In This Issue April 2005 Vol.3 No.3

April 2005 Vol.3 No.3

In This Issue

Some thoughts about the New

Learning Centre

A Shakespearean

Pedagogy: Teachers and Their

“Bit Parts”

The Bigger Picture:

Using a Photo File to

Support Student Learning

“Learning by Doing”: Active and Inquiry-Based Learning

Strategies in Science

“How Does Teaching

Inform Research?”:

A Whiteheadian Perspective

Steam, Sautee, and Fricassee:

Learning to Create and

Benefi t From Inclusive

Learning Environments

Spring Teaching Days

Professors, Graduate

Students, and Collaboration

Survey

Reflecting the Scholarship of

Teaching and Learning at the

University of Saskatchewan

Food for Thought from The GMTLC

Have you ever wondered what someone like Shakespeare thought about teaching? If you were educated in English schools, he probably had a part to play in your education. In this issue, our program coordinator Joel Deshaye discovers why teachers had “bit parts” in Shakespeare’s life.

In another article, Sandra Bassendowski from the College of Nursing shows how using images in a photo fi le can help students see the bigger picture. She argues that creative teaching methods will improve communication and help form new perspectives on course content.

Our program coordinator Kim West contributes to this issue, too, with an article on learning by doing. She offers a list of active and inquiry-based learning strategies for use in science courses - or in any courses where students will benefi t from applying their knowledge as they learn.

Another substantial part of this issue is from Adam Scarfe, a scholar in the

Process Philosophy Unit. He asks a rare question: how can teaching inform research? His answer, based on the philosophy of Whitehead and recent scholarship, uncovers a surprising reciprocity.

In an interview, our program coordinator Tereigh Ewert-Bauer talks with Deirdre

Bonnycastle from the Extension Division and the College of Medicine on how to put diversity into practice in the classroom. Read on; this one really cooks.

In keeping with our focus on graduate students, we also offer two interviews with winners of the Distinguished Supervisor Award on collaboration between professors and students. The interviews follow on the heels of the popular Best

Practices in Graduate Supervision conference on March 11, organized by Rob

Angove.

In other news, with this issue we say an early goodbye to Joel Deshaye, who is moving to Montréal in July to enroll in McGill University’s doctoral program in English Literature. To get a sense of the diffi culty in making such a decision, check his article on doctoral programs in our online Bridges from last

September: http://www.usask.ca/tlc/bridges_journal/v3n1_sep_04/v3n1_ pitfalls_promises.html.

The Gwenna Moss Teaching & Learning Centre

37 Murray Building • 966-2231

April 2005

Vol. 3 No. 3

The Gwenna Moss Teaching

& Learning Centre

University of Saskatchewan

Room 37 Murray Building

3 Campus Drive

Saskatoon, SK S7N 5A4

Phone (306) 966-2231

Fax (306) 966-2242 e-mail: corinne.f@usask.ca

Web site: www.usask.ca/tlc

Bridges is distributed to every teacher at the University of

Saskatchewan and to all the

Instructional Development Offices in Canada, and some beyond.

It is freely available on the world wide web through the

TLC web site. Your contributions to Bridges will reach a wide local, national, and international audience.

Please consider submitting an article or opinion piece to

Bridges . Contact any one of the following people; we’d be delighted to hear from you!

Walter Archer

Acting Director

Phone (306)966-5536

Walter.Archer@usask.ca

Christine Anderson Obach

Program Coordinator

Phone (306) 966-1950 christine.anderson@usask.ca

Joel Deshaye

Program Coordinator

(306) 966-2245 joel.deshaye@usask.ca

Corinne Fasthuber

Assistant

Phone (306) 966-2231 corinne.f@usask.ca

Views expressed in Bridges are those of the individual authors and are not neccesarily those of the staff at the GMTLC.

ISSN 1703-1222

S

OME THOUGHTS ABOUT THE

N

EW

L

EARNING

C

ENTRE

Walter Archer, Acting Director, GMTLC

I’m

sure that the readers of

Bridges are very interested in the New

Learning

Centre that is proposed in

A Framework for Action:

University of

Saskatchewan Integrated Plan 2003-

07 . As you may recall, that document states that the current Gwenna Moss

Teaching & Learning Centre will be central to the new entity. Other existing units that are candidates for inclusion in the New Learning Centre are the Centre for Distributed Learning, the Instructional Design Group, parts of

Extension Credit Studies, part or all of the Division of Media and Technology, components of Information Technology

Services, and components of the

Library.

The nature of the New Learning Centre will depend partly on the direction in which the University is guided by the foundational document on Teaching and Learning that is currently being created. As you probably know, in aid of shaping this foundational document the University has already sponsored presentations by a number of outside experts. The Integrated

Planning office has also organized a series of workshops through which all interested parties on campus can have input into the foundational document, now scheduled for completion and approval by about December, 2005.

difference is not trivial. A focus on teaching performance tends to put all the heat on the faculty member or other university teacher. We make the more or less tacit assumption that if the teacher performs well, the students will learn well – and, presumably, will reward the teacher with a good rating on the end of term evaluation form.

A focus on learning outcomes, on the other hand, spreads the responsibility for learning more broadly. The teacher, the institution, and the student all have an active role. The institution has a responsibility to not only provide instructors, but also to facilitate student learning by providing information resources (library, access to the Internet) and a physical environment (labs, classrooms, bookstore, etc.) conducive to learning. Given this environment, the student has an opportunity to engage in self-directed learning – i.e., to take a pro-active approach that may (or may not) dispense partly or entirely with the assistance of a teacher. In the sub-field of adult education self-directed learning is much more common than it is in regular undergraduate education, probably because the learners are older, have more life experience to draw upon, and tend to be much more assertive in general. Not surprisingly, the substantial literature on selfdirected learning is mainly focused on adult learners. However, a more assertive, pro-active role for regular undergraduate students is also possible

– if the institution decides to focus on learning outcomes with teaching being an important means of fostering learning but not the only one.

One basic issue which the foundational document will have to address is whether we should focus our attention primarily on learning outcomes, or primarily on teacher performance. The

2

Which direction the foundational document takes on this issue will affect how the New Learning Centre is put together. Like analogous centres at most other institutions, the current

Gwenna Moss Teaching & Learning

Centre is actually a teaching centre.

It helps teachers (including graduate teaching assistants) to diversify and strengthen their teaching. It does not deal directly with students as learners.

The University of Saskatchewan does provide learning support services, but with the exception of the OWL (Online

Writing Lab) these are not housed in the GMTLC.

A few institutions do group teaching support and learning support within one unit. Michael Ridley, in his

January presentation at this university, described such an arrangement within the Learning Commons at his own institution, the University of Guelph. I visited their Learning

Commons recently, but unfortunately it was during spring break so I did not observe the beehive of activity that he described. However, this example, and a similar one recently created at

Dalhousie University, at least illustrate the feasibility of trying for synergy between teaching support and learning support by co-locating them, with or without putting them within the same administrative unit.

Such a co-location arrangement within our New Learning Centre might have the disadvantage, however, of faculty tending to avoid the Centre for fear of encountering their own students there, and thereby exposing their own need for teaching support. This is certainly a possibility to be considered. One very experienced director of a teaching and learning centre told me that at his institution (McMaster) the presence of students in the TLC would have deterred faculty from making use of the TLC a couple of decades ago, but not now. A general universitywide focus on learning outcomes, in which student and teacher are clearly working together toward the same goal, might tend to mitigate this danger. However, this is a matter to be investigated further if we were to consider grouping both teaching support and learning support within our New Learning Centre.

