Relative Potencies of Individual Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons to Induce Dioxinlike

advertisement

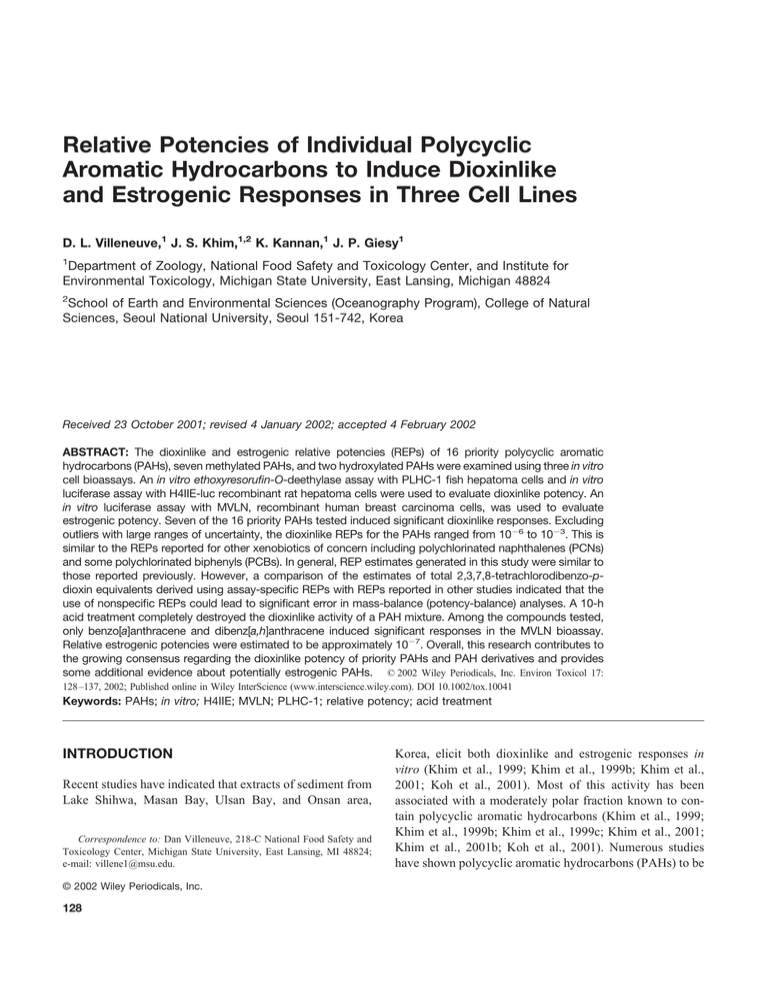

Relative Potencies of Individual Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons to Induce Dioxinlike and Estrogenic Responses in Three Cell Lines D. L. Villeneuve,1 J. S. Khim,1,2 K. Kannan,1 J. P. Giesy1 1 Department of Zoology, National Food Safety and Toxicology Center, and Institute for Environmental Toxicology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824 2 School of Earth and Environmental Sciences (Oceanography Program), College of Natural Sciences, Seoul National University, Seoul 151-742, Korea Received 23 October 2001; revised 4 January 2002; accepted 4 February 2002 ABSTRACT: The dioxinlike and estrogenic relative potencies (REPs) of 16 priority polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), seven methylated PAHs, and two hydroxylated PAHs were examined using three in vitro cell bioassays. An in vitro ethoxyresorufin-O-deethylase assay with PLHC-1 fish hepatoma cells and in vitro luciferase assay with H4IIE-luc recombinant rat hepatoma cells were used to evaluate dioxinlike potency. An in vitro luciferase assay with MVLN, recombinant human breast carcinoma cells, was used to evaluate estrogenic potency. Seven of the 16 priority PAHs tested induced significant dioxinlike responses. Excluding outliers with large ranges of uncertainty, the dioxinlike REPs for the PAHs ranged from 10⫺6 to 10⫺3. This is similar to the REPs reported for other xenobiotics of concern including polychlorinated naphthalenes (PCNs) and some polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). In general, REP estimates generated in this study were similar to those reported previously. However, a comparison of the estimates of total 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-pdioxin equivalents derived using assay-specific REPs with REPs reported in other studies indicated that the use of nonspecific REPs could lead to significant error in mass-balance (potency-balance) analyses. A 10-h acid treatment completely destroyed the dioxinlike activity of a PAH mixture. Among the compounds tested, only benzo[a]anthracene and dibenz[a,h]anthracene induced significant responses in the MVLN bioassay. Relative estrogenic potencies were estimated to be approximately 10⫺7. Overall, this research contributes to the growing consensus regarding the dioxinlike potency of priority PAHs and PAH derivatives and provides some additional evidence about potentially estrogenic PAHs. © 2002 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Environ Toxicol 17: 128 –137, 2002; Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI 10.1002/tox.10041 Keywords: PAHs; in vitro; H4IIE; MVLN; PLHC-1; relative potency; acid treatment INTRODUCTION Recent studies have indicated that extracts of sediment from Lake Shihwa, Masan Bay, Ulsan Bay, and Onsan area, Correspondence to: Dan Villeneuve, 218-C National Food Safety and Toxicology Center, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824; e-mail: villene1@msu.edu. © 2002 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. 128 Korea, elicit both dioxinlike and estrogenic responses in vitro (Khim et al., 1999; Khim et al., 1999b; Khim et al., 2001; Koh et al., 2001). Most of this activity has been associated with a moderately polar fraction known to contain polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (Khim et al., 1999; Khim et al., 1999b; Khim et al., 1999c; Khim et al., 2001; Khim et al., 2001b; Koh et al., 2001). Numerous studies have shown polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) to be RELATIVE POTENCIES OF INDIVIDUAL PAHS capable of inducing dioxinlike responses in vitro in both fish (Villeneuve et al., 1998; Bols et al., 1999, Fent and Bätscher, 2000; Behrens et al., 2001; Jung et al., 2001) and mammalian cell lines (Willett et al., 1997; Clemons et al., 1998; Jones and Anderson, 1999). PAHs have also been shown to induce ethoxyresorufin-O-deethylase (EROD) activity in vivo (Gerhart and Carlson, 1978; Brunström et al., 1991; Blanchard et al., 1999; Basu et al., 2001). Three PAHs— benzo[a]pyrene (BAP), chrysene (CHR), and benzo[a]anthracene (BAA)— have been reported to elicit estrogenic responses in vitro (Clemons et al., 1998). Because the sediment extracts were complex mixtures of trace organic compounds including, but not limited to, PAHs, it was unclear whether PAHs present in the extracts could account for the dioxinlike and estrogenic responses observed. Both novel and/or known aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and estrogen receptor (ER) agonists that eluted in the midpolar fraction could have contributed to the responses. Mass-, or potency-, balance analysis is one approach for addressing whether the known composition of a chemical mixture, as measured by instrumental analysis, can account for the potency and/or the magnitude of the biological response observed (Sanderson and Giesy, 1998). Until now, mass-balance studies of Korean sediment and other environmental samples have relied on the relative potencies (REPs) of PAHs reported in the literature. Although such values are useful for comparative purposes and for the development of consensus values for use in risk assessments, they are not ideal for mass-balance analysis. Ideally, mass- balance analysis should be based on REPs that are species-, end-point-, and assay specific (Sanderson and Giesy, 1998). The use of consensus values such as toxic equivalency factors (TEFs) or nonspecific REPs can lead to considerable error in mass-balance conclusions (Sanderson and Giesy, 1998). Thus, the goal of this study was to develop assay-specific REPs for the dioxinlike and estrogenic potencies of individual PAHs that could be used for subsequent mass-balance analyses. This article reports assay-specific REPs