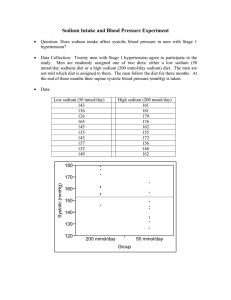

Sodium intake for adults and children

advertisement