Another matter that will be addressed by the Teaching & Learning foundational document is the integration of learning technologies into the overall process of teaching and learning at this institution. Whatever is stated on this topic may also have implications for the role and structure of our New

Learning Centre. The Framework for

Action document has suggested that existing units that tend to be associated with learning technologies will be included within the new entity. This is consistent with the structure at many institutions (e.g., Waterloo) where at least one substantial sub-unit within the overall teaching and learning support unit is focused on learning technologies.

However, we should be careful to avoid what happened at at least one other institution, where the entire teaching and learning centre came to be so not focused on any particular teaching methodology, evolved to serve the rest of the campus. There is apparently a useful collaborative relationship between the two units.

A somewhat similar situation already exists at the University of

Saskatchewan, where the GMTLC has been created to serve the institution as a whole but some of the colleges have developed their own units to support their more specialized teaching functions. Presumably a useful collaborative relationship can be maintained when the GMTLC becomes the core of the New

Learning Centre. At the University of Calgary, the strategic plan of the

Learning Commons proposes just such a structure, in which the central unit would provide general support

ONE basic issue which the foundational document will have to address is whether we should focus our attention primarily on learning outcomes, or primarily on teacher performance. The difference is not trivial.

closely associated with technology that teachers not particularly interested in technology began to avoid the TLC.

One issue that will affect the New

Learning Centre but which may or may not be addressed in the foundational document is the matter of centralization or decentralization of teaching and learning support. McMaster University is an interesting example of a partly decentralized model. At that institution there is one TLC for the Health

Sciences faculty and one for the rest of the campus. This situation apparently arose after McMaster became worldrenowned for developing case-based teaching in its Faculty of Medicine.

They were soon deluged with visitors wanting to learn this method, and the health sciences TLC evolved from their need to deliver this instruction to visitors and their own teaching staff.

Meanwhile, a more broadly based TLC, for teaching while some or all of the faculties would create structures to support the more specialized teaching techniques used in those faculties.

Finally, I’d like to mention briefly the research function that the Framework for Action proposes for the New

Learning Centre. A number of TLCs at Canadian universities have such a research function – some more explicit than others, some located within the

TLC and some located outside the TLC but closely associated with it. One example of the former is the Learning

Commons at the University of Calgary, which conducts and disseminates a substantial amount of research related to teaching and learning, particularly technology mediated teaching. One interesting example of a related unit located outside the TLC is the

Programme for Educational Research and Development (PERD) at McMaster,

3

which specializes in research related to the type of teaching done in the Faculty of Health Sciences, within which PERD is housed. The

University of Saskatchewan may not have a specialty as well known as case-based teaching in Health

Sciences at McMaster, but it does have considerable renown in distributed learning, a necessity for an institution with a mandate to deliver courses throughout an entire province. Therefore, it is appropriate that the Centre for Distributed

Learning should carry on its research as a sub-unit within the New Learning

Centre, as is suggested in the

Framework for Action .

These are some of my thoughts about the New Learning Centre. It should be stressed that these are my thoughts, and do not necessarily correspond to the opinions of the Instructional

Development Committee of Council, the Integrated Planning Office, or any of the other committees and groups involved with the Teaching and

Learning Foundational Document and the development of the New Learning

Centre.

I hope that many of you will contribute your own thoughts during the consultation process that will be taking place over the coming months.

A Shakespearean

Pedagogy:

Teachers and Their

“Bit Parts”

By Joel Deshaye,

Department of English & GMTLC

For

Shakespeare, far too many teachers have habits of speaking convolutedly, using jargon flippantly, following vain digressions, stressing obscure theories, performing self-indulgently, and masking their errors. He identifies these negative practices in most of only six characters in his plays who are explicitly considered teachers (Winson par. 2, 5-7,

11-2). Patricia Winson (1997) identifies the two who have significant roles: Holofernes, the schoolmaster from Love’s

Labour’s Lost (1594-5) and

Prospero, the magician from

The Tempest (1606), one of

Shakespeare’s final plays.

All the others have what

Winson calls “bit parts” (par.

5) whose insignificance is a telling feature of Shakespeare’s opinion of them. Prospero is the only one to reject the pedantry that marks these characters as less interested in student learning and more interested in pedagogical performance.

Of this pair, Holofernes is the prototypical pedant; in fact, Shakespeare coined the word to describe him (Winson par. 7). The Oxford English Dictionary describes a pedant as a schoolmaster, but also as a person who values theoretical trifles over practical application, “a doctrinaire.” Winson applies these characteristics to Holofernes, “a hypocrite or false prophet [... who] uses his learning and verbal skills to obfuscate and distort reality” (par. 7). He also uses many “hard [Latin-origin] words” — as do many professors in the Humanities

(Winson par. 11). Yet, his efforts to name simple things fail through circular references. Real life — a world, foremost, of things — he cannot describe.

It is not the answer that enlightens, but the question.

Eugene Ionesco,

Decouvertes,1969

?

For all his high artistry, Shakespeare was not above lampooning his own society, especially when he noticed hypocrisy like in the case of Holofernes. When

Shakespeare enrolled in school as a boy of six years old, the government of

Elizabeth I had recently finished codifying the expectations for teachers: they had to promote Christian virtues and avoid the opposite (Winson par. 14). In contrast,

Winson observes that the name Holofernes has a “diabolical [...] infernal suffix”

(par. 15).

Moreover, she notes that two of Shakespeare’s most famous speeches allude to teaching in the worst ways: in one, Macbeth speculates that his assassination plot might backfire because of the dangers of “teach[ing] / Bloody instructions, which, being taught, return / To plague th’ inventor” ( Macbeth V. vii. 8-10). In the other, Shylock justifies his merciless demands, asking, “[i]f a Jew wrong a

Christian, what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge. The villainy you teach me,

I will execute, and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction” ( Merchant III . i.

4

68-73). These contexts are brutal and deadly, prompting speculation about whether Shakespeare’s schooling might have elicited such hellish imagery in connection with teaching.

Years later and shortly before his retirement from the theatre, Shakespeare wrote The Tempest , which led 19th

C. critics to think of Prospero as an autobiographical character (Smith 1609). Shakespeare characterizes

Prospero as a dignified scholar of the “liberal arts” (I. ii.

73) and magician who eventually retires his enchanted cloak and staff so that he can return from his exile. James

(1967) shows that Prospero’s scholarship in the liberal arts is a product of his life in Milan. James also contends that when he calls his magic his art, he is not confusing his skills as a scholar with the skills of a magician (62-5).

His wizardry is part of the island of his exile, and will stay there when he leaves.

At first, an audience of attentive teachers might see The

Tempest as a play about wizardry and teaching. For instance, Prospero developed his magical powers while in exile, coincidentally with the habit, honed in twelve years of near-solitude, of talking at length. Moreover, like many teachers, he has the magical ability to put people to sleep simply by talking (e.g. I. ii. 185-7). And he is constantly lecturing his companions about how they are subordinate to his power.

Prospero developed his magical powers while in exile, coincidentally with the habit, honed in twelve years of near-solitude, of talking at length.

Moreover, like many teachers, he has the magical ability to put people to sleep simply by talking

...

However, there is reason to believe that Prospero plans to leave his autocratic tendencies on the island. He seems to develop a new way of teaching that will come with him when he returns to his home in Milan. Although he treats some characters in the play with surly, pedantic condescension, he treats his daughter Miranda with considerably more sensitivity and respect, letting her questions guide his lectures. He seems to encourage her to embody the name he (presumably) had a role in giving her: Miranda is a name that derives from the Latin term for wonder . To show his willingness to listen, he removes his magical cloak when he teaches her about their past, but he conspicuously calls himself her “schoolmaster” (I. ii.

172) as soon as he wears his cloak again, reinforcing the connection between teaching and his manipulative magic.