for 16 priority PAHs (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [EPA], method 8310), seven methylated PAH compounds, and two hydroxylated PAH compounds. The dioxinlike potency of each compound to induce EROD activity in PLHC-1 fish hepatoma cells (Hahn et al., 1993; Ryan and Hightower, 1994; Hahn et al., 1996) and in vitro luciferase activity in H4IIE-luc recombinant rat hepatoma cells (Sanderson et al., 1996) was evaluated. Estrogenic potency to induce in vitro luciferase activity in MVLN cells (Pons et al., 1990; Demirpence et al., 1993) was also characterized. REPs derived in this study were compared to those reported elsewhere, and the potential implications for mass-balance analysis were considered. A mixture of 16 priority PAHs was treated with acid and analyzed by in vitro bioassay to examine the utility of acid treatment for bioassay-directed fractionation studies of PAHs and to test the hypothesis that acid-breakdown 129 products of PAHs may elicit dioxinlike responses in vitro. Finally, the effect of exposure duration on the in vitro potency of PAHs was examined. The REPs presented contribute to a growing body of PAH REPs in the literature that can be used to develop consensus values for risk assessment. The information presented here should aid future research aimed at determining the relative contribution of individual PAHs to the total dioxinlike and/or estrogenic activities associated with sediment extracts and other environmental samples. MATERIALS AND METHODS Chemicals All PAHs, PAH metabolites, and PAH mixtures used in this study (Table I) were obtained from AccuStandard (New Haven, CT). Concentrations tested in the bioassays varied (Table I) and were limited by the mass of standard available. The maximum concentrations of the 16 priority, seven methylated, and two hydroxylated PAHs tested in the in vitro bioassays were 400, 10, and 20 g/mL, respectively. For the bioassay six dilutions of each standard were prepared by threefold serial dilution of the concentrated stock. All dilutions were prepared in high-purity acetonitrile and/or hexane (Burdick and Jackson, Muskegon, MI). The PAH mixture used for this study was 99% pure and consisted of the following PAHs: acenapthene, acenapthylene, anthracene, BAA, BAP, benzo[b]fluoranthene (BBF), benzo[ghi]perylene, benzo[k]fluoranthene (BKF), CHR, dibenz[ah]anthracene (DBA), fluoranthene, fluorene, indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene (IP), naphthalene, phenanthrene, and pyrene. Acid Treatment A mixture of 16 priority PAHs was treated with concentrated H2SO4 (1:1 PAH mixture:acid). Two treatment durations (1 h and 10 h) were tested. After the appropriate exposure duration, the solvent layer was removed for bioassay analysis. One set of solvent layers was rinsed with nanopure water (1:1 water:sample) prior to bioassay, while another set was assayed directly without the washing step. Acid-treated samples were tested at a single concentration (a 100-ppb mixture). GC/MS analysis (selected ion monitoring mode) was used to evaluate the destruction of PAH parent compounds by acid treatment. The specific details of the GC/MS column and the operating conditions were the same as those described for previous studies (Khim et al., 1999, 1999c). Cell Culture and Bioassay PLHC-1 cells are desert topminnow (Poeciliopsis lucida) hepatoma cells that have been shown to have inducible 130 VILLENEUVE ET AL. TABLE I. Maximum concentrations of individual PAHs tested in PLHC-1, H4IIE-luc, and MVLN in vitro bioassays, greatest magnitude of induction relative to a 2,3,7,8-tetrachlordibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) standard, and relative potency (REP) estimatesa PLHC-1 EROD PAH Compounds Acenapthene Acenapthylene Antracene Benzo[a]anthracene Benzo[a]pyrene Benzo[b]fluoranthene Benzo[g,h,i]perylene Benzo[k]fluoranthene Chrysene Dibenz[a,h]anthracene Fluoranthene Fluorene Indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene Napthalene Phenanthrene Pyrene 9-Methyl anthracene 9,10-Dimethyl anthracene 3,9-Dimethyl benzo[a]anthracene 1-Methyl naphthalene 1,2-Dimethyl naphthalene 3,6-Dimethyl phenanthrene 2-Methyl benzo[c]phenanthrene 6-Hydroxy chrysene 1-Hydroxy pyrene Max. Conc. (ppb in well) b % max 4000 4000 4000 4000 4000 4000 4000 4000 4000 4000 4000 4000 4000 4000 4000 4000 100 1 0 2 23 9 86 1 70 62 110 1 1 36 1 2 2 0 100 REP20–80 c H4IIE-luc d REP e % max REP20–80 REP NA NA NA 6.0 ⫻ 10⫺7 4.2 ⫻ 10⫺9 7.3 ⫻ 10⫺5 NA 4.9 ⫻ 10⫺4 2.6 ⫻ 10⫺5 3.8 ⫻ 10⫺3 NA NA 4.1 ⫻ 10⫺5 NA NA NA NA 0 0 0 60 54 54 2 92 62 83 0 0 72 0 8 0 0 1 NA 0 100 100 0 0 NA NA 12 0 100 0 NA 0 NA 100 25 3.7 ⫻ 10⫺4–1.8 ⫻ 10⫺6 2.6 ⫻ 10⫺5 0 NA 100 200 200 2 32 6 2.3 ⫻ 10⫺4–3.8 ⫻ 10⫺6 NA 2.9 ⫻ 10⫺5 NA 0 0 0 NA NA NA 1.2 ⫻ 10⫺5–2.9 ⫻ 10⫺8 3.8 ⫻ 10⫺6–4.6 ⫻ 10⫺12 1.2 ⫻ 10⫺4–4.5 ⫻ 10⫺5 1.1 ⫻ 10⫺3–2.2 ⫻ 10⫺4 7.5 ⫻ 10⫺5–8.8 ⫻ 10⫺6 5.1 ⫻ 10⫺3–2.8 ⫻ 10⫺3 1.8 ⫻ 10⫺4–9.2 ⫻ 10⫺6 2.2 ⫻ 10⫺6–1.7 ⫻ 10⫺6 2.4 ⫻ 10⫺6–1.1 ⫻ 10⫺6 1.6 ⫻ 10⫺5–1.6 ⫻ 10⫺6 3.9 ⫻ 10⫺4–5.1 ⫻ 10⫺5 4.6 ⫻ 10⫺6–1.2 ⫻ 10⫺6 4.4 ⫻ 10⫺5–4.8 ⫻ 10⫺7 3.4 ⫻ 10⫺5–6.4 ⫻ 10⫺6 NA NA NA 1.9 ⫻ 10⫺6 1.6 ⫻ 10⫺6 5.1 ⫻ 10⫺6 NA 1.4 ⫻ 10⫺4 2.3 ⫻ 10⫺6 4.6 ⫻ 10⫺6 NA NA 1.5 ⫻ 10⫺5 NA NA NA NA NA 6.0 ⫻ 10⫺7–8.7 ⫻ 10⫺14 2.3 ⫻ 10⫺10 NA a Only two PAHs (benzo[a]anthracene and dibenz[ah]anthracene) induced responses in the MVLN bioassay; thus, MVLN REPs are not included here. % max ⫽ maximum response observed expressed as a percentage of the mean maximum response observed for the TCDD standard (% TCDD max). Maximum response was not necessarily achieved at the maximum concentration tested. c REPs are reported as the range of REP estimates generated from multiple point estimates over a response range from 20% to 80% TCDD max (REP20 – 80 range). d Single point estimate of REP made for a response of 50% TCDD max (EC-50). e NA: not able to calculate REP; dose–response relationship insufficient for estimate. b cytochrome P4501A1 activity (Hightower and