Thinking Developmentally: The Bible, the First-Year College Student, and Diversity

advertisement

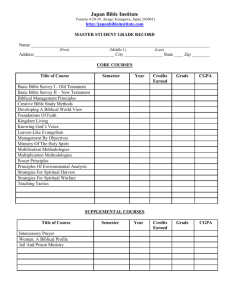

Teaching Theology and Religion, ISSN 1368-4868, 2004, vol. 7 no. 4, pp 223–229. Thinking Developmentally: The Bible, the First-Year College Student, and Diversity Elna K. Solvang Concordia College, Moorhead, Minnesota Abstract. The Bible is a non-western text subject to a variety of interpretations and applications – constructive and destructive. The academic study of the Bible, therefore, requires critical thinking skills and the ability to engage with diversity. The reality is that most firstyear college students have not yet developed these skills. Rather than bemoan students’ lack of development, the essay explores ways of teaching and applying critical thinking within the context of an introductory Religion course. The essay claims that first-year college students can better learn the content of the discipline and function in a pluralistic world if the teaching of critical thinking skills is a part of the pedagogy. As a teacher of Bible – Hebrew Bible and the New Testament – I must help contemporary mid-western college students negotiate an ancient non-western text. Moreover, this encounter with an ancient text is supposed to assist them in being “thoughtful and informed men and women” who, according to our college’s mission statement, will “influence the affairs of the world.” Responsible engagement in that world demands appreciation for its complex diversity. As a teacher in the academic setting, I do not assume that all my students embrace the Bible as sacred scripture, nor do I presume to convince them to hold that position. Yet I believe that reflection on the perspectives, values, and traditions of this ancient – other – world can assist students in reflecting on the values and practices of their own. Therefore, a goal of mine is to produce students capable of informed and articulate reflection on the content of the Bible, who can use their study of the biblical texts as a point for meaningful reflection on their participation in a pluralistic world. The Connection between Critical Thinking and Diversity Both the academic study of the Bible and engagement in a pluralistic world require (a) critical thinking skills and (b) the ability to understand and value perspectives other than one’s own. The reality, however, is that firstyear college students typically have not developed these skills. This reality came home to me in a dramatic way about a year ago. Imagine 450 first-year students, scattered across a large gym, sitting on the floor in small groups. These students had just completed a unit on diversity and participated in anti-racism training. In this small group exercise they were to discuss where they would place their college on a continuum that ranged from an exclusive-racist organization, to an acceptinginclusive institution, to a multicultural and anti-racist institution. I was stunned and grieved by the level of resentment to the training and resistance to considering how personal behavior and institutional practices might be perceived by others as exclusive or racist. Afterwards I kept puzzling over what we as faculty and staff were doing wrong. How could we have failed to convince students of the present reality of racism regardless of the goodness of their intentions? What could I point to in my own courses on the Bible that would help them see how diversity and human community are linked? How could we help them see that they were privileged because of the color of their skin, whether or not they felt they were superior? That what their community neighbors wanted was not tolerance but dignity and justice? As I stewed over their stubbornness I was keenly aware of my own. The picture that flashed through my head was that of a donkey sitting down refusing to budge as someone was desperately tugging on the other end of the rope. Something’s wrong with this picture, I © Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2004 Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA 224 Solvang thought. What can we do to change it? Then it occurred to me that this picture of the donkey and the one pulling focused on the will to change. I began to ask myself, how are we helping students develop the skill to change? I reflected on this question with two sympathetic colleagues in the English Department. We looked at some of the research on the emotional and intellectual development of college students, particularly Perry’s study of “structural changes in . . . assumptions about the origins of knowledge and value” (Perry 1999, 229) and Chickering’s theory of psychosocial development in adolescence and early adulthood (Chickering and Reisser 1993). These helped us interpret responses to diversity in the workshop and in the classroom with appreciation for where first-year students are developmentally. Based on the research and our own classroom experiences we prepared a short list of general characteristics of incoming college students: • they tend to be dualistic thinkers • they tend to be focused on self and have difficulty thinking outside their own experiences and circumstances • they tend to have little skill and experience with critical thinking • they tend to be more emotive than reflective • their communication skills tend to be more suitable for private than public contexts and for personal narrative than persuasive argument The list is nothing new or surprising; it reflects the familiar gap between the