Although he occasionally chides her when he suspects

(incorrectly) that Miranda is not listening to him, he reserves his harsh lectures for the enchanted spirit Ariel, who promises to do Prospero’s bidding in exchange for

5 freedom. He constantly threatens Ariel and others with his

“art” — his magic. With them as opposed to with Miranda, he invokes his power often. To impress others, he will

“[b]estow upon [their] eyes [...] / Some vanity of [his] art,” saying, “[t]hey expect it from me” (IV. i. 40-2). They expect a performance, a dazzling show of his wit and power. He charms them, capturing his enemies by jostling their senses

(V. i. 158). His magic certainly does not teach them any lessons, only confusion and resentment.

Eventually, Prospero decides he will break the spell that imprisons and crazes his enemies, promising to stop using his “rough magic” (V. i. 50) and to instead break his magic staff and drown his book of spells in deep water (V. i. 50-

7). He renounces his magic, his art of teaching by lecture or performance. Speaking plainly (by Shakespearean standards) at last, he leads them to think for themselves and dispel the illusions of the enchanted island:

The charm dissolves [...],

And as the morning steals upon the night,

Melting the darkness, so their rising senses

Begin to chase the ignorant fumes that mantle

Their clearer reason. (V. i. 64-8)

Instead of controlling their ignorance, he begins to appeal to their reason.

Freeing his enemies from his charms gives them respect and feelings of gratitude for him. Knowing he can return home from his exile, he seems humbled by having to leave his magic on the island. Prospero’s epilogue, when all other characters have left the stage, seems to be directed at the audience members, whom he asks to draw near.

Now my charms are all o’erthrown,

And what strength I have’s mine own,

Which is most faint. Now ’tis true,

I must be here confin’d by you,

[...] by your spell. (1-8)

We are his students, and he has given us the power.

Prospero shows that productive teaching is not magic.

Anyone can learn how. To teach well, Shakespeare suggests, people should speak plainly, show humility, care for others

(as Prospero does with his daughter) and see themselves not as figures of exclusive power. Furthermore, they should be willing to learn, too. As seen in his forgiveness of his enemies

(V. i. 25-30), Prospero “seems to undergo a kind of spiritual education during the play which an absolute power could not undergo” (Smith 1608).

A brief example from another play will reinforce the importance of teachers who continue to learn. In

Shakespeare’s play Henry IV, Part One , Sir Richard Vernon tells the impetuous rebel Hotspur that the new King Henry has offered to avoid a bloody war by resolving the rebellion in

single combat, Henry against Hotspur.

Consistent with his splenetic and vain temperament, Hotspur demands whether Henry intended the challenge to mock him. Vernon explains that, to the contrary, Henry’s modesty was wise and self-deprecating and that he chided

“his truant youth with such a grace / As if he mast’red there a double spirit / Of teaching and of learning instantly”

(V. ii. 62-4).

James, D. G. The Dream of Prospero.

Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967.

Oxford English Dictionary Online.

Oxford. Accessed March 14, 2005.

<http://www.oed.com>

Shakespeare, William. 1 Henry IV.

The Riverside Shakespeare. Boston:

Houghton Mifflin Co., 1974. 842-85.

Hotspur refuses to believe Vernon, and rushes to war. In this scene,

Shakespeare offers a glimpse of what teaching and learning mean. On one hand, he shows how Hotspur holds to his own presuppositions about

Henry’s character, refusing to change his views despite evidence that they could be incorrect; his stubborn refusal is like how we sometimes cling to our paradigms, epistemologies, ways of thinking, despite realizing that our views are uncertain and imperfect.

Hotspur is unwilling to learn.

On the other hand, Henry seems to see beyond his pride. In Vernon’s view, at least, Henry is willing to criticize the indiscretions of his own wild youth, hoping that he can save his people from an unnecessary war. His willingness to reflect on himself earns him mastery (at least for the moment), of two different activities: teaching and learning. They merge in his process of analysis and self-reflection. Similarly, in The Tempest , Prospero has the time to think and learn new skills and philosophies (and maybe this justifies academic sabbaticals).

References

———————.

Riverside Shakespeare

Houghton Mifflin Co., 1974. 1306-

1342.

———————.

Smith, Hallet. “The Tempest.” The

Riverside Shakespeare . Boston:

Houghton Mifflin Co., 1974. 1606-10.

Winson, Patricia. “‘A Double Spirit of Teaching’: What Shakespeare’s

Teachers Teach Us.” Early Modern

Literary Studies. Special Issue 1 (1997):

8.1-31. Accessed March 14, 2005.

<http://purl.oclc.org/emls/si-01/si-

01winson.html>

Macbeth. The

. Boston:

Venice. The Riverside Shakespeare.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1974.

250-285.

———————.

1638.

The Merchant of

The Tempest. The

Riverside Shakespeare . Boston:

Houghton Mifflin Co., 1974. 1606-

F I N I S.

Prospero becomes a teacher-scholar who, unlike Holofernes, has scholarship to support his teaching. Although his discipline is the liberal arts (which proves capable of mending conflict and promoting education), teacher-scholars in any discipline could learn from him. Shakespeare shows that teacherscholars can have more than “bit parts” in the lives of others. To get a leading role, they only need to stop performing as pedants.

Forgetting important dates?

We know how to help.

The

GMTLC woud be happy to give you a 2005 sticky calendar.

Drop by the Centre and pick one up, or call us at 2231 and we will mail one to you.

6

T

HE

B

IGGER

P

ICTURE

:

Using a Photo File to Support Student Learning

By Sandra Bassendowski,

College of Nursing

We

experience many images in our daily lives, such as those on television, movies, Internet, books, magazines, performance arts, and other visual productions (Heise, 2004,

1). These images have a profound impact on students’ lives, their style of communication, and their approach to learning. From a teaching and learning perspective, how can educators present course content in a way that connects with learners, their learning styles, and their approach to the visual culture?

Creative instructional strategies provide opportunities for students to participate in meaning-making for their own learning and personal experience. I developed The Bigger

Picture instructional strategy with the expectation that it would effectively engage students in course content.

Supporting Theory

The literature reveals that creative instructional strategies support student learning and involvement in learning

(Bustle, 2004; Chambers et al.,

2000; Grant Kalischuck & Thorpe,

2002; Hamza, Khalid, & Farrow,

2000; Heise, 2004; Leggo, 2003;

Lones, 1999; Jackson, 2003). Dewulf and Baillie (as cited in Jackson,

2003) describe creativity as ‘shared imaginations’. They suggest that it involves students having their own imagination and then sharing it with others. The creativity comes alive through teaching processes and interactions (Jackson, 2003; Jungst,

Licklider, & Wiersema, 2003).

“Adult educators seeking to foster transformative learning invoke the role of imagination in developing new perspectives; they view the arts as a way of engaging adults in imaginative exploration of themselves and their relationship to the world” (Kerka,

2002,1).

STUDENTS have been positive about the instructional strategy; their feedback suggests that the activity gives them a chance to analyze course content in a new way.

a picture or image that represents meaning for them as a response to a specific question, scenario, or situation that is related to course content. The activity can focus on concepts, ideas, questions, case situations, or situations.

For example, in one of my courses, I asked students to think about the content of a specific chapter in a text and choose a picture that illustrated their feelings or thoughts about something that they read in the chapter. Students are free to view all pictures for about

10 minutes. Once everyone has chosen a picture they volunteer to present it to the class and discuss why the picture represents their thinking and how it relates to evidence or content from the course.