Renfro, 1988; Hahn et al., 1993, 1996). H4IIE-luc cells are rat hepatoma cells that have been stably transfected with a luciferase reporter gene under the control of dioxin-responsive enhancers (DREs) (Sanderson et al., 1996). MVLN cells are MCF-7 human breast carcinoma cells stably transfected with a luciferase reporter gene under the control of estrogen responsive elements (EREs) of the Xenopus vitellogenin A2 gene (Pons et al., 1990; Demirpence et al., 1993). The culturing conditions for all three cell lines have been described previously (Khim et al., 1999; Villeneuve et al., 2001). In vitro EROD assay with PLHC-1 cells and in vitro luciferase assay with H4IIE-luc and MVLN cells have also been described (Khim et al., 1999; Villeneuve et al., 2001). Briefly, cells were trypsinized from Petri plates containing 80%–100% confluent monolayers and resuspended in media at the density desired for seeding. Cells were seeded into 96 well microplates, allowed to attach overnight, and then dosed. Test and control wells received 2.5 L of the appropriate sample or solvent. Blank wells received no dose. Dose responses consisted of six concentrations prepared by threefold serial dilution. All samples were tested in triplicate, and a minimum of three blank and three solvent control wells were run on each 96-well test plate. Cells were exposed for 72 h (except for time-course experiments), and then in vitro EROD or luciferase assays were run as described elsewhere (Khim et al., 1999; Villeneuve et al., 2001). Time-Course Experiments A mixture of 16 PAHs (PLHC-1 and H4IIE-luc assays) or BAA (MVLN assay) was tested after four different expo- RELATIVE POTENCIES OF INDIVIDUAL PAHS sure durations. Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at the normal density used for a 72-h exposure. Four plates were seeded for each sample (for each of the three assays). One of the plates was dosed the morning after seeding (72-h exposure), a second 24 h later (48 h), a third 48 h later (24 h), and the final plate 60 h later (12 h). Bioassays were conducted exactly 72 h after the first dosing event. This dosing approach was employed for both the PAH samples and the 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) and 17-estradiol (E2) standards. This approach was chosen because it assured a uniform stock of cells, uniform incubation duration, and uniform reagent and instrument conditions for the assays while allowing for variable durations of exposure to the test compound. Response magnitudes, expressed as % TCDD max or % E2 max, and REP estimates calculated from the time-course experimental results were based on comparison to a TCDD or E2 standard exposed for the same duration. 131 the response level selected (Putzrath, 1997). The minimum and maximum REPi values generated (a relative potency, or REP20 – 80, range) were reported as an estimate of the uncertainty in the relative potency estimate due to deviations from parallelism between the standard and sample curves (Villeneuve et al., 2000). In cases where the observed maximum response for the sample was less than 80% TCDD/E2 max, extrapolation beyond the range of the empirical results was used to estimate REPi at Yi greater than the observed maximum. This was done in order to make the REP20 – 80 ranges comparable from sample to sample, because the magnitude of the range is dependent on the range of responses over which it is calculated (Villeneuve et al., 2000). REP20 – 80 ranges were reported along with a conventional REP based on a single point estimate determined at 50% TCDD/E2 max. in order to provide an indication of the uncertainty of the estimate (Villeneuve et al., 2000). RESULTS Bioassay Data Analysis Sample responses expressed as mean relative luminescence units (RLU) or mean pmol min⫺1 mg⫺1 (three replicate wells) were converted to a percentage of the mean maximum response observed for standard curves generated on the same day (% TCDD max or % E2 max). This was done to normalize for day-to-day variability in response magnitude and to make response magnitudes comparable from assay to assay. The mean solvent control response was subtracted from both the sample and the TCDD or E2 standard responses prior to conversion to a percentage in order to scale the values from 0% to 100% TCDD/E2 max. In cases in which the magnitude of induction was sufficient to allow a quantitative estimate, assay-specific REPs were calculated. The linear portion of each dose response (% TCDD/E2 max, plotted as a function of log dose) was defined by dropping points from the tails until an R2 ⱖ 0.95 was obtained and a linear regression model was fit to the remaining points. At least 3 points were used in all cases. The linear regression equations for the samples and the corresponding TCDD or E2 standard were used to estimate the concentration associated with responses, expressed as % TCDD/E2 max. For point estimates of relative potency to be valid, the sample and the standard dose response must be statistically parallel and have the same maximum achievable response (Finney, 1978; Putzrath, 1997). These conditions were tested empirically. The efficacy of many of the samples was either unknown or less than that of either the TCDD or E2. Thus, equal efficacy could not be assumed. The parallel slopes assumption was tested by calculating relative potencies (REPi) at multiple levels of response (Yi) ranging from 20% to 80% TCDD max (Villeneuve et al., 2000). For parallel dose responses, REP estimates are independent of Relative Potency of Individual PAHs At the concentrations tested, seven of the 16 priority PAHs tested elicited significant dioxinlike responses in both the PLHC-1 EROD and H4IIE-luciferase assays (Table I). All active PAHs contained at least four rings. DBA yielded both the greatest magnitude of response and the most potent response (an REP of approximately 10⫺3) in the PLHC-1 bioassay (Table I). DBA also yielded the greatest magnitude of response in the H4IIE-luc assay but had an REP approximately 1000 times less than that determined in the PLHC-1 assay (Table I). BKF, with an REP around 10⫺4, was the most potent PAH tested in the H4IIE-luc bioassay. BKF was similarly potent in the PLHC-1 assay (Table I). Other priority PAHs that exhibited dioxinlike activity included BAA, BAP, BBF, CHR, and IP (Table I). Among the seven methylated and two hydroxylated PAH compounds tested, three compounds induced a significant dioxinlike response (Table I). These were 3,9-dimethylbenzo[a]anthracene (DMBA), 3,6-dimethylphenanthrene, and 6-hydroxychrysene. At the concentrations tested, none of the three compounds induced significant responses in both the PLHC-1 and the H4IIE-luc bioassay. 