way incoming college students think and approach learning and the levels of critical thinking and communication that faculty expect. What is new – for my colleagues and me – is our decision to make the teaching of critical thinking part of our pedagogy in our respective course discipline areas. This involves helping students acquire the cognitive skills that go into arriving at judgments based on accurate and relevant information that take into account multiple perspectives and acknowledge assumptions, inferences, implications, and consequences. Some colleges have first-year seminar classes that are designed to help students acquire critical thinking and communication skills. My college does not have such a program. The first-year course that we do have – Principia, which is intended as an introduction to liberal learning – is taken by half of the incoming students in their second semester of college. Therefore, whether it is in the writing classes my English department colleagues teach or in the introductory Religion course I teach, we each face the task of changing the learning profile of first-year students by aiding them in developing new thinking, learning, and expressive skills. While some faculty might consider the teaching of critical thinking a remedial strategy, we view it as appropriate to the developmental stage of incoming college students and crucial for student engagement with the subjects we are passionate about and hired to teach. Students need critical thinking skills as they encounter the diversity inherent in the content of the subjects we teach. The Bible must be recognized as originating in a time and a culture other than one’s own. The Bible cannot be studied without giving attention to its use throughout history in shaping social structures, cultural norms, national identities and international policies, and examining the assumptions and consequences of such use. The academic study of the Bible involves conscious reflection on the subjective position from which one reads, as well as the ability to recognize the perspectives of other interpreters. The challenge is not only to teach first-year students about the diversity that exists, but for them to acquire the skills to engage diversity productively. The teaching of critical thinking skills can assist first-year students to learn the content of our disciplines and function in a pluralistic world. Critical Thinking and the Bible The religion course that first-year students at my campus enroll in is titled “Christianity and Religious Diversity.” It is a required course intended “to introduce students to the academic study of religion through the study of Christianity’s classic texts and contemporary expressions.” Students are also introduced to four ways in which religions and religious phenomena can be studied, namely, interpretive, historical, comparative, and constructive methodologies. Each of these methods is developed more fully in the upper-level course offerings in the department. The interpretive area focuses primarily on the study of scripture and biblical languages. Church history, including the development of particular denominations and expressions of the Christian tradition, is the focus of the historical area. The comparative area focuses on relating and differentiating religions. The constructive area focuses on ethics and examining ways God is perceived to be present and active in the world today. One of the objectives of the course is to “encourage critical inquiry and constructive thought about religion and religious questions,” however the teaching of critical thinking skills is not specifically stated. Since there are 10–12 faculty teaching this course each semester, we have agreed to a common set of objectives, the same number of tests, the same total number of pages for writing assignments and to include readings from particular parts of the biblical canon and primary texts from particular periods in church history. Each instructor has the freedom to design their class to meet the common objectives as well as to reflect their passions and expertise. My sections, therefore, concen© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2004 225 Thinking Developmentally trate more on reading, interpreting, and the ethics of contemporary applications of biblical texts. Though I cover all four approaches for studying religion in the course, in this essay I focus on the interpretive methodology. The expectations for the material to be covered and the confines of the semester schedule may make it appear foolish to talk about adding the teaching of critical thinking to a discipline-specific course. Yet, the limits of time are a reminder that (1) what we teach in the semester should equip students to continue their learning and exploration of these issues in the future; and (2) it is to our advantage to maximize the learning process in the limited time we do have with students. I would argue that I do not take time away from covering content in the way I teach critical thinking skills. It is the content of the course that provides the occasion to teach those skills, and those skills are necessary for wrestling with the content of the course. One of the tools I use to teach critical thinking is “Bloom’s Taxonomy.” I introduce it to my students on the second day of class. Bloom’s Taxonomy displays a range of what it means to “know” something – from being able to repeat information, to being able to apply information, to being able to analyze information, to being able to assess