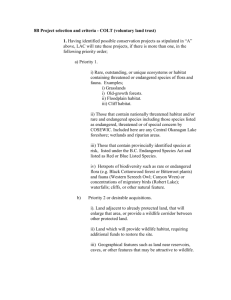

ACRP Report 122 Airport Toolbox for

advertisement