3,6-Dimethylphenanthrene and 6-hydroxychrysene were both active in the PLHC-1 bioassay and exhibited relative potencies similar to those derived for parent PAH compounds (REP ⯝ 10⫺5). DMBA induced a significant response in the H4IIEluc bioassay, but the relatively low magnitude of response observed resulted in great uncertainty in the REP estimate. Based on the dose responses obtained, the approximate H4IIE-luc-derived REP for DMBA was 10⫺10 (Table I). Relatively few of the individual PAHs and substituted PAHs tested induced a significant estrogenic response in the MVLN bioassay. Among the 16 priority PAHs tested, only 132 VILLENEUVE ET AL. acid treatment reduced the activity to a level not significantly different from that induced by the solvent control (Fig. 1). Washing of acid-treated extracts appeared to further decrease the dioxinlike activity of the PAH mixture (Fig. 1). GC/MS analysis of acid-treated mixtures of 16 priority PAHs indicated that a 1-h acid treatment destroyed more than 99% of the 16 parent PAHs. The 10-h acid treatment destroyed 100% of the parent PAHs. Effect of Exposure Duration on PAH Relative Potencies Fig. 1. Luciferase induction in the H4IIE-luc cell bioassay elicited by acid-treated and nontreated mixtures of 16 priority PAHs. Response magnitude presented as a percentage of the maximum response observed for a 3130 pM TCDD standard (% TCDD max). Washed ⫽ the extract was rinsed with nanopure water prior to bioassay; no wash ⫽ the extract was not rinsed prior to bioassay; error bars ⫽ standard deviation (SD); sig. ⫽ magnitude of response equal to 3 SD above the mean solvent control response (0% TCDD max). BAA and DBA induced a significant response. The maximum magnitudes of response observed were 24% and 25% E2 max for BAA and DBA, respectively. Both compounds were estimated to be more than a million times less potent than E2 (REP50 ⫽ 5.7 ⫻ 10⫺7 for BAA, REP50 ⫽ 8.8 ⫻ 10⫺7 for DBA). At the concentrations tested, none of the methylated or hydroxylated PAHs induced a significant response in the MVLN bioassay. Most REP estimates generated for the priority PAHs had uncertainty ranges that varied by less than a factor of 10 (Table I). Notable exceptions were PLHC-1-derived REP estimates for BAA and BAP, which had uncertainty ranges in excess of 100-fold because of the relatively low magnitudes of induction observed. The PLHC-1-derived REP for IP and H4IIE-luc-derived REP both had uncertainties greater than 10-fold but less than 100-fold over the EC-20 – EC-80 response range (Table I). The same was true for PLHC-1-derived REP estimates for 3,6-dimethylphenanthrene and 6-hydroxychrysene (Table I). The REP estimate derived for DMBA had the greatest uncertainty (more than a million- fold). Uncertainty ranges for MVLN-derived REP estimates were both less than eightfold. Dioxinlike Activity of Acid-Treated PAHs Acid treatment was shown to reduce the dioxinlike activity of a mixture of 16 priority PAHs in a time-dependent fashion (Fig. 1). An hour of acid treatment reduced the dioxinlike activity of the PAH mixture to a level approximately 50% of the nontreated activity (Fig. 1). The 10-h The relative estrogenic potency of BAA and the dioxinlike potency of a mixture of 16 priority PAHs decreased with increased duration of in vitro exposure (Fig. 2). After a 12-h exposure, BAA had produced a maximal response that was 130% of that obtained for a 1000-pM E2 standard (Fig. 2) and was estimated to have a MVLN-derived REP of 1.4 ⫻ 10⫺5 (Fig. 2). After a 72-h exposure, the maximal response (relative to E2 max) was less than 10% of that observed after 12 h (Fig. 2), and an REP estimate could not be derived. The maximal H4IIE-luc-derived REP for the mixture of 16 PAHs was observed after a 24-h exposure (Fig. 2). Longer exposure durations yielded dose-response relationships exhibiting similar efficacy (relative to TCDD) but reduced relative potency, as indicated by a shift of the dose-response curves to the right along the x-axis (Fig. 2). In the PLHC-1 assay the 16-PAH mixture yielded dose responses with an inverted U shape (Fig. 2). Similar results have been observed in previous studies and may be a result of substrate inhibition (Hahn et al., 1993). As observed for the H4IIE-luc assay, the dose-response curves were progressively shifted to the right as exposure duration increased (Fig. 2), indicating reduced potency relative to a TCDD standard. Thus, for at least some PAHs, in vitro REP appeared to decrease with increased exposure duration. DISCUSSION Relative Potency Estimates Dioxinlike REPs were derived for 7 of the 16 priority PAHs examined in this study. The range of uncertainty over a range of responses from EC-20 to EC-80 was relatively small for most estimates, indicating reasonable conformity to the parallel slopes assumption inherent in REP estimation (Putzrath, 1997; Finney, 1978; Villeneuve et al., 2000). Thus, most of the estimates reported should be suitable for use in assay-specific mass-balance analyses. Several of the estimates, including the PLHC-1-derived estimates for BAA and IP and the H4IIE-luc-derived estimate for DBA had greater