Lighting the way ahead

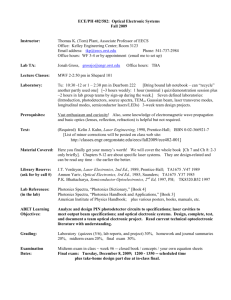

advertisement