and evaluate (See Table 1). I introduce Bloom’s Taxonomy to de-mystify what is going on in the college classroom. I use it to draw students’ attention to different ways of preparing for class, to the types of questions I may ask on homework assignments and exams and to ways they can work with the information they gather in this class. I am signaling to students that I am expecting them to do more than repeat back what I tell them. A couple of years ago I had a student who did quite well in my class. She said to me, “after the first exam I figured out what you were looking for.” Through Bloom’s Taxonomy I try to help all students figure out what college thinking involves and what I am expecting from them. Another way I signal to students that they are expected to achieve new levels of cognitive understanding and expressive performance is by labeling the first three written assignments as “portfolio components.” Artists demonstrate their competencies by assembling a portfolio of their work. Similarly, I suggest to my students that the work that they do in this class demonstrates their abilities and that each of these portfolio assignments allows them to demonstrate skills necessary for the study of religion. Each skill will also be needed to complete the final paper. I list on the syllabus what each portfolio component demonstrates. The first component – due the second or third class – demonstrates the ability to summarize the ideas of different authors. At a minimum this is about Comprehension, the second category on Bloom’s taxonomy. It can be a challenge to first-year college stu© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2004 Table 1: Bloom’s Taxonomy Knowledge Observation and recall information Knowledge of dates, events, places Knowledge of major ideas Mastery of subject material Question cues: list, define, tell, describe, identify, show, label, collect, examine, tabulate, quote, name, who, when, where, etc. Comprehension Understanding information Grasp meaning Translate knowledge into new context Interpret facts, compare, contrast Predict consequences Question cues: summarize, describe, interpret, contrast, predict, associate, distinguish, estimate, differentiate, discuss, extend Application Use information Use methods, concepts, theories in new situations Solve problems using required skills or knowledge Question cues: apply, demonstrate, calculate, complete, illustrate, show, solve, examine, modify, relate, change, classify, experiment, discover Analysis Seeing patterns Organization of parts Recognition of hidden meanings Identification of components Question cues: analyze, separate, order, explain, connect, classify, arrange, divide, compare, select, explain, infer Synthesis Use old ideas to create new ones Generalize from given facts Relate knowledge from several areas Predict, draw conclusions Question cues: combine, integrate, modify, rearrange, substitute, plan, create, design, invent, what if?, compose, formulate, prepare, generalize, rewrite Evaluation Compare and discriminate between ideas Assess value of theories, presentations Make choices based on reasoned argument Verify value of evidence Recognize subjectivity Question cues: assess, decide, rank, grade, test, measure, recommend, convince, select, judge, explain, discriminate, support, conclude, compare, summarize Prepared by the University of Victoria Counseling Services. Adapted from B. S. Bloom, ed., Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals: Handbook I, Cognitive Domain (New York: Longmans, Green, 1956). dents to summarize the main ideas of an essay and describe these ideas to their reader. In this assignment they must distinguish one author from another and the ideas of the authors from their own views. 226 Solvang The authors they read for this first assignment are Martin Luther King, Jr. and Anthony Weston. The articles are part of the way I introduce students to the ethical implications of religious convictions and challenge students to see themselves as social actors in a pluralistic world. In the chapter “Thinking for Yourself” in A Practical Companion to Ethics (Weston 1997, 13–27), Weston identifies three main sources for ethical decision-making: social norms, civic and professional authorities, and religious sources and authorities. He argues that individuals cannot merely accept what these sources say; they must actively engage in decisionmaking. In the essay “A Tough Mind and a Tender Heart” in Strength to Love (King 1988, 9–16), King argues that most people are “soft-minded” – unwilling to think critically, wanting to go with the crowd, fearful of change, pre-judging others, and easily manipulated. King argues that to act ethically one needs a tough mind and tender heart, a combination of critical reasoning and genuine compassion. Students like these two essays. Sadly, what they like best is not always in the essay. They agree with Weston that there are no fail-proof sources nor universally applicable truisms for ethical decision making, but they frequently reduce the “thinking for yourself” to “you have to do what you feel is right.” They like what Weston says but fail to recognize that what he says is not the same as what they are saying. With the King essay they resonate with the tender-heartedness but struggle even to remember the phrase “tough-minded.” It frequently comes out as “hard-minded” and they associate it with being mean. Some understand it as “making your own decisions.” All have a difficult time perceiving the process of critical thinking