these will place burdens on society to adapt and respond. In the case of infrastructure changes, giving members of the public voice and addressing community concerns is already regarded as important— but likely underutilized—for developments such as onshore wind turbines. Even more challenging questions will be posed in decades to come. For example, what are appropriate measures and locations for geological carbon sequestration, the injection of CO2 deep into the ground? How should we balance the demand for land, water, and other resources to grow crops for fuel versus food? How can we use “big data” and new communication technologies to inform, encourage participatory approaches to, and manage large-scale adaptation? How should the ownership and governance of such data be structured to best to deliver social and not just private 621 value? How do we weigh and allocate responsibility for effects felt far from their sources?3 Extreme events pose further challenges for societies. How should the industrialized world assist expected “climate migrants” displaced from their homes and livelihoods by rising sea levels, persistent drought, or devastating storms? Low-lying Bangladesh, home to more than 155 million people, is already vulnerable to the effects of increased intensity of flood, cyclone, and storm surge, and salinity intrusion. How much worse will the situation be in 2050? Although extreme weather events and climatic shifts will not discriminate between richer and poorer nations, those worse off will, in many cases, be the most vulnerable and least able to adapt. This will create challenges for mobilizing, organizing, and coordinating large-scale change. There challenges also hold opportunity to fundamentally rethink risk frameworks and how private and public entities work to manage and mitigate risk. Organizational scholars have long studied the nature of social change, whether triggered by social movements, technologies, or shifts in societal values. Climate change, with its global yet highly disperse and varied impacts, offers opportunity to extend this work. What new models of social mobilization and change might be occasioned by efforts to respond to or mitigate climate change? How might civil society and public and private organizations build resilient communities and economies? To what degree does a response to climate change demand shifts in cultural or institutional values or logics, and how will these emerge and evolve? What role do organizations play in ushering in such changes? CLOSING THOUGHTS While the intent of this editorial is to offer some insight into the science and policy of climate change, and outline potential implications for organizations and organizational scholars, it is important to recognize that our scholarly community is already grappling with a number of these questions. Recent journals’ special issues focus explic- 3 For example, a recent study shows that between 12% and 25% of sulfate pollution in the western United States originates from production in China for export (Lin et al., 2014). To an even greater extent, greenhouse gases do not respect national boundaries. 622 Academy of Management Journal itly on climate change and organizations, and the topic has increasingly moved from the fringe to the mainstream, including the pages of AMJ, over the past decade and a half. When the IPCC concludes with high evidence and agreement that “deep cuts in emissions will require a diverse portfolio of policies, institutions, and technologies as well as changes in human behavior and consumption patterns” (IPCC, 2014c: 4), this offers an opening for organizational scholars of all interests, and theoretical and methodological specialties, to engage with this pressing issue. We hope this editorial provides some inspiration on how we might use our expertise to better understand the challenges climate change poses to organizations, individuals, and societies, and we look forward to welcoming such work in our editorial process. Jennifer Howard-Grenville Lundquist College of Business University of Oregon June IPCC. 2014a. Summary for policymakers. In Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (final draft report). Cambridge, England, and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Available at https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/ wg3/. IPCC. 2014b. Summary for policymakers. In Climate change 2014: Mitigation of climate change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, England, and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Available at https:// www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg3/. IPCC. 2014c. Chapter 1: Introductory chapter. In Climate change 2014: Mitigation of climate change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, England, and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Available at https:// www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg3/. Simon J. Buckle Grantham Institute for Climate Change Imperial College London Lin, J., Pan, D., Davis, S. J., Zhang, Q., He, K., Wang, C., et al. 2014. China’s international trade and air pollution in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111: 1736 –1741. Brian J. Hoskins Grantham Institute for Climate Change Imperial College London Pierrehumbert, R. T. 2010. Principles of planetary climate. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Gerard George Imperial College Business School Imperial College London Schüßler, E., Rüling, C., & Wittneben, B. 2014. On melting summits: The limitations of field-configuring events as catalysts of change in transnational climate policy. Academy of Management Journal, 57: 140 – 171. REFERENCES Barriopedro, D., Fischer, E. M., Luterbacher, J., Trigo, R. M., & García-Herrera, R. 2011. The hot summer of 2010: Redrawing the temperature record map of Europe. Science (New York, N.Y.), 332: 220 –224. IPCC. 2007. Technical summary. In Climate change 2007: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [S. Solomon, D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K. B. Averyt, et al. (Eds.)]. Cambridge, England, and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. IPCC. 2013. Summary for policymakers. In Climate change 2013: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S. K. Allen, J. Boschung, et al. (Eds.)]. Cambridge, England, and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Sonenshein, S., DeCelles, K., & Dutton, J. 2014. It’s not easy being green: The role of self-evaluations in explaining support of environmental issues. Academy of Management Journal, 57: 7–37. Whiteman, G., & Cooper, W. H. 2000. Ecological embeddedness. Academy of Management Journal, 43: 1265–1282. Whiteman, G., & Cooper, W. H. 2011. Ecological sensemaking. Academy of Management Journal, 54: 889 –911. World Meteorological Organization. 2014. WMO statement on the status of the global climate in 2013. Available at http://library.wmo.int/opac/index. php?lvl⫽notice_display&id⫽15957. Jennifer Howard-Grenville is associate professor of management at the University of Oregon’s Lundquist College of 2014 Howard-Grenville, Buckle, Hoskins, and George Business. She is an associate editor of the Academy of Management Journal, covering the topics of sustainability, corporate social responsibility, institutional theory, organizational identity, organizational adaptation, and social change. Simon Buckle is the Policy Director at the Grantham Institute at Imperial College London. He was Pro-Rector for International Affairs at Imperial (2011–13) and formerly was a senior British diplomat. He has a doctorate in theoretical physics, was appointed a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in 2007, and is a Fellow of the Institute of Physics. Sir Brian Hoskins is the chair of the Grantham Institute for Climate Change at Imperial College London, and holds a joint appointment with University of Reading, where he is professor of meteorology. His international roles have included being vice-chair of the Joint Scientific Committee for the World Climate Research Program, 623 president of the International Association of Meteorology and Atmospheric Sciences, and involvement in the 2007 IPCC international climate change assessment. He played a major part in the 2000 Report by The Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution and is currently a member of the UK Committee on Climate Change. He is a member of the science academies of the United Kingdom, USA, China, and Europe and has received a number of awards, including the top prizes of the U.K. and U.S. meteorological societies. He was knighted in 2007 for his services to the environment. Gerry George is professor of innovation and entrepreneurship at Imperial College London and serves as deputy dean of the business school. He is also the editor of the Academy of Management Journal.