than 10-fold uncertainty ranges. This was also the case for PLHC-1-derived REPs for 3,6-dimethylphenanthrene and 6-hydroxychrysene. Such estimates may be use- RELATIVE POTENCIES OF INDIVIDUAL PAHS 133 ful for assay-specific mass-balance analysis but should be applied with careful consideration of the limitations and uncertainties associated with the estimates. Most of the more uncertain REP estimates (excluding the H4IIE-derived REP for DBA) were derived from dose-response relationships exhibiting efficacy of less than 40% TCDD max. Thus, the REP20 estimates should be considered the most reliable estimate of relative potency. Mass-balance assessments incorporating these values may be more accurate if based on EC-20 (or sub-EC-50) responses. The PLHC-1derived REP for BAP and the H4IIE-luc-derived REP estimate for DMBA were both highly uncertain and should probably be recharacterized before being used extensively for mass-balance analysis. Both MVLN-derived REPs should be useful for mass-balance applications. The dioxinlike potency of individual PAHs was similar to the potencies reported for a range of other AhR-active environmental contaminants. Most of the PAHs examined in this study had REPs in the range of 10⫺4 to 10⫺6 for inducing dioxinlike responses in the PLHC-1 and H4IIE-luc bioassays. This was similar to the range of H4IIE-derived REPs reported for pentachlorinated naphthalenes (CNs) and slightly less than that reported for hexa-CNs (Villeneuve et al., 2000b). The REPs determined for individual PAHs were generally greater than the H4IIE-derived REPs reported for complex mixtures of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polychlorinated naphthalenes (PCNs; Villeneuve et al., 2001). REPs for individual PAHs were also similar to those for coplanar PCBs. The two estrogenic PAHs characterized in this study had estrogenic potencies similar to those reported for other environmental xenoestrogens of concern, including nonylphenol, octylphenol, and bisphenol A (Villeneuve et al., 1998). This relative order of potency, along with the wide distribution of PAH contamination in the environment, suggests that certain PAHs should be considered in assessments of total TCDD equivalents (TEQs) or estrogen equivalents (EEQs) present in environmental samples. Acid Treatment Fig. 2. Response of MVLN bioassay to benzo[a]anthracene and H4IIE-luc and PLHC-1 bioassays to a mixture of 16 priority PAHs after 4 exposure durations (12, 24, 48, and 72 h). Relative potency (REP) estimates calculated at the EC-50 response level are presented in parentheses. Response magnitudes, expressed as % TCDD max or % E2 max, and REP estimates were based on comparison to a TCDD or a 17-estradiol standard exposed for the same duration. Sig. ⫽ magnitude of response equal to 3 SD above the mean solvent control response. Past bioassay-directed fraction/toxicant identification studies have used acid treatment to separate the effects of acid-labile compounds such as PAHs from those of acidstable compounds such as polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and polychlorinated dibenzofurans (Khim et al., 1999b). These assessments relied on the assumptions that a 1-h treatment with concentrated H2SO4 would breakdown priority PAHs and that the resulting acid-breakdown products would not produce dioxinlike in vitro bioassay responses. Results of this study indicate that significant PAH breakdown (approximately 99%) can be achieved with a 1-h acid treatment, but that longer treatment duration may be required to completely eliminate dioxinlike responses (Fig. 2). 134 VILLENEUVE ET AL. It was not clear whether the bioassay responses observed after 1 h of acid treatment were a result of the continued presence of small amounts of relatively potent parent PAHs or of the production of acid-breakdown products capable of eliciting dioxinlike responses. Either way, the 10-h acid treatment appeared to destroy all AhR-active PAHs and/or PAH derivatives. The duration of treatment needed to completely eliminate PAH contributions to dioxinlike in vitro responses may be modulated by the total concentration of PAHs present, the relative acid stabilities of the PAHs or PAH derivatives present, and the relative potencies of the more stable compounds. Rinsing acid-treated extracts with nanopure water appeared to further reduce carryover of active PAHs into the acid-treated product. Thus, results of this study suggest that 10 h or longer of acid treatment followed by a water rinse should serve as an effective method for separating the effects of priority PAHs from those of other acid-stable compounds. Effect of Exposure Duration on PAH Relative Potencies In the time-course experiments there was a general trend toward decreased relative potency with increased duration of exposure. This could be explained by either in vitro degradation of PAHs (greater exposure duration allowing for greater degradation) or increased potency of the E2 or TCDD standard relative to PAH potency over greater exposure duration. In the MVLN bioassay BAA efficacy and potency (in absolute units, i.e., RLU) decreased with increased exposure duration, whereas the efficacy and potency of E2 was greater after 48 and 72 h than after 12 and 24 h. This suggests that for the MVLN bioassay, both BAA degradation and a relative increase in E2 potency may have contributed to the general decline in the relative estrogenic potency of BAA with increased exposure duration. In the H4IIE-luc bioassay the efficacy and potency (in absolute units, i.e., RLU) of both the TCDD standard and the PAH mixture increased with exposure duration. This suggests that PAH degradation was probably not a significant contributor to the general decline in the H4IIE-luc-derived REP over time. In the PLHC-1 assay TCDD efficacy and potency (in absolute units, i.e., pmol min⫺1 mg⫺1) increased steadily with exposure duration, whereas those