and the potentially costly conviction that King is challenging them to undertake. The students’ focus on feelings and their assumption that the authors see the world as they do are not surprising given the general profile of incoming students. The articles, the portfolio assignment, and the class discussion provide a starting point for considering the connection between critical thinking – particularly the role of questioning, reasoning, and consultation – and moral behavior. To help students recognize the decision-making that is a part of biblical interpretation and appreciate the ways interpretations shape understandings of self and others, we examine the history of apartheid in South Africa. Students read Desmond Tutu’s No Future Without Forgiveness, an account of the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa. As we begin discussing the book I have students recall what they were doing April 27, 1994 – the day of the first universal elections in South Africa. This question allows them to talk about their favorite subject – themselves. It also allows them to exist in the same time frame alongside the lives of people Tutu describes in the book. It opens a space for empathy and curiosity. Students will talk about disruptions, dislocations, and disappointments that occurred in their own lives that year, but they also recognize the relative safety and privilege of their lives and begin to express concern for the lives of these other people they meet through Tutu’s book. The empathic connection is hard to build. When I used Martin Luther King’s Strength to Love collection of essays as a class text, students loved the essays but could not grasp the political and theological context to which those essays were addressed. Frequently they would write about King “during the time of slavery.” They felt bad about what happened to him but they could not connect his legacy to their world. As we read Tutu’s book, I show students portions of two videos. One, from 1986, is Witness to Apartheid (Sopher 1986) narrated by Bill Moyers. This provides a graphic depiction of the unrest and violence in the townships, the indignities of the apartheid system, the level of military strength used to enforce apartheid and the profound separation of the worlds of white and black South Africans. Desmond Tutu is interviewed in the video so students can connect a voice and face to what they are reading. The video also presents on-the-street spot interviews with white South Africans. One woman, when asked what she thought about what was going on in the townships, replies, “I don’t really know. I think they are all happy.” My students always pick up on this, asking, “Did she not know or did she not want to know?” This is a question I would like my students to ask of their own lives. They are of the opinion that racism is a matter of personal intentions, immediately recognizable, and socially unacceptable. The video and the book help them see racism socially constructed, legally enforced, and the normative foundation for daily living. My students are rightfully repulsed by the assumptions, privileges, and damages of apartheid. They readily empathize with the South African blacks and puzzle over the behavior of most South African whites. This is an appropriate response and an indication of movement beyond their self-referential view of reality, but it is not yet critical thinking. They know apartheid is bad, but they cannot explain its existence or see patterns in this phenomenon that will enable them to recognize it in other contexts. In Bloom’s taxonomy these skills are components of Analysis. I indicated above that I believe reflection on the perspectives and traditions of the biblical world can assist students in reflecting on the values and practices of their own. When we are reading the book of Exodus we have the opportunity to make such a connection. Exodus begins by mentioning how the Israelites were fruitful and multiplied and grew exceedingly strong in the land of Egypt. Then the new king of Egypt says “Look, the Israelite people are more numerous and more powerful © Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2004 Thinking Developmentally than we. Come, let us deal shrewdly with them, or they will increase and, in the event of war, join our enemies and fight against us and escape from the land” (Exod. 1:9b-10). Fear drives the division between us and them. Fear creates a new oppressive social order. The authority of the king legitimates crimes against humanity as he instructs the midwives Shiphrah and Puah to kill every male Hebrew baby that they deliver. The midwives don’t fear the king, as one might expect, but fear God and spare the infant boys. A simple reading of this opening chapter of Exodus not only points to the central tension of fear of God vs. fear of Pharaoh and service to God vs. service to Pharaoh that structures the book of Exodus, but it invites reflection on how fear drives human behavior and supplies “reason” for oppression and violent aggression in the world today. In class discussion, connections are made between Pharaoh’s reasoning and the soft-mindedness that Martin Luther King, Jr. addresses in his essay and between the development of oppression in the Exodus text and the development of apartheid in South Africa. The midwives’ refusal to comply provides an opening for discussing tough-mindedness and the process of thinking that leads to a decision to resist. Students make connections not only to anti-apartheid efforts in South Africa but to