The use of pictures and images may appeal more to the visual learners in a class but it also has a positive effect on students who are used to listening to lectures or responding to written assignments (Stanford, 2003). Students can find a rich source of meaningful learning opportunities through the arts and, as a result, develop new ways of seeing, knowing, and experiencing

(Anonymous, 2000; Hedden, 2003;

Kerka, 2002). The Bigger Picture activity creates an opportunity for students to show evidence of learning as it supports a shift in viewpoints and perspectives. This shift in thinking involves a re-organization of existing concepts and a rethinking of established patterns (Chaska, 1990).

For example, in one of my courses, a student chose a page-sized picture of an ‘eye’ in response to a question related to nursing issues. She explained that, for her, the picture of the eye represented the silence that has occurred throughout most of nursing’s history. Nurses saw what happened but rarely spoke out on issues. She commented on a Canadian school of nursing that once had the motto, ‘I see and am silent.’ She then proceeded to link her views on the picture to content in the course text about the need to be a voice of agency.

Development of The Bigger

Picture Strategy

Pictures, photos, drawings, artwork, and graphics can be used in this instructional strategy. I have been collecting pictures and images for more than 10 years and I look for ones that represent diverse situations and settings, are visually interesting, and can be interpreted in a variety of ways.

At the start of the activity, I lay out all the photos and pictures on a large table that is accessible for viewing from both sides.

Students are given instructions to choose

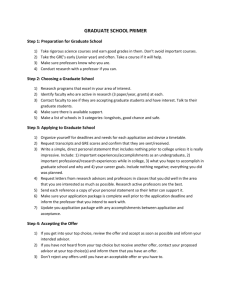

In another course, a student chose the drawing (Figure 1) that portrays a dance done by the Ngöbe-Buglé people of Panama. She stated that from her perspective the art piece depicted

Brookfield’s (1995) description of critical reflection as a matter of ‘stance and dance’. She liked the flexible formation of the dancers and suggested that for her it illustrated the concept of critical reflection as always being open to a change in direction or movement.

7

skills and promotes the formation of new perspectives about learning and course content. The use of pictures, paintings, graphics, and photos in The

Bigger Picture instructional strategy supports student learning from the perspective of ‘shared imaginations’.

Heise, D. (2004). Is visual culture becoming our canon of art? [Electronic version]. Art Education , 57(5), 41-47.

Jackson, N. (2003). Creativity in higher education . Retrieved February 28,

2005, from http:// www.heacademy.ac.uk/853.htm

References

Anonymous. (2000). Arts and learning:

An integrated approach to teaching and learning in multicultural and multilingual settings [Electronic version].

Harvard Educational Review , 70(1),

128-130.

Figure 1. Drawing depicting a dance of the Ngöbe-Buglé people of Panama

“Adapt not Adopt”

Technique

Although I initially developed this strategy for an adult education course, it can be adapted to a variety of content within other courses. The strategy takes about one hour to complete depending on class size. It is best used with small groups due to the time required for each student to share their thoughts and engage other students in discussion about the pictures. With larger groups,

I have used the strategy with students presenting in pairs or groups of three.

The strategy can be used at any time during the course.

Brookfield, S. (1995). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. San

Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bustle, L. (2004). The role of visual representation in the assessment of learning [Electronic version]. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 47(5),

416-424.

Chambers, A., Bartle Angus, J., Carter-

Wells, J., Bagwell, J., Greenbaum, J.,

Padget, D., & Thomson, C. (2000).

Creative and active strategies to promote critical thinking. Yearbook

(Claremont Reading Conference), 58-

69.

Chaska, N. (Ed.). (1990). The nursing profession: Turning points . Philadelphia,

PA: Mosby Company.

Summary

The activity, The Bigger Picture, challenges students to think about course content and describe how the picture or image that they have chosen portrays an aspect of the course. They determine the importance of concepts and learning outcomes for themselves rather than rely on someone else’s experience or on the memorization of facts and information. For students, the important part of the activity is that they actively participate in meaning-making for their own learning. Students have been positive about the instructional strategy; their feedback suggests that the activity gives them a chance to analyze course content in a new way.

The use of creative instructional strategies enhances communication

Grant Kalischuck, R., & Thorpe, K.

(2002). Thinking creatively: From nursing education to practice. The

Journal of Continuing Education in

Nursing, 33(4), 155-163.

Hamza, M., Khalid, M., & Farrow,

V. (2000). Fostering creativity and problem solving in the classroom.

Kappa Delta Pi , 37(1), 33-35.

Hedden, (2003). A qualitative study of university visual arts courses: An investigation of the instructional methods and attitudes of visual arts teachers.

Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Southern Illinois University at Carbondale.

Jungst, S., Licklider, B., & Wiersema,

J. (2003). Providing support for faculty who wish to shift to a learning-centered paradigm in their higher education classrooms. The Journal of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning . Retrieved

April 26, 2004, from http://titans.iusb.

edu/josotl/contents_v3_n3.htm

Kerka, S. (2002). Adult learning in and through the arts. ERIC Digest . Retrieved

February 28, 2005, from www.eric.

ed.gov

Leggo, C. (2003). Calling the muses:

A poet’s ruminations on creativity in the classroom. Education Canada , 43(4),

12-15.

Lones, P. (1999). Learning as creativity:

Implications for adult learners. Adult

Learning, 11(4), 9-12.

Stanford, P. (2003). Multiple intelligences for every classroom.

Intervention in School and Clinic , 39(2),

80-85.

“

Learning proceeds in fits and starts. Sometimes it moves forward rapidly with great insights.

Often it stalls, and learners believe nothing is happening and become frustrated. ... For many, learning is a spiral, where important themes are visited again and again throughout life, each time at a deeper, more penetrating level.

Teaching From the Heart , by Jerold W. Aps, 1996.

“

8

“

L

EARNING BY

D

OING

”: A

CTIVE AND

I

NQUIRY

-B

ASED

L

EARNING

S

TRATEGIES IN

S

CIENCE

by Kim West,

GMTLC

WHEN students start thinking about the importance and relevance of science and its impact on society, the learning benefits are amazing.

“To teach is to engage students in learning.”

- Education for Judgement: The Artistry of

Discussion Leadership by C.R. Christensen,

D.A. Garvin, and A. Sweet - 1991

In

the traditional approach to teaching science, the professor lectures and the students listen. In these classes, science is taught from the point of view of the expert (the teacher), emphasis is placed on content rather than learning, and the students have little to no responsibility for their own learning. Most professors who teach using a traditional approach argue that they need to lecture in order to cover course content, that students need to learn the basic concepts of science

(i.e. knowledge is cumulative), and that science has been successfully taught this way for many decades.

In recent years, some educators have advocated the use of active and inquiry-based strategies in science teaching, promoting engagement in learning. In active and inquiry-based approaches, the role of the teacher shifts from expert to facilitator and students are expected to become active learners. The philosophy behind both strategies is that students “learn best by doing, not by watching or listening”

(Felder & Brent 1999). Active learning incorporates strategies that require students to participate directly in their learning - to apply newly acquired knowledge to solve problems, to question and test theories, brainstorm, solve problems, hypothesize, summarize, or to critically think and interact with colleagues (Felder & Brent

1999; Hannula 2003; McConnell,

Steer, & Owens 2003). Inquirybased learning is a more specific term applied to learning situations where elements of scientific inquiry have been incorporated into active learning exercises (McConnell, Steer, & Owens

2003).

The Best of Both Worlds

Many professors who use inquirybased techniques suggest that students learn best in the sciences when they invest a part of themselves in their learning. Therefore, classes which emphasize the scientific method by teaching students to question theories and develop hypotheses are effective because they engage students in the process of learning (Hannula 2003).

Many studies have linked the use of active and inquiry-based learning to increased motivation in the classroom, improved student retention, increased concentration, better student-faculty interaction, enriched understanding of content, better feedback, and more supportive learning communities

(Felder & Brent 1996; Smith et al.

2005).