of the PAH mixture remained approximately stable from 12 to 48 h and then declined significantly after 72 h. This result suggests that the increased potency of TCDD was the primary reason for the observed decrease in REP observed for the 12– 48 h PLHC-1 exposures. The significant decline after 72 h was most likely caused by inactivation of some of the PAH mixture after 72 h of exposure. Overall, the results of the time-course experiments conducted as part of this study indicated that in vitro bioassay-derived relative potency and efficacy estimates can vary significantly as a function of the exposure duration employed. This potential for variability supports the contention that mass-balance analyses should be based on assay-specific REPs derived using the same exposure duration as that used for the sample analysis. Comparison of PAH REPs For the priority PAHs, the list of compounds that have been found to express AhR-mediated effects is similar among studies (Table II). BAA, BAP, BBF, BKF, and CHR have been universally shown to induce dioxinlike responses in a variety of in vitro bioassays (Table II). Furthermore, most studies have reported that DBA and IP are AhR-active in vitro (Table II). The concentrations tested by Villeneuve et al. (1998) were 8 times less than those used in this study. The REP for anthracene has been reported by Clemons et al. (1998) to be approximately 10⫺4. This was the only PAH for which there was not strong consensus in the literature. Comparison of the in vitro REPs currently available suggests that anthracene should probably not be included in risk assessments or mass-balance analyses aimed at estimating the total dioxinlike potency contributed by PAHs. This observed consensus among in vitro studies generally holds for REP estimates as well. None of the studies examined predicted the same rank order of potency for the AhR-active PAHs listed in Table II. A general blocking of certain compounds was observed, however. BKF and DBA were ranked among the three most potent PAHs by seven of the eight studies compared (Table II). CHR and BAA were ranked among the three least potent PAHs in all but the hepa cell bioassay (Table II). Variation in REP estimates was generally less than 2 orders of magnitude (Table II). If only fish cell line– derived REP values are compared, most estimates vary by 1 order of magnitude or less for each compound (Table II). Among the fish cell bioassays, the PLHC1-derived REP estimates generated for BAA and BAP in this study appeared to be the only significant outliers (Table II). Studies by Bols et al. (1999) and Fent and Bätscher (2000) used 24-h exposure durations, whereas the study reported here used an exposure of 72 h. Thus, the lesser REP observed for BAA and BAP may be associated with the longer exposure time. REPs of 72 h estimated in a previous study by Villeneuve et al. (1998) were similar to the Fent and Bols estimates, however. Furthermore, the H4IIE-luc-derived estimates generated in this study were similar to other mammalian-cell REPs reported for BAA and BAP. Thus, the explanation for the relatively low potency of BAA and BAP in the PLHC-1 assay employed in this study remains unknown. For mammalian-cell lines the poorest agreement among studies was observed for BKF, CHR, and DBA. Estimates of REP for these compounds varied over 4 orders of magnitude (Table II). In the absence of a rationale for weighting any one study greater than others, additional determinations using other mammalian- RELATIVE POTENCIES OF INDIVIDUAL PAHS 135 TABLE II. Comparison of relative potency (REP) values reported for individual PAHs. REPs shown were calculated relative to a TCDD standard [only EPA priority PAHs (EPA method 8310) that had caused significant induction in at least one study are included] PAH Anthracene Benzo[a]anthracene Benzo[a]pyrene Benzo[b]fluoranthene Benzo[k]fluoranthene Chrysene Dibenz[a,h]anthracene Indeno[1,2,3-c,d]pyrene PLHC-1a PLHC-1b PLHC-1c RTL-W1d H4IIE-luca H4IIEe Humanf Hepag NI 4.2 ⫻ 10⫺7 3.3 ⫻ 10⫺9 5.7 ⫻ 10⫺5 3.8 ⫻ 10⫺4 1.8 ⫻ 10⫺5 3.3 ⫻ 10⫺3 3.5 ⫻ 10⫺5 NI 1.7 ⫻ 10⫺5 1.65 ⫻ 10⫺4 NA 9.9 ⫻ 10⫺4 9.6 ⫻ 10⫺5 3.3 ⫻ 10⫺3 NA NI 7.1 ⫻ 10⫺5 4.2 ⫻ 10⫺4 3.0 ⫻ 10⫺4 7.5 ⫻ 10⫺4 1.1 ⫻ 10⫺4 NI NI NI 4.3 ⫻ 10⫺5 3.0 ⫻ 10⫺4 1.9 ⫻ 10⫺4 1.0 ⫻ 10⫺3 4.7 ⫻ 10⫺5 3.5 ⫻ 10⫺4 2.8 ⫻ 10⫺4 NI 1.4 ⫻ 10⫺6 1.3 ⫻ 10⫺6 4.0 ⫻ 10⫺6 1.1 ⫻ 10⫺4 1.6 ⫻ 10⫺6 4.0 ⫻ 10⫺6 1.3 ⫻ 10⫺5 NA 2.5 ⫻ 10⫺5 3.5 ⫻ 10⫺4 2.5 ⫻ 10⫺5 4.8 ⫻ 10⫺3 2.0 ⫻ 10⫺4 2.0 ⫻ 10⫺3 1.1 ⫻ 10⫺3 NI 3 ⫻ 10⫺6 8 ⫻ 10⫺6 2 ⫻ 10⫺6 2 ⫻ 10⫺4 3 ⫻ 10⫺6 4 ⫻ 10⫺5 2 ⫻ 10⫺5 1 ⫻ 10⫺4 1 ⫻ 10⫺5 1 ⫻ 10⫺5 NA 5 ⫻ 10⫺2 1 ⫻ 10⫺2 5 ⫻ 10⫺2 NA NA ⫽ not analyzed. NI ⫽ no significant induction at the concentrations tested in the study. All REPs shown here were calculated on a molar concentration basis and were based on the EC-50s estimated for the PAH and for the standard compound. a This study. b Fent and Bätscher, 2000. Originally reported as induction equivalency factors (IEF) relative to dibenzo[ah]anthracene. For comparability values were multiplied by 3.3 ⫻ 10⫺3 (the PLHC-1 REP relative to the TCDD generated in this study). Values should be considered approximate. c Villeneuve et al., 1998. d Bols et al., 1999; Rainbow trout liver cell line. e Willet et al., 1997. f Jones and Anderson, 1999. g Clemons et al., 1998. cell bioassays or similar assays in other laboratories will be needed to develop consensus values for the mammalian-cell REP of BKF, CHR, and DBA. Overall, however, the PAH REPs currently available in the literature provide a reasonable data set for the formulation of consensus values for the dioxinlike REP of priority PAHs. To date, only two studies, that of Clemons et al., (1998) and this study, have reported the relative estrogenic potency of priority PAHs. BAA was the only priority PAH that produced an estrogenic response in both studies. REP estimates for BAA were 5.7 ⫻ 10⫺7 and 1.0 ⫻ 10⫺4 in this study and in the Clemons et