Pathways to POLST Registry Development: Lessons Learned Dana M. Zive Terri A. Schmidt

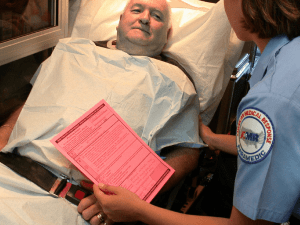

advertisement