On the other hand, active or inquirybased exercises are time-consuming in terms of preparation time for the instructor and time spent in the classroom. In science, knowledge is

9 indeed cumulative, and students need to learn basic concepts before progressing further in their studies. Should science teachers maintain a focus on content, or incorporate active and inquiry-based strategies in their teaching? Can they successfully do both?

I would argue that the answer to this question is different for each teacher.

The question is rooted in our individual approaches to teaching, in our philosophy, and in our goals (Felder &

Brent 1999). If you believe active or inquiry-based learning compromises your content or curriculum, then these are techniques you probably shouldn’t be using (Felder & Brent 1999). If, on the other hand, your goals include promoting engagement or discovery, then active and inquiry-based learning may be extremely helpful in reaching those goals in the classroom. It doesn’t come down to having to make a choice

- many successful teachers build the best of both worlds by incorporating smaller components of active and inquirybased learning in their lectures without compromising course material.

Incorporating Active &

Inquiry-Based Learning

Strategies in Your Teaching

Implementing active or inquiry-based learning in your teaching can be as simple as stopping your lecture for a few minutes to ask students questions about the content you are teaching, breaking out into small discussion groups, and/or engaging students in interactive demonstrations. Here are a few simple techniques to try:

• Instead of asking “Any questions?,” stop and ask students to define concepts or ideas in their own words throughout your lecture (Felder 1994). Ask your students specific open-ended questions structured to provoke curiosity, relate

concepts to the real world, illustrate meaning, or trigger discussions and/or debate.

• Show rather than tell. Use interactive demonstrations and simulations to illustrate concepts and theories. Take this one step further and ask your students to predict behaviour and construct their own hypotheses before carrying out experiments or doing calculations. One way of doing this is to show your students a photograph, map, or diagram and ask them to make their own observations and interpretations (McConnell,

Steer, & Owens 2003).

• When lecturing, encourage students (particularly first-years)

The philosophy behind both strategies is that students

“learn best by doing, not by watching or listening”

(Felder &

Brent 1999).

to question concepts, ideas, and theories. Use examples from your own research to illustrate how the scientific process is carried out.

• Use case studies to illustrate contentious issues in science, such as genetically modified foods, or toxic waste disposal. When students start thinking about the importance and relevance of science and its impact on society, the learning benefits are amazing.

• Integrate current events into your lecture. For example, if you’re teaching geology, how could you not talk about the tsunami that recently hit South Asia?

• Incorporate active learning exercises such as conceptests and Venn diagrams into your teaching (McConnell, Steer,

& Owens 2003). Conceptests are short multiple-choice tests that faculty intersperse in their lecture to assess whether students are learning. Venn diagrams add a visual (graphical) touch when comparing and contrasting characteristics (mathematical sets) and demonstrating relationships between phenomena (hurricanes vs tornadoes; igneous vs sedimentary vs metamorphic rocks; vertebrates vs invertebrates)

(McConnell, Steer, & Owens 2003).

• Use concept maps to establish relevance and demonstrate how concepts are related to 1) one another;

2) the real world; and 3) other concepts in related scientific disciplines.

• Implement problem-based and cooperative learning in the field or lab.

Problem-based learning involves incorporating exercises in which students work individually or together in teams to pose and/or solve problems related to specific scenarios or topics.

Cooperative learning establishes community, better student-faculty interaction, and a more supportive and caring learning environment.

References

Christensen, C.R., Garvin, D.A., and Sweet, A. 1991. Education for judgement: The artistry of discussion leadership . Cambridge, Mass:

Harvard Business School.

Felder, R.M. 1994. Any questions?

Chemical Engineering Education,

28(3): 174-175.

Felder, R.M. and Brent, R. 1999.

FAQs. II. (a) Active learning vs covering the syllabus; (b) Dealing with large classes. Chemical

Engineering Education, 33(4): 276-

277.

Hannula, K.A. 2003. Revising geology labs to explicitly use the scientific method. Journal of

Geoscience Education, 51(2): 194-

201.

McConnell, D.A., Steer, D.N., &

Owens, K.D. 2003. Assessment and active learning strategies for introductory geology courses .

Journal of Geoscience Education,

51(2): 205-217.

Smith, K.A., Sheppard, S.D.,

Johnson, D.W., and Johnson, R.T.

2005. Pedagogies of engagement:

Classroom-based practices . Journal of Engineering Education, 94(1):

87-101.

10

“

H

OW

D

OES

T

EACHING

I

NFORM

R

ESEARCH

?:

”

A W

HITEHEADIAN

P

ERSPECTIVE

By Adam Scarfe, College of Education

In

conjunction with the

Gwenna Moss Centre’s endeavour to foster an emphasis on the Scholarship of Teaching, this article examines some of the interconnections between teaching and research. Particularly, I ask the question: how does teaching inform research? While an emphasis on the notion that research informs teaching is an overwhelmingly widespread phenomenon, there has been relatively little investigation of the possibility that teaching informs research. According to Becker and

Kennedy (2004), in almost all of the scholarly literature on the subject, the relationship between teaching and research is posited “all in terms of research enhancing teaching, ignoring any possible causality in the other direction” (1). However, here, I show how Alfred North Whitehead’s (1861-

1947) philosophy of education helps to answer the question as to how teaching informs research.

Alfred North Whitehead was a pre-eminent British Mathematician,

Philosopher, and Philosopher of

Education of the 20 th Century who taught at Harvard from 1924 to 1939.

His book, The Aims of Education , and especially the 1927-28 address,

“Universities and their Function,” responds directly to the question of how teaching informs research. He writes,

The justification for a university is that it preserves the connection between knowledge and the zest for life, by uniting (students) and

(professors) in the imaginative

(

( consideration of learning. (…)

(The) atmosphere of excitement, arising from the imaginative consideration of learning, transforms knowledge. A fact is no longer a fact: it is invested with all its possibility (93).

By the “imaginative consideration of learning,” Whitehead means the assessment not only of what in actuality, for example, of fact established by past research, but of students are in their prime, while professors are ‘experienced’ in terms of their research. A university performs its function by bringing students and professors together, thus “weld(ing) together imagination and experience”

Aims , 93).

is also the consideration of alternative possibilities or what might be , namely, creative potentialities for knowledge, research, learning, and self-realization. The premise here is that the consideration of novel possibilities for knowledge is the product of the imagination. For the imagination points to “the creation of the future”

Aims , 171). Hence, Whitehead is here making the point that for the most part, the imaginative capacities

It is by way of the fusion of experience and imagination which occurs in the interaction of teachers and students that new knowledge is created and transformed. In short, for Whitehead, teaching is not merely the imparting or the transference of the knowledge

-contents of research onto students.

The very assumption that it does echoes the ‘banking model’ of education much criticized by Paulo Freire, in which teachers consider themselves to be

‘depositors’ of information and expect students to be passive ‘depositories’ memorizing this information. Rather,

Whitehead makes the case that by interacting with teachers, students contribute to the process by which knowledge is created and transformed.

Not only that, but they teach teachers how to be imaginative and creative in their research. In order to clarify how this is the case, Whitehead writes,

(

Do you want your teachers to be imaginative? Then encourage them to research. Do you want your researchers to be imaginative? Then bring them into intellectual sympathy with

(students who are) at the most eager, imaginative period of life, when intellects are just entering upon their mature discipline.

Make your researchers themselves explain

to active minds, plastic and with the world before them; make your (…) students crown their period of intellectual acquisition by some contact with minds gifted with the experience of intellectual adventure (by which he means ‘research’)

Aims , 97).

explain ourselves, especially to students, requires us to connect the knowledge of our disciplines and our research with, and apply it to life. Most importantly is that through our interactions with students, teaching keeps knowledge fresh and alive.