other local, regional, and global examples. The second portfolio assignment asks students to read two psalms and a passage from Deuteronomy and “prepare a written summary of the expectations of the human king described there . . . and how the relationship between the king and God is depicted.” The skill being exercised here is one of analysis as they “demonstrate the ability to connect different perspectives from different biblical passages on the same topic.” However, I have discovered that for at least half of the students in a class this assignment challenges them at the level of Comprehension. As in the first portfolio assignment, they must distinguish between what they think about a subject and what someone else, that is, the Bible, actually says about it. Moreover they must assemble differing perspectives into a comprehensive statement. Much of what students claim about kingship in their portfolio papers is not what is said in these biblical passages. When we go over these texts in class some students chafe but most are genuinely surprised to discover on this topic that the Bible reflects not only a culture but a theology other than their own. Acknowledgment and comfort with genuine differences in perspective are elements of critical thinking that students need in order to read the Bible and relay its contents accurately to others. While there are limits to what one can claim a text says, there is a great deal of freedom in interpreting meaning and applying these texts. The third portfolio assignment allows students to exercise these skills. Stu© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2004 227 dents, working in groups, select a passage from the Gospel of Luke. They are to read about their passage in commentaries reflecting varying methodological approaches as well as gender, class, cultural, and denominational perspectives that I have placed on reserve in the library. Students are to examine their passage closely and develop their own view of the message of the passage. Then they are to present the passage to the rest of the class. I continue to be amazed not only by the creativity they invest in developing videos, PowerPoint presentations, skits, puppet shows, and dialogues to communicate their passages, but by their use of scholarly sources to explore differing possibilities for interpreting even familiar passages and by their enthusiasm and newly acquired ability to construct and explain their own interpretive choices. The passages presented allow prominent themes in Luke to become visible and alive. Students discover the ethical expectations of the Gospel. A key theme that emerges is the gospel’s invitation to those on the margins of society to enter fully into the community and the expectation that those in authority and privilege welcome them and rejoice over this reversal. This returns us to the challenge presented in Desmond Tutu’s No Future Without Forgiveness. How can those who have formerly existed on the margins of society enter fully into the community? And how can this reversal take place with rejoicing but without retaliation? Tutu argues that in South Africa this reversal can only take place through truth telling and renouncing the claim to retributive justice. Tutu’s book and video footage from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings, Facing the Truth (Pellett 1998), provide vivid testimony of South Africa’s attempt to emerge from destructive patterns of dealing with difference and to construct a new and different South Africa. Once again the video allows my students to empathize with the victims and puzzle over the motivations of those engaged in the violence. They are overwhelmed by the mercy extended by victims. Their written comments right after viewing the video include the following: “I cannot imagine being in either position of confessing or hearing what these people have done to others like you.” “I just don’t understand how a person could take part in this kind of behavior. I know they were ordered to do it but you’d think they would have enough sense not to. I just wonder what was going on in their heads.” “I kept wondering who thought of this idea of oppressing another race. After watching some of the testimonies of those who were oppressed I am finally beginning to realize what apartheid really is. I never thought about how brutal it actually was.” “It sickens me to know this was going on in my lifetime. I tried to place myself in the African’s position and I know I am 228 Solvang not a strong enough person to handle that. I also placed myself in the policeman’s position and I don’t think I would have been able to forgive myself.” The conditions and events described in Tutu’s book and depicted in the videos push students to ponder their own behavior. I am not interested in having students speculate on what they would have done if they were residents of South Africa. No one would imagine perpetrating crimes against humanity or being so folded within a social system so as not to see what was going on. However, I am interested in students considering how a system such as apartheid could “reasonably” be created, sustained, defended, and eventually dismantled. This type of critical thinking requires a Synthesis of knowledge from different areas. If students’ thinking about diversity is to be critical they must recognize that, though they lack the ability to imagine themselves perpetrating crimes against humanity, they do not lack the ability to act in those ways. Tutu asserts that ability in two theological