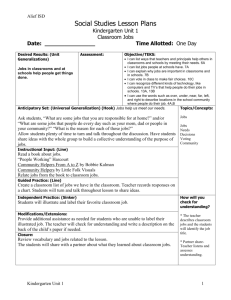

Schools Designed Community Participation

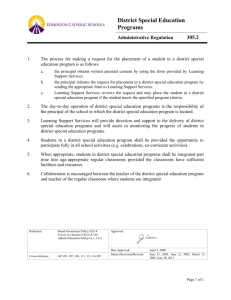

advertisement