According to Whitehead, “knowledge does not keep any better than fish”

( Aims , 98), meaning that knowledge, even that derived from our research, is continually in danger of becoming

‘inert’, irrelevant, outmoded, stale, rotten, or even dead. Students, for whom imagination is at its prime, inject possibility into existing knowledge, thereby “preventing it from becoming inert” ( Aims , 5). Through their learning and class work, students assist in the analysis, criticism, and synthesis of concepts, as well as in the creation and transformation of knowledge, by utilizing it, testing it, and “throwing it into fresh combinations” ( Aims , 1).

Therefore, for Whitehead, students and teachers ‘grow together’ and learn from one another, a process that not only contributes to, but constitutes research.

RATHER, Whitehead makes the case that by interacting with teachers, students contribute to the process by which knowledge is created and transformed. Not only that, but they teach teachers how to be imaginative and creative in their research.

These Whiteheadian conclusions about how teaching informs research are loosely supported by Becker and

Kennedy’s (2004) recent study, in which faculty members in Economics were interviewed and surveyed in respect to the question as to how their teaching informs their research. And, there was a consensus of responses to the effect that teaching substantially informs research. One professor stated that teaching Therefore, through teaching, the challenge to explain ourselves to students leads us to reconsider the basic presuppositions of our disciplines, as well as leading to further inquiry and research. The requirement to explain , whether it comes in the form of teaching, or in responding to criticisms of our research made by our scholarly peers, is the “motive power in the advance of thought” ( Essays ,

87). The challenge to explain is that which forces us to support our claims with reasons and to establish new connections between our concepts and investigations. Also, the challenge to

Stimulates ideas for research.

Whenever you have to explain something to someone, (…) you have to think it through more thoroughly than you otherwise would. (It) (…) reveals holes in one’s understanding, (and) (…) gives us ideas for research (Becker and Kennedy, 2).

Another professor stated that “Teaching keeps research in perspective – I can think of several instances in which teaching has forced me to come to my

11

senses and give up on a topic because

I couldn’t explain why it is important”

(9). Still others asserted that:

“Some of my best research definitely grew out of teaching the area and having to think about how to present ideas to students in as clean and simple a way as possible” (3).

“The best way to learn something is to attempt to teach it to others” (4).

“There are a number of occasions when my teaching lead to research, particularly when I made statements to my class, confident of my assertion, only to discover that it did not hold up (to scrutiny), and needed full rethinking” (6).

“Students (are part) of a team effort, helping me to work out my own ideas as these develop” (6).

“Questions from students, both shrewd and ignorant, have led to substantive research” (6).

“A bright student protested that the explanation seemed selfcontradictory. On reflection, I tended to agree” (7).

“Every hour spent interacting with students in the classroom makes me rethink my current research” (10).

References:

Becker, W. E. and Kennedy, P. E. (2004), “Does Teaching Enhance Research in

Economics?”: http://www.aeaweb.org/annual_mtg_papers/2005/0107_1430_

0901.pdf.

Boyer, E. Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate , Princeton:

Princeton University Press, 1990.

The Gwenna Moss Teaching & Learning Centre, “What is a Teacher Scholar?”

Symposium Proceedings , University of Saskatchewan, 2001.

Whitehead, A. N. Aims of Education . New York: The Free Press, 1929/1957.

Whitehead, A. N. Process and Reality: Corrected Edition . New York: The Free

Press, 1929/1978.

Whitehead, A. N. Essays in Science and Philosophy , New York: Philosophical

Library, 1948.

Check out our website www.usask.ca/tlc to read a more detailed version of this paper by Adam Scarfe.

While I have here briefly analyzed

Whitehead’s outline of how teaching informs research, it must be affirmed that teaching also has intrinsic value, beyond its instrumental value it has in the benefits that it brings to research.

It would be a mistake to suggest that teaching only has value in terms of some static notion of research or that good researchers are intrinsically good teachers. Overall, in his philosophy of education, teaching and research form what he calls a ‘logical contrast’, meaning that certain concepts that are said to be ‘opposed’, actually stand together in their mutual dependence and symmetrical requirement ( Process ,

348). In short, for him, research informs teaching and teaching informs research equally and co-dependently.

And, like Ernest Boyer’s Scholarship

Reconsidered , Whitehead frames this logical contrast between research and teaching through the notion of

‘scholarship’ ( Aims , 99-100).

T

HE

GMTLC

C

ONGRATULATES

D

R

. E

RNIE

W

ALKER

,

D

EPARTMENT OF

A

RCHAEOLOGY

,

C

OLLEGE OF

A

RTS

& S

CIENCE

S

PRING

2005

M

ASTER

T

EACHER

A

WARD

R

ECIPIENT

T

TT

TT

T

The University of

Saskatchewan recognises that teaching is one of its primary functions and, accordingly, it expects its faculty members to strive towards excellence in their instructional responsibilities. Faculty must seek constantly to improve their teaching so our students are given as rich and satisfying an educational experience as possible. The Master Teacher award, created in 1984, recognizes and celebrates excellence in college teaching.

For more information on teaching awards go to www.

usask.ca/tlc.

12

S

TEAM

,

S

AUTEE

,

AND

F

RICASSEE

:

L

EARNING TO

C

REATE AND

B

ENEFIT

F

ROM

I

NCLUSIVE

L

EARNING

E

NVIRONMENTS

techniques (teaching methods), and be receptive to new flavours ( incorporating and employing , not just identifying , perspectives and knowledge other than our own).

I met with Deirdre Bonnycastle, a faculty member with the

Instructional Design Group of the Extension Division, who works with instructors to help them improve their online course. She started her teaching career with Aboriginal people, teaching in northern communities, then in Aboriginal urban settings ( for twenty years) and eventually became coordinator of equity services for Woodland campus of

SIAST, an experience that taught her “a lot about what needs to happen within an educational setting to improve opportunities for all the people.”

I asked her, “What are the top behaviours a teacher can work toward to ensure that (s)he has an inclusive classroom?”

She began by suggesting that we examine the word “inclusive” and that we ask ourselves “what does inclusive mean?”

“It’s both the perception of the student and other people in the class that this person is included and also a respect for differences. You’ve got to have both of those. You’ve got to have a sense that ‘I am part of this class’ and ‘it’s normal for me to be part of this class’ and ‘it’s normal to have different perspectives.’ And you do that in a variety of ways.”

By Tereigh Ewert-Bauer, GMTLC

Imagine

that the only cooking skill you have is boiling (which will require less imagination from some readers than others), that the only foods you choose to cook are chicken, potatoes, and cabbage, and that the only seasonings you chose to use are salt and pepper. How interesting, appealing, and nourishing will your meals be?

How many times do you think that guests would return to your home for dinner parties? How long do you think you will enjoy working with these same foods in the same ways?

March 21 st marked yet another “International Day for the

Elimination of Racial Discrimination” campaign, a day that prompts us to engage in anti-racist activism and to find ways to eliminate racism from our culture. As teachers, regardless of discipline, we have two remarkable opportunities. The first is to create truly inclusive learning environments, and the second is to broaden not only the minds, experience, and knowledge of our students, but also our own, as teachers.

Often, when we speak of “diversity” in the classroom, we talk about “recognizing” and “celebrating” our differences, but inclusive learning environments demand that we move beyond mere “recognition” and “celebration” of difference to the difficult, risky work of interrogating often systemic racism in our teaching practice, in our curricula, and our institution.