claims that he says were essential to the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission: (1) “Each of us has this capacity for the most awful evil” (Tutu 1999, 85), and (2) “all of us . . . [have] this remarkable capacity for good, for generosity, for magnanimity” (Tutu 1999, 86). These claims challenge the dualistic thinking that firstyear students typically operate with, but they also make sense of what students have witnessed in the readings and in the videos about apartheid in South Africa. Moreover, students can relate these claims to what they have been reading in the Bible, where they read of crowds hailing Jesus that eventually shout for him to be crucified; where they hear a parable about a priest and a Levite inexplicably leaving a man for dead on the side of the road while an outsider, a Samaritan, chooses to respond in a generous and risky way. These claims also provide an opening for students to consider and discuss how they choose to treat those who have mistreated or offended them. To help students do this, I have students consider four statements about forgiveness that Tutu (1999) addresses: • there are some things that are unforgivable (260) • forgiving means forgetting (271) • confession is very helpful, but not absolutely necessary for someone to receive forgiveness (272) • forgiveness involves trying to understand the person who harmed you (271) As we discuss each statement, students move around the classroom to position themselves on a continuum from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” They are typically surprised by the visible range of opinions on each of these statements. I say very little. Students test whether these statements reflect Tutu’s argument. They share the reasons why they have chosen their place on the continuum. They question each other to understand each other’s position and explore the implications of those positions. On occasion students have shared poignant examples of forgiveness and the hope of reconciliation from their own lives. The goal of this exercise is not to get agreement on a right response, but to reinforce critical thinking as an essential factor in ethical behavior. Conclusion I have argued in this essay that for first-year college students to learn about Christianity and to become familiar with methods used in the study of religion they need to recognize and value diversity and acquire critical thinking skills. I have attempted to demonstrate how students might learn critical thinking skills as part of coming to understand the cultural otherness and theological complexity of the Bible and appreciating the ethical consequences of various biblical interpretations. In my discussion of the course I have tried to bring together teaching about diversity and teaching the skills needed to negotiate that diversity. The activities that I have described in this essay are intended to meet the goals of a course that is an “Introduction to Christianity and Religious Diversity.” The argument for teaching critical thinking and many of the activities designed to do that, however, are relevant to any religion class that includes first-year college students. It was necessity that pushed me to begin teaching critical thinking skills in my introductory class. Without these skills students are not capable of informed and articulate reflection on the content of the Bible, nor can they use their study of the biblical texts as a point for meaningful reflection on their participation in a pluralistic world. Over time I have become convinced that the teaching of critical thinking skills also belongs in an introductory religion class. Critical thinking skills need to develop within conversation about values, the human capacity for good and evil, and the diversity of human experience. References Chickering, Arthur W. and Reisser, Linda. 1993. Education and Identity. 2d ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. King, Martin Luther, Jr. 1988. Strength to Love. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. King, Patricia M. and Kitchener, Karen Strohm. 1994. Reflective Judgment Model of Intellectual Development in the College Years. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. Paul, Richard W. and Elder, Linda. 2002. Tools for Taking Charge of Your Professional and Personal Life. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall. © Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2004 Thinking Developmentally Pellett, Gail. 1998. Facing the Truth with Bill Moyers. New York: Public Affairs Television, Inc. 120 min. Videocassette. Perry, William G., Jr., 1999. Reprint. Forms of Intellectual and Ethical Development in the College Years: A Scheme. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. Original edition, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1968, 1970. Sopher, Sharon I. 1986. Witness to Apartheid. San Francisco: California Newsreel; Southern Africa Media Center. 56 min. Videocassette. Tutu, Desmond. 1999. No Future Without Forgiveness. New York: Image. © Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2004 229 University of Victoria Counseling Service Learning Skills Program, “Bloom’s Taxonomy,” 3 September 2003. <http://www.coun.uvic.ca/learn/program/hndouts/bloom. html> (5 April 2004). Adapted from Bloom, B. S., ed. 1956. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals: Handbook I, Cognitive Domain. New York: Longmans, Green. Weston, Anthony. 1997. A Practical Companion to Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.