al. (1998) study, respectively. DBA (this study), CHR, and BAP (Clemons et al., 1998) induced a significant estrogenic response in one of the studies, but not both. Additional studies will be needed to develop consensus values for the in vitro estrogenic potency of PAHs. and to evaluate whether use of assay-specific REPs was necessary. Variability in excess of 300-fold was observed (Table III; i.e., H4IIE-luc-derived values in this study vs. those found in Clemons et al., 1998). Among similar mammalian cell bioassays (i.e., H4IIE-EROD-Willett and H4IIE-luc-Villeneuve), TEQ estimates differed by nearly 100-fold (Table III). Among two fish cell bioassays (RTLW1-Bols and PLHC-1-Villeneuve) an approximately fourfold difference in TEQ estimates was observed (Table III). Results of this analysis support the conclusion that use of nonspecific REPs for mass-balance analysis could lead to significant error and inaccurate conclusions. Assay-specific REPs should be employed for mass-balance assessments, and wherever possible, uncertainties in the REP estimates themselves should be considered. CONCLUSIONS REP Variability and Mass-Balance Implications The rationale for this study was predicated on the assumption that assay-specific REPs should be used for massbalance (potency-balance) analyses involving PAHs. Thus, assay-specific REPs generated in this study, as well as those reported in three other studies (Willett et al., 1997, Clemons et al., 1998, and Bols et al., 1999) were used to calculate total TEQs for some model environmental samples containing complex mixtures of PAHs (Table III). This was done to determine the magnitude of impact that the variability in REP estimates would have on typical TEQ determinations Several priority PAHs and hydroxylated or methylated PAH derivatives induced dioxinlike responses in the PLHC-1, H4IIE-luc in vitro bioassays, and/or estrogenic effects in the MVLN bioassay. Relative potencies of AhR-active and ER-active PAHs were similar to those reported for other xenobiotics of concern. REP values presented here can be employed for assay-specific mass-balance (potency-balance) analysis and provide greater accuracy than could be achieved through the use of nonspecific literature values. A 10-h acid treatment followed by a nanopure water rinse was successful in degrading dioxinlike PAHs to non-AhR active products and should be a useful procedure for bioassay- 136 VILLENEUVE ET AL. TABLE III. Total 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) equivalents (TEQs) contributed by PAHs calculated for selected sections of a sediment core from Tokyo Bay, Japan,a using five sets of published relative potencies (REPs) for PAHs (relative to TCDD) Section (cm) 4–6 14–16 25–30 45–50 65–70 85–90 mean Clemonsb Hepa 1c1c7 Willettc H4IIE-wt Bolsd RTL-W1 Villeneuvee PLHC-1 Villeneuvef H4IIE-luc 3217 6220 3557 2375 749.3 181.8 2716 729.2 1650 1158 830.1 206.1 29.90 767.2 125.2 292.2 223.5 165.9 38.66 4.079 141.6 32.25 69.74 47.65 34.07 8.968 1.418 32.35 7.935 17.63 13.30 9.831 2.460 0.3076 8.577 Unit ⫽ pg TEQ/g sediment (dry wt). a Yamashita et al., 2000. b Clemons et al., 1998; luciferase induction in transiently transfected Hepa 1c1c7 cells. c Willett et al., 1997; EROD induction in wild-type H4IIE rat hepatoma cells. d Bols et al., 1999; EROD induction in wild-type RTL-W1 rainbow trout hepatoma cells. e This study; EROD induction in wild-type PLHC-1 Poeciliopsis lucida hepatoma cells. f This study; luciferase induction in stably transfected H4IIE-luc rat hepatoma cells. directed fractionation studies examining the relative contribution of PAHs and other acid-labile compounds to the total dioxinlike potency of environmental extracts. Overall, this research has contributed to a growing consensus regarding the dioxinlike potency of priority PAHs and PAH derivatives and has provided some additional evidence of potentially estrogenic PAHs. This work was supported by U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) Biology Exploratory Grants Program, grant no. R85371-01-0; cooperative agreement CR 822983-01-0 between Michigan State University and the U.S. EPA; and the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences Superfund Basic Research Program NIH-ES-04911. We thank Emily Nitsch for her technical assistance. We also acknowledge the support of colleagues from Michigan State University’s Aquatic Toxicology Laboratory. REFERENCES Basu N, Billiard S, Fragoso N, Omoike A, Tabash S, Brown S, Hodson P. 2001. Ethoxyresorufin-O-deethylase induction in trout exposed to mixtures of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Environ Toxicol Chem 20:1244 –1251. Behrens A, Schirmer K, Bols NC, Segner H. 2001. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons as inducers of cytochrome P4501A enzyme activity in the rainbow trout liver cell line RTL-W1, and in primary cultures of rainbow trout hepatocytes. Environ Toxicol Chem 20:632– 643. Blanchard M, Teil MJ, Carru AM, Ollivan D, Garban B, Chesterikoff A, Chevreuil M. 1999. PCB and PAH impacts on cytochrome P-450-dependent oxidases in roach (Rutilus rutilus) from the Seine River (France). Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 37:242–250. Bols NC, Schirmer K, Joyce EM, Dixon DG, Greenberg BM, Whyte JJ. 1999. Ability of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to induce 7-ethoxyresorufin-O-deethylase activity in a trout liver cell line. Ecotoxicol Environ Safety 44:118 –128. Brunström B, Broman D, Näf C. 1991. Toxicity and ERODinducing potency of 24 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in chick embryos. Arch Toxicol 65:485– 489. Clemons JH, Allan LM, Marvin CH, Wu Z, McCarry BE, Bryant DW, Zacharewski TR. 1998. Evidence of estrogen- and TCDDlike activities in crude and fractionated extracts of PM10 air particulate material using in vitro gene expression assays. Environ Sci Technol 32:1853–1860. Demirpence E, Duchesne MJ, Badia E, Gagne D, Pons M. 1993. MVLN cells: a bioluminescent MCF-7-derived cell line to study the modulation of estrogenic activity. J Steroid Biochem Molec Biol 46:355–364. Fent K, Bätscher R. 2000. Cytochrome P4501A induction potencies of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in a fish hepatoma cell line: Demonstration of additive interactions. Environ Toxicol Chem 19:2047–2058. Finney DJ. 1978. Statistical method in biological assay. London: Charles Griffin and Company. Gerhart EH, Carlson RM. 1978. Hepatic mixed function oxidase activity in rainbow trout exposed to several polycyclic aromatic compounds. Environ Res 17:284 –295. Hahn ME, Lamb TM, Schultz ME, Smolowitz RM, Stegeman JJ. 1993. Cytochrome P4501A induction and inhibition by 3,3’,4,4’-tetrachlorobiphenyl in an Ah receptor-containing fish hepatoma cell line (PLHC-1). Aquat Toxicol 26:185–208. Hahn ME, Woodward BL, Stegeman JJ, Kennedy SW. 1996. Rapid assessment of induced cytochrome P4501A (CYP1A) protein and catalytic activity in fish hepatoma cells grown in multi-well plates. Environ Toxicol Chem 15:582–591. Hightower LE, Renfro JL. 1988. Recent applications of fish cell culture to biomedical research. J Exp Zool 248:290 –302. Jung DKJ, Klaus T, Fent K. 2001. Cytochrome P450 induction by nitrated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, azaarenes, and bi- RELATIVE POTENCIES OF INDIVIDUAL PAHS nary mixtures in fish hepatoma cell line PLHC-1. Environ Toxicol Chem 20:149 –159. Khim JS, Kannan K, Villeneuve DL, Koh CH, Giesy JP. 1999c. Characterization and distribution of trace organic contaminants in sediment from Masan Bay, Korea. 1. Instrumental analysis. Environ Sci Technol 33:4199 – 4205. Khim JS, Lee KT, Kannan K, Villeneuve DL, Giesy JP, Koh CH. 2001b. Trace organic contaminants in sediment and water from Ulsan Bay and its vicinity, Korea. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 40:141–150. Khim JS, Lee KT, Villeneuve DL, Kannan K, Giesy JP, Koh CH. 2001. In vitro bioassay determination of dioxinlike and estrogenic activity in sediment and water from Ulsan Bay and its vicinity, Korea. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 40:151–160. Khim JS, Villeneuve DL, Kannan K, Koh CH, Giesy JP. 1999b. Characterization and distribution of trace organic contaminants in sediment from Masan Bay, Korea. 2. In vitro gene expression assays. Environ Sci Technol 33:4206 – 4211. Khim JS, Villeneuve DL, Kannan K, Lee KT, Snyder SA, Koh CH, Giesy JP. 1999. Alkylphenols, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and organochlorines in sediment from Lake Shihwa, Korea: Instrumental and bioanalytical characterization. Environ Toxicol Chem 18:2424 –2432. Koh CH, Khim JS, Lee KT, Villeneuve DL, Kannan K, Giesy JP. 2001. Occurrence and distribution of trace organic contaminants in environmental samples from Onsan Bay, Korea. Environ Sci Technol. Submitted. Pons M, Gagne D, Nicolas JC, Mehtali M. 1990. A new cellular model of response to estrogens: a bioluminescent test to characterize (anti)estrogen molecules. Biotechniques 9:450 – 459. Putzrath RM. 1997. Estimating relative potency for receptor-mediated toxicity: reevaluating the toxic equivalence factor (TEF) model. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 25:68 –78. Ryan JA, Hightower LE. 1994. Evaluation of heavy-metal ion toxicity in fish cells using a combined stress protein and cytotoxicity assay. Environ Toxicol Chem 13:1231–1240. Sanderson JT, Aarts JMMJG, Brouwer A, Froese KL, Denison MS, Giesy JP. 1996. Comparison of Ah receptor-mediated luciferase and ethoxyresorufin-O-deethylase induction in H4IIE cells: Implications for their use as bioanalytical tools for the 137 detection of polyhalogenated aromatic hydrocarbons. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 137:316 –325. Sanderson JT, Giesy JP. 1998. Wildlife toxicology, functional response assays. In: Meyers RA editor. Encyclopedia of environmental analysis and remediation. New York: John Wiley. p 5272–5297. Villeneuve DL, Blankenship AL, Giesy JP. 2000. Derivation and application of relative potency estimates based on in vitro bioassay results. Environ Toxicol Chem 19:2835–2843. Villeneuve DL, Kannan K, Khim JS, Falandysz J, Nikiforov VA, Blankenship AL, Giesy JP. 2000b. Relative potencies of individual polychlorinated naphthalenes to induce dioxinlike responses in fish and mammalian in vitro bioassays. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 39:273–281. Villeneuve DL, Blankenship AL, Giesy JP. 1998. Interactions between environmental xenobiotics and estrogen receptor-mediated responses. In: Denison MS, Helferich WG, editors. Toxicant-receptor interactions. Philadelphia: Taylor and Francis. p 69 –99. Villeneuve DL, DeVita WM, Crunkilton RL. 1998. Identification of cytochrome P4501A inducers in complex mixtures of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). In: Little EE, DeLonay AJ, Greenberg BM editors. Environmental toxicology and risk assessment. Volume 7. ASTM STP 1333. West Conshohocken, PA: American Society for Testing and Materials. Villeneuve DL, Khim JS, Kannan K, Giesy JP. 2001. In vitro response of fish and mammalian cells to complex mixtures of polychlorinated naphthalenes, polychlorinated biphenyls, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Aquat Toxicol 54:125–141. Willett KL, Gardinali PR, Sericano JL, Wade TL, Safe SH. 1997. Characterization of the H4IIE rat hepatoma cell bioassay for evaluation of environmental samples containing polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 32:442– 448. Yamashita N, Kannan K, Imagawa T, Villeneuve DL, Hashimoto S, Miyazaki A, Giesy JP. 2000. Vertical profile of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins, dibenzofurans, naphthalenes, biphenyls, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and alkylphenols in a sediment core from Tokyo Bay, Japan. Environ Sci Technol 34:3560 –3567.