Creating an inclusive classroom is not unlike broadening one’s culinary repertoire. We must experiment with new ingredients (content, knowledge), explore new cooking

13

Bonnycastle’s Suggestions for Creating an Inclusive

Classroom Environment

1. Include the perspective[s] of other groups in your course content [including images].

“When you have images for your marketing for your university or your course or your department, who are you marketing to?” A university may be “notorious for not including

Aboriginal people in their marketing material unless it is for an Aboriginal program, or if they have images of Aboriginal people, they are in traditional dance-type costumes. They’re the ‘entertainment,’ they’re not students.” Students have to be able to see themselves as belonging in your class.

2. Ensure that students feel not only that they belong in your class, but also that they belong in the discipline e.g. including literature by Aboriginals in a Canadian literature class. Inclusion in the UID guidelines is not a general term referring to how you make courses more accessible to a variety of students. Inclusion in the guidelines means examining how different cultures, races, classes, genders and abilities are represented (or aren’t) in your curriculum (representation includes images, text, sound, multimedia etc.).

3. Present your curriculum in a variety of ways

(most commonly called ‘multimodal’).

“We know that your discipline doesn’t just exist in writing...[but] we have a tendency in university that that’s the only way we present information, is in a written form, and we’re missing so much...in what is really going on in science if we assume

that that’s the only way that knowledge exists. One way of capturing other forms of knowledge is to respect the perspectives of people from other areas. They add to the knowledge in your discipline, they can add to the knowledge that other students find out about your discipline, so when

I talk about ‘difference’, I talk about a way of improving knowledge, rather than an add-on. One of the ways of doing that is using more active learning and project-based learning in your classroom because people will bring their perspectives to those situations.”

4. Employ multimodal assessment so that “students have the opportunity to show you what their strengths are.”

One tool for this might be the use of a learning portfolio.

5. Make our courses, materials, and teaching accessible.

“We need to be aware of how students access knowledge, what are their expectations of teachers, [because] cultural expectations might be different.”

6. Deliver your classes at the appropriate level; don’t deliver your classes at a PhD level when your students are undergraduates.

Part of this involves making sure that we are teaching at the right level, but it also involves not just using but teaching the language

(and jargon) of our discipline, thereby equipping our students with the tools they need to succeed in the discipline.

7. Provide feedback that is very concrete —what is it that they are doing well and what is it that they need improvement in? Too many instructors are too vague in their feedback, when they really need to be specific about the core requirements about that class.

Well-constructed rubrics are very useful because they can give the students a better sense of what it is that is expected of them. Additionally, samples of assignments (essays, lab reports) that illustrate “this is what an ‘A’ looks like, this is what a ‘C’ looks like” etc, are concrete ways to communicate your expectations to your students.

8. Make genuine contact with your students. Some students may appreciate having the opportunity to talk about their personal experience, their culture or their place of origin, but to do this, first, there must be a rapport between teacher and student, the classroom must be a place of safety and respect for all present, and the student must never feel that (s)he is being asked to represent an entire group of people.

I then asked, “What are some of the teaching behaviours or assumptions that we are mostly likely to make without realizing that they are undoing our attempts to create an inclusive classroom?” and Bonnycastle cautioned:

1. We make the assumption that our teaching style is universal.

In many cultures, learning is much more reflective, whereas in a mainstream

Canadian teaching environment, we encourage our students to be more impulsive, quick on the draw, with rapid answers which for whatever reason, is viewed as a sign of intelligence. Ask yourself: “How does your teaching style result in certain expectations?”

2. We lecture and expect that the lecture is enough, that just by listening to the teacher’s voice, the students have understood everything that was presented in the lecture.

Content must be presented in alternate formats, giving students an opportunity to revisit material, and to reflect on that material.

This is especially important when giving instructions or procedures.

3. We either blatantly or subtly, intentionally or unintentionally, make fun of, or humiliate students.

Not only does this make the student feel uncomfortable and like (s)he is not part of the class, but it also sends a message to the other students.

4. We often don’t have a clear sense of who we are (or where we are coming from) as teachers.

“Of course, we prefer our own teaching and learning style, but we also have to realize that that means we are leaving out other people [who do not teach or learn in the same ways].”

5. We need to make connections.

A recent study indicates that the majority of professors are abstract learners, while the majority of undergraduate learners are concrete learners. Bonnycastle says,

“It’s like they are talking two different languages.” The professors often fail to provide opportunities, or to help the students make connections between the abstract and the concrete.

As we spoke about the campus-wide need to create inclusive learning environments, I ventured, “I think that a lot of tired and overworked faculty might say, ‘What you are proposing [these steps to creating an inclusive classroom] is more work than I can handle.’”

Bonnycastle replied, “Yes, it does take time to develop a truly [inclusive] classroom, but little pieces build on little pieces over time. [Mark Chessler says] ‘The effort to move toward just and effective teaching, to create a multicultural classroom, is hard work, requiring considerable time and energy.

It is lifework: It will happen not in a day or a semester but over a lifetime of conscious effort to unlearn and learn.’”

Like learning how to cook in new ways and with new ingredients, learning to become a more inclusive instructor initially requires hard work, the

“unlearning” of former teaching habits, and sometimes even some “cooking lessons.” Over time, however, you become more proficient with your new skills and approaches, and soon they become second nature. To facilitate this evolution, Bonnycastle has created a diversity group on PAWS, where instructors may access links relevant to issues of diversity in education, and where they may discuss and exhange ideas. Either look in the PAWS groups or contact

Deirdre Bonnycastle directly to find out how to join the group

(966.1803).

14

S

PRING

West, GMTLC

T

EACHING

D

AYS

How Community Affects Teaching,

Monday, May 9, 1:30 – 3:00 PM,

Tereigh Ewert-Bauer and , Kim

to enhance the teaching and learning exchange. These strategies can be ‘adapted not adopted’ to meet the needs of specific learners and classroom content. Participants in the session will be involved in activities that will demonstrate ways to connect with learners.

In the class “GSR 989:Introduction to University Teaching,” we have discovered the incredible importance of our classroom community and how it can create a successful cooperative learning experience. Community in the classroom will be discussed as a process that is both the instructor’s and the student’s responsibility. In this workshop, participants will explore how their classroom communities can enhance and even challenge their roles as ”teachers.”

Scholarly Teaching: The Net and the Haul, Wednesday, May 11,

9:30 – 12:00 AM. Repeated 1:30

– 4:00PM, Eileen M. Herteis,

Director, Purdy Crawford Teaching

Centre, Mount Allison University,

Sackville, NB

Magic Mud and Metaphors: Using a diversity of instructional strategies in the classroom,Tuesday, May

10, ,1:30 – 3:00 PM, Sandra

Bassendowski, Assistant Professor,

College of Nursing

Our contemporary classrooms reflect a diversity of learners with unique characteristics related to ethnicity, age, literacy, health status, educational level, learning abilities, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, and degrees of motivation. How do educators meet the needs of these diverse populations and present content in a way that connects with the learners? Educators need to talk to each other about the following questions- “What impact is this instructional strategy having on student learning?” If an instructional strategy is not having an impact on student learning- is it worth having as a strategy? Using a framework of thinking-learning-teaching, the presentation will discuss a variety of instructional strategies that can be used

What is the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning? And how do we document that scholarship convincingly in a teaching portfolio? Too often, we use the term “scholarly work” to refer only to our research, diminishing the importance of our other academic responsibilities, most specifically teaching and service. Furthermore, when we say “research,” is it code for the product: publication in peerreviewed journals? Do we also value the process: discovery, the acquisition of new knowledge that will enliven and inform our teaching and benefiting our students, but which may never appear in an article or conference presentation?

Referring to two web sites, which she developed while working at The

Gwenna Moss Teaching & Learning

Centre, Eileen Herteis will guide participants through the process of exploring their own scholarship of teaching, in all of its facets, and documenting it in a portfolio.

This event is funded by TEL.

