Bridges Welcome, and Happy New Year!

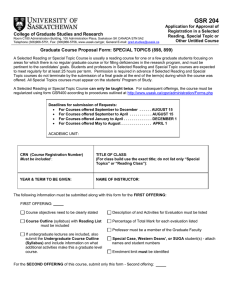

advertisement