“TEL All” Showcase - of Exemplary

TEL Projects, Thursday, May 12,

4:00 - 5:30 PM

Several computers will be set up in the

GMTLC demonstrating exemplary TEL projects currently being offered at the

U of S. Subject Matter Experts and their project teams will be on hand to

“TEL All” about their TEL experience and answer any of your questions.

We hope you will take a few minutes to enjoy some wine and cheese and take advantage of this opportunity to network with colleagues. Hosted by The

Gwenna Moss Teaching & Learning

Centre and TEL. For further information, contact Sheena Rowan, TEL Project

Manager 966-1487.

Electronic Portfolios: Implications for University Learning and

Teaching, Tuesday, May 31, 1:00

- 4:00 PM, Angie Wong, Director,

Centre for Distributed Learning

Portfolios have features that can make them powerful and versatile tools for learning and assessment, including the facilitation of reflective practice, selfassessment, and self-directed learning.

E-portfolios, with the added value of technology to present and store multiple examples of a range of work, allow students and faculty to showcase their progress and growth over time. This workshop will begin with a summary of the basic premises about assessment and learning that portfolios can help to illuminate. Examples of application among three user groups will be provided. The three groups include undergraduates engaged in experiential learning, mid-career adults engaged in continuing professional education, and faculty engaged in development teaching portfolios.

Participants will engage in a discussion of the benefits and limitations of e-portfolios within their contexts of university learning and teaching.

15

P

G

,

RADUATE

S

TUDENTS

&

The GMTLC’s Joel Deshaye recently interviewed Professor Peter

Stoicheff, the inaugural winner of the Distinguished Supervisor Award

(2002), for his views on relationships between professors and graduate students. As a graduate student in the English department from 1999 until 2001, Joel worked with Dr.

Stoicheff to expand the collaborative hypertext projects that

Dr. Stoicheff initiated with other graduate students in past years.

They continue to work together on a hypertext research project.

JD To what extent can professors and graduate students be colleagues?

graduate students, who might enroll in the same instructional development programs (e.g. at the GMTLC)?

PS There’s always something to learn about one’s own teaching. I learn a lot by being a mentor for a highschool teacher at Joe Duquette school in the city. You see someone else teach a class and you always learn something.

Sometimes you’re learning what not to do, of course, but mostly you get ideas about good teaching from everywhere. So, I don’t see a problem with a comfort level involving grad students and profs learning about teaching together. To add to this idea, most profs teach in a kind of vacuum

-- they don’t get a lot of feedback from their own students or from colleagues

-- some, but not a lot. So any forum that brings people together who teach, regardless of their level of experience or their rank in the university, would be a good thing.

PS It’s always a fluctuating relationship

-- at times the supervisor is learning from the grad student, and at times the grad student is learning from the supervisor. At times they’re on equal footing regarding what each brings to a project. They can be colleagues in the sense that each brings a set of experiences and knowledge to a project, and in the sense that they can co-author papers and co-present at conferences. On the other hand,

I would suspect that a grad student would feel somewhat disappointed if, in most cases, he or she could not count on regarding the supervisor as a mentor who can lead the grad student through the professional and sholarly complexities of a research project by example. That is, the supervisor still must have the capacity to supervise, always, and not just be a research partner.

JD How can professors be comfortable learning about their own teaching in the presence of

JD We know that graduate students, with less experience and knowledge, can learn a lot, and learn deeply, from their professors. In what cases can professors learn from graduate students?

PS If you mean learning in the sense of learning about how to teach, then there’s a lot to learn from grad students.

For one thing, I have found, watching grad students teach, that regardless of occasional imprecision with the material, let’s say, they bring a freshness to the classroom that I try to learn how to emulate. At times I get too close to the material and strive for factual or informational precision over the other, less quantifiable ingredients of successful teaching. I get too hung up at times trying to communicate every nuance

16 of everything I know about a subject.

It’s interesting to watch someone,who’s newer to a field, deliver the information with a vitality that carries the material along with it.

JD I often hear of professors who employ their graduate students to do very mundane tasks in the office or in the lab: screening e-mail, data entry, cleaning equipment. Should this sort of situation be encouraged, or can it be avoided?

PS Sure, it can easily be avoided.

There are some mundane tasks that grad students can learn from -- everyone has to do them at some point -- it’s part of an apprenticeship. But, really,

I think grad students can be part of a research program in a genuine way that benefits the grad student as well as the supervisor. For instance, in the SSHRC world, we are now being encouraged to think in terms of longrange “programs of research” instead of discrete projects such as a book or set of articles. That’s a difficult transition for many of us, but it is a window of opportunity for working meaningfully with grad students. Instead of thinking,

“I’ve got to complete the following book, written under my name, and I need someone to check facts or compile an index or whatever” I can think in terms of “how can I isolate a particular problem or question or project within this larger program of research that an interested grad student can work on, that will become the student’s thesis or dissertation and will also become a contribution to my work?” That’s a shift in how we tend to do things in the humanities, for instance, but the sciences and social sciences have been able to do it to the advantage of the grad student for a long time now, so it can work.

JD When should professors and graduate students not interact?

PS I can’t think of an example of when they shouldn’t, though I do know that

I find it unpalatable when profs share their negative opinions about other colleagues or about administration or indeed about other students with their grad students.

JD How is interdisciplinary collaboration changing universities?

PS Enormously, and advantageously.

In essence in two ways: 1. interdisciplinary collaboration encourages all researchers and teachers to see what they do from a different perspective -- whenever you do that, new things happen; 2. it always puts pressure on researchers and teachers to ask the “so what?” question about what they do. If you stay politely protected within your own field, you tend to ask safe questions whose value is unquestioned by colleagues. If you move outside your own field, you are engaging with a group of people who ask you to explain and defend the value of what you’re doing. Sometimes that shuts you down, admittedly, and it’s not pleasant -- at other times, though, it strengthens and clarifies the work you’re doing and allows you to move it beyond the strictly academic into a larger sphere of relevance.

The GMTLC’s Joel Deshaye also recently interviewed Dr. Larry Sackney from

Educational Administration for his views on collaboration between professors and graduate students. Dr. Sackney is winner of the 2004

Distinguished Supervisor

Award at the University of Saskatchewan.

JD To what extent can professor and graduate students be colleagues?

LS It depends on the graduate student and the professor. If we believe in constructivism, then those relationships are possible. I try to deal with my doctoral students as if they were colleagues. In fact, I continue to engage in research and writing with former doctoral students.

JD How can professors be comfortable learning about their own teaching in the presence of graduate students, who might enroll in the same instructional development programs?

LS My current research is centered on learning communities and knowledge management; I therefore believe that we are all learners and can learn from anyone. Learning is not something we hide from others. Graduate students can help us to better understand our sensemaking and models of teaching.

After all, who best knows how our teaching is working for them.

JD What’s the most constructive role for a professor in a supervisory relationship with a graduate student?

LS For me, the supervisory relationship has to be one of mentor. I see my role being one of helping him/her to clarify the purpose of the research, the conceptualization, the research design and data analyses, and the study execution phases. Ultimately, my role is to make the graduate student a reflective learner that can solve his/her own problems and who feels competent to engage in his/her own research. This means providing support, encouragement, and a sense of direction. It is also important that I be available to the student and responsive to his/her needs in an appropriate amount of time. I think there is nothing worse than for a graduate student to submit work to the supervisor that sits on the supervisor’s desk for an inordinate amount of time.

JD We know that graduate students, with less experience and knowledge, can learn a lot, and learn deeply, from their professors. In what cases can professor learn from graduate students?

LS For me, this is a redundant question. I learn from my students continually by the questions they ask, by their reflections and interpretation of data, and by their insights to other constructs. If we do not learn from our students, we are not really learners and in